Safe lifting initiatives focus on awareness, drops prevention

Companies work to enhance communication, empowerment, ensure procedures always followed

By Katherine Scott, editorial coordinator

Bishop Lifting Products, for example, focuses on aftermarket training for products, such as the MaxiRider personnel hoist, to ensure crews know how to properly handle lifting equipment.

Rig operations both onshore and offshore call for detailed safety procedures for management of equipment, specifically in regards to crane lifts, mechanical handling and dropped objects. For industry to continue toward safer lifts and reduce the associated injuries, communication with rig crews and equipment operators, as well as continuous assessments of crew competency, are necessary.

Lifting and handling safety can be looked at from two perspectives: personnel and mechanical. From the personnel aspect, company awareness, training, individual ownership and worldwide industry involvement all must be taken into account.

From the mechanical side, inspection procedures, safer equipment and proactive rig designs are cited by industry experts in their approaches to improving safety.

Dropped Objects

Dropped objects can cause fatalities, but with increased awareness, incidents can be avoided.

“We have some evidence that when it goes wrong, it can cause fatalities. At Shell, we talk about high-potential incidents (HIPOs),” said Gordon Graham, vice president of wells HSE for Shell. A dropped-object HIPO is something that falls but doesn’t cause a fatality but still with the potential to hurt someone, he explained. “And we still have too many of those high-potential incidents in our business.”

Investigation of the dropped-object HIPOs has helped Shell reduce the number of such incidents “We investigate it so that we get to the proper root causes,” Mr Graham said.

Lesson Sharing

One of the most effective ways to improve lifting safety is to create awareness of risks and to share lessons learned from actual incidents to prevent them from happening again. “There are pre-lift meetings, pre-tower meetings. There are meetings throughout the day on exactly what has to be done, so communication and awareness is the biggest factor of trying to reduce a lot of this,” said Andy Schott, senior mechanical supervisor – deck cranes for Diamond Offshore Drilling.

At Diamond, all post-incident findings are disseminated throughout the company. “We have robust investigation procedures where we look closely at incidents and near-misses. Findings are captured, and lessons learned are turned into HSE and technical alerts to help reduce incidents for future operations,” Daniel Ziglar, Diamond HSE supervisor-international, said.

In the US, what constitutes an “incident” and when it needs to be reported is defined by regulatory authorities in the US Code of Federal Regulations. “Not all incidents involve injuries, so incidents could be, you merely snag something or you hit something or you nudge something,” said Allen Verret, executive director of the Offshore Operations Committee. “Incidents provide us with a method of identifying acts that occur incidental to a lifting operation.”

The API Offshore Lifting Safety Data Workgroup (OLSDW), on which Mr Verret has been a member since its inception in 2009, is recommending to BSEE a more structured US Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) reporting document that provides more in-depth details on the incident that occurred (see Page 122).

Awareness also means helping crews learn how to spot dropped-object risks. “As you become more aware of what a dropped object is, you get more reports about near-misses that happen. The key to preventing dropped objects is to make sure that the near-misses are captured,” said Weng Fei Leong, HSE director-Asia Pacific for Baker Hughes.

Mr Schott said that keeping awareness at a high level with better job planning and daily meetings has helped the company lower its incidence rate. “It doesn’t do any good to have (a stack of paperwork) if the individuals aren’t daily made aware of the safety aspects of the lift.”

Further, Diamond initiated a hands-off lifting policy a year ago to remove people from potential risks. “I can say that injuries from lifting incidents, specifically to the hands and fingers, have taken about a 30% reduction, and that’s because of the hands-off approach,” Mr Ziglar said.

Role of Training

Increasing drilling activity around the world and the ongoing Big Crew Change also mean there are numerous new-hires in the industry – people who have little to no experience with lifting safety – as well as a lot of turnover. “You train a crew on how to use our MaxiRider, for instance, and within six months you might have a whole new crew. All of a sudden, you’ve got these guys that have a piece of equipment that’s picking them up in the air who have no training,” said Jeff Bishop, president of Bishop Lifting Products, which provides products and services for rigging and crane applications, such as the MaxiRider personnel hoist. The company believes that aftermarket training is key to ensuring safety in the use of lifting equipment. “Re-training is what we’re really focused on.”

