Study: Employees intervene in only 2 of 5 observed unsafe acts

Survey respondents say they often choose not to intervene because they do not believe they can do so effectively

By Ron D. Ragain, Phillip Ragain, Mike Allen & Michael Allen, The RAD Group

When the employees in your company observe an unsafe action, what do they do? Do they document it? Do they stop it? Do they try to change the unsafe behavior then and there? Many companies have implemented observation programs as part of their overall safety management systems with the hope that such programs will make it easier to recognize and redirect the unsafe behaviors that occur within their operations.

These observation programs generally function the same way: look for and identify unsafe behaviors that need to be changed, then follow a procedure for helping to change those behaviors. This procedure usually involves filling out an observation card; at most companies, it also involves talking directly with the person committing the unsafe act.

Since the widespread introduction of observation programs in the drilling industry, we have come across a common concern among managers and safety personnel: Although employees are good at documenting the unsafe behaviors that they observe, they are not as good at directly intervening in those unsafe behaviors. They are not stopping and effectively changing unsafe behavior when it occurs.

When you consider that employees observe more than three unsafe acts a week on average – and 12% of employees observe more than five unsafe acts each week – this is a legitimate concern.

Incident investigation reports reveal an unsettling fact: Leading up to a significant number of incidents, someone observed something that they knew was unsafe but didn’t say anything. In other words, a significant number of injuries, environmental disasters and fatalities could have been prevented by direct interventions.

With this in mind, The RAD Group undertook an international, cross-industry study in 2010 to learn about direct interventions. We wanted to know if employees were intervening in the unsafe acts that they observed, and if not, why not? We wanted to know how effectively employees were intervening. When they did speak up, did they succeed in changing the unsafe behavior?

More than 2,600 employees in 14 countries were surveyed, and two-thirds of respondents were from the oil and gas services industry. The survey was conducted online in 10 languages, sampling a representative cross-section of operations, from roustabouts to chief operating officers.

Two specific items were evaluated: frequency and effectiveness of direct interventions. We wanted to know how often and how well people directly intervened in unsafe behaviors that they observed.

Before reading on, you might find it interesting to make a prediction. Drawing from your experience, how frequently do people directly intervene in the unsafe behaviors that they observe? When they do intervene, what percentage of the time do they succeed at changing those unsafe behaviors? You might be surprised by what employees around the world had to say.

Intervention Frequency

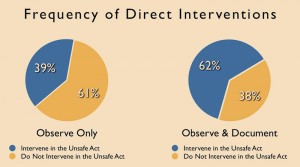

The study looked at frequency from two angles. First, how frequently employees intervene in the unsafe acts that they observe. Second, how frequently employees intervene in the unsafe acts that they observe and document as part of their company’s safety observation program.

It was found that employees observe an average of three unsafe acts each week, and they directly intervene in an average of 1.2 unsafe acts per week. This means that employees directly intervene in about two out of every five (39%) of the unsafe acts that they observe on the job.

On how frequently they directly intervene in the unsafe acts that they observe and document as part of their company’s observation program, respondents said that, on average, they directly intervene in three of five (62%) unsafe acts that they both observe and document.

When considered together, these two sets of results indicate that employees are more likely to intervene in the unsafe acts that they observe and document as part of their company’s formal observation program; however, whether they are documented, the percentage of unsafe acts that are not immediately stopped and redirected is high.

Respondents were also asked why they might choose not to intervene when they see someone doing something that they know is unsafe. A quarter of the respondents (25.3%) said when they choose not to intervene in an unsafe act, it is because the other person would become angry or defensive, and a fifth (19.3%) said that it is because it would not make a difference in the person’s behavior. In other words, respondents told us that they choose not to intervene because they do not believe they can do so effectively.

Intervention Effectiveness

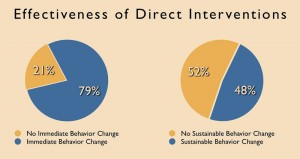

Two key indicators were examined to assess the effectiveness of interventions: what percentage of people immediately changed their unsafe behavior, and what percentage of people sustainably changed their unsafe behavior as the result of a direct intervention. “Sustainable” behavior change means that the person’s behavior change persists after the initial unsafe act without any further interventions.

Respondents said that four of five interventions result in immediate behavior change, which means they are 79% effective at producing short-term behavior change. We found this number to be surprisingly low.