Training not only shows employees the correct way to use certain pieces of equipment, it also provides companies the chance to gauge worker competency. Diamond Offshore uses its in-house lifting classes to evaluate the competency of their crane operators and deck coordinators, said Brian Maness, manager – global training systems integration. This allows the company to decide if the employee is still competent for his or her position, which Mr Maness said is “one of the advantages of having in-house schools.”

Further, training can be a stepping stone for crew members to make safety decisions on the rig. The OLSDW finds that a majority of offshore lifting-related incidents involved behavioral issues, Mr Verret said. Although changing an individual’s behavior is a complex undertaking, he believes that more hands-on training followed by testing of an individual’s retention does affect how the individual acts on the job.

While the human element in safety is often cited as the harder one to master, the equipment side can’t be overlooked either. At Diamond, not only do crews treat API’s RP 2D equipment inspection standard as a “bible” to live by, they’ve gone beyond it by adding items to the inspection procedures, such as dual-signature requirements, based on crane maintenance history and recorded incidents.

“When you go on tower as an operator, you inspect the crane with the previous operator. You sign for the crane in the condition it is in; the previous operator signs off stating the crane is in good operating condition with no physical damage. This happens every tower change of the operators. With this practice, the extent of downtime repairs and unnoticed problems have been reduced,” Mr Schott stated.

“API RP 2D is the document that best addresses some of the issues in the incident arena,” Mr Verret said. The current, sixth edition of RP 2D is being revised by the API Safe Lifting Committee to take OLSDW’s findings into consideration (Page 122). The seventh edition will incorporate new sections that include suggestions on additional training procedures for the riggers, operators and inspections, as well as a section on lift planning that advises rigs crews to go over preparation tasks, which ensures safety is discussed before a lift.

To better streamline rig inspections, Maersk Drilling Service’s David Woodruff, HSE advisor for Maersk’s Brunei operations, says he prefers to use a rig-specific DROPPED Object Prevention Manual with lots of photos and only a minimum of words, especially in operating regions where English may not be the native language for the rig crews.

“If you generate a manual that is full of words, people tend not to read it. … I’m a firm believer that a picture is worth a thousand words. It shows people exactly what they have to look for,” he said, noting that Maersk’s training videos also are language-free. “They are animated, and they are extremely good. I’m really impressed with them, and we’ve found these are very beneficial training aids.”

Safer lifting can also be enhanced even when the rig is still in the shipyard. Mr Woodruff said Maersk is working directly with Keppel FELS during the construction of its three highly automated, harsh-environment jackups to build in lessons learned from the commissioning and operations of similar previous units. “There are so many things that (Maersk has) learned over the years that I would like to incorporate onto these rigs while they are being built in the shipyard,” Mr Woodruff said. “The easier you can make it for the guys that have to operate that rig, the better it is.”

Mr Leong agreed, noting that rigs should be built with enhanced dropped object prevention in mind by integrating field feedback into the design itself. “We want to make sure that the rigs are built to some extent to be drop-proof,” Mr Leong said. One simple change could be to paint signs on a piece of equipment instead of hanging signs on the equipment; simply because “metal signage placed at height may potentially drop,” he said.

Personnel Transfers

Transporting crews from boat to rig in offshore operations is another lifting-related task that requires specific safety devices. In 2006, Billy Pugh Co introduced the X-904, a personnel transfer basket that takes out the most common risks of an offshore personnel transfer. The major safety features of the X-904 are overhead protection, outer protection and man positioning/fall restraint, said Paul Liberato, Billy Pugh Co president.