As you might expect, employees are less effective when it comes to changing others’ behavior sustainably. Respondents said that one of two interventions results in sustainable behavior change. That is, employees are 48% effective at producing long-term behavior change. This number was predictably low.

Respondents were then asked questions on why they sometimes fail to change others’ unsafe behavior, and the answers showed that there are at least two significant reasons. First, the interventions are conducted in a manner that produces resistance. Respondents said that others react defensively in one out of every four interventions (27%), and they react angrily in one out of every six interventions (16%).

The second reason that employees frequently fail to produce immediate and sustainable behavior change is that they appear to address the wrong underlying causes of the unsafe behavior. Four out of five respondents (82%) said that when others act unsafely, it is usually because they do not want to make the extra effort to do the job the safe way. However, when asked separately about themselves, less than one of 10 respondents (8%) said that when they act unsafely, it is usually because they do not want to make the extra effort.

Respondents indicated that when they themselves act unsafely, it is usually because they either are unaware that the behavior is unsafe or because someone else is rushing them. This suggests that people approach safety interventions with a fundamentally false assumption. They tend to assume that the unsafe action is the result of poor personal motivation – laziness.

As such, not only is the intervention unlikely to produce sustainable behavior change because it targets the wrong underlying cause of unsafe behavior, but it is also likely to make the other person defensive or even angry.

The data described here demonstrates what we believe to be a significant challenge that must be overcome. Cumulatively, the results of the survey indicate that, on average, employees immediately stop only one-third (32%) and sustainably change only one-fifth (20%) of all of the unsafe acts that they observe.

While the numbers are slightly better within the context of formal observation programs – employees immediately stop half (49%) and sustainably change one-third (30%) of the unsafe behaviors that they observe and document – the data are nonetheless troubling. Put plainly, a significant number unsafe actions go unchecked and unchanged because employees either aren’t intervening or aren’t intervening well.

This article is based on a presentation at the 2011 IADC Health, Safety, Environment and Training Conference & Exhibition, 1-2 February, Houston.

In my experience, when you intervene (and I have) you jeopardize your job security. Managers get upset and embarrassed that they have to address the situation, and label you as a troublemaker. Executives officially say that they support safety, but in reality they don’t want to spend the money. So you’re labeled as an irritation.

I had stellar job performance reviews for years, and had recently won incentive and beyond-duty awards, when I pointed out that we had an unsafe condition. My bosses looked at it and deemed it acceptable. Later during a plant inspection an OSHA representative saw the same problem and asked me (among others) about it. I didn’t lie to the man. OSHA forced that company to look into and correct the problem, and my bosses got reprimanded. My bosses made our lives miserable as revenge. The executives used this incident as incentive for a safety campaign. They sent people out to interview us about our thoughts for improvements. I offered a couple of suggestions. About a week later I happened to be in an elevator with one of those executives (one who had made a big show about promoting the safety campaign) who snidely remarked that my suggestions were going to cost money and that made him look bad. About a month later I was given an early performance review, where I was deemed unsuitable and I was laid off. (Several others got the same treatment.) Now not only do I have to find another job, but my former company is giving me a bad reference.

I am still proud that I stood up for safety improvements, and nobody actually got hurt. I have no respect for my former bosses or that company, so I’m glad I’m out of there. But this is not the way it’s supposed to work, is it?

Ferd,

I’m sorry to hear about your situation. There are several aspects that go into an effective safety culture, leadership buy-in being one of the more important. They must first understand that a multitude of contextual factors go into changing an unsafe act or condition. They must have a population that is willing, and more importantly able, to have quality interventions to uncover the factors of unsafe conditions before they can ever gather the information and effect change. Once the front line employees provide them that information they must be willing and able to correct those factors before the behavior and conditions can be sustainably changed.

The reason I said that the population must be able to properly intervene is because many times leadership sees employees identifying problems, rather than solutions, to be an attack on their job performance. In hindsight, that is far from the truth, but done incorrectly will put the leadership on the defensive and can be counterproductive.

A quality intervention stops the unsafe act, identifies the critical factors that allowed that behavior or condition to exist, and then some sort of personal, group, or organizational fix to be made. If leadership doesn’t understand the principles of what drives failure, and the intervention (with leadership) is done in a way that breeds defensiveness, failure in the entire system, and that relationship, is inevitable.