Enhanced equipment features aside, however, Mr Liberato believes that the most important element to a safe lift is appropriate preparation before the transfer begins. “First of all, make sure that the crane operator, the OIM, and the boat captain are in agreement that it’s a safe operating envelope. Mix in a thorough JSA and conduct regular pre-lift meetings, and offshore crane transfer is an extremely safe method of getting people on and off of a rig. The offshore community has done a good job in years past, but things are getting better and better as our safety culture in reference to personnel transfer evolves.”

Equipment Advances

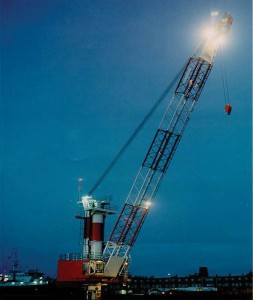

Staying current with equipment design and technology advances is also important to reducing safety incidents. Mr Maness noted that Diamond has replaced all mechanical cranes and services with state-of-the-art hydraulics. The company is also using knuckle boom cranes to enhance safety on its new fleet of drillships. A knuckle boom crane has a boom hinged in the middle to minimize motion and increase control due to the reduced distance between the crane and the load being lifted. The knuckle boom crane is also more useful in narrow areas and smaller spaces, Mr Maness explained, and it makes loading and unloading that much easier, even when the site is full of obstacles. Diamond has four ultra-deepwater drillships under construction at the Hyundai yard in South Korea, with first delivery in June 2013 and one every six months after that.

Beyond awareness and training to enhance incident prevention, reducing lifting incidents also requires empowering employees with the authority to stop work if they see a potential risk. In recent years, industry has seen increased personal responsibility and accountability. “We do really emphasize stop work authority,” Mr Ziglar said.

Mr Maness added, “If anybody sees anything, and I don’t care if you’re the newest person on the crew or not even on the crew, you’re walking by, you call stop work.”

Mr Woodruff cited Maersk’s hazard identification program, which gives monetary awards for any “good, genuine” hazard elimination issues resolved by an individual. “These guys are encouraged to identify hazards and then not just identify the hazard and report it, but take ownership of it. If you see it, you own it.”

Although dropped objects has long been a topic of focus within the industry, especially in relation to lifting and handling safety, some believe that this topic deserves a new look and approach.

“I don’t think as an industry that we are consistent in talking about dropped objects,” Mr Leong said. Baker Hughes, for example, is addressing possible gaps in existing operational controls by drafting a document that looks at just dropped-objects risk. “Existing operational controls in a fall protection plan regarding specific activities, such as falls, which also broadly covers the potential of dropped objects when working at heights, will include more industry-standard details to prevent dropped objects. For example, the operational control on dropped-objects prevention will require use of tools with lanyards attached to personnel working at certain heights as an added control measure to prevent dropped objects,” he said.

In 2009, Shell started a Prevention of Dropped Objects campaign designed to eliminate dropped objects, prevent harm to people from dropped objects and prevent damage to equipment and assets from dropped objects. The campaign highlighted four principles: Contractors providing equipment and personnel on Shell well sites will have a dropped-object prevention plan; there will be a systematic dropped-object inspection program; there will be a worksite hazard management for dropped objects and; there will be audits to check for compliance with the dropped-object prevention plan. Mr Graham wrote a detailed article on Shell’s dropped object prevention campaign in the November/December 2010 issue of Drilling Contractor a year after the campaign launched.

One useful approach Maersk employs to reduce dropped-object incidents is red zones, which remove individuals from places on the drill floor where drops are most likely to happen. “That red zone on the drill floor is so that no one goes in there when the machinery is moving. If we’re drilling, if the pipe’s rotating or if we’re tripping in or out of the hole, if the drawworks are going up and down, nobody is in that red zone,” Mr Woodruff said.

Shell, too, has adopted red zones and has implemented no-go zones, both seen as effective mitigation techniques, Mr Graham said. A no-go zone requires a permit to enter an area, while the red zone requires verbal permission, he explained. “You’re basically controlling the area.”

Another approach may be elimination of equipment on the rigs that don’t necessarily need to be there. Mr Woodruff advocates addressing dropped objects by starting from the beginning – removing all equipment that serves no purpose and has the potential to become a dropped object. “Go right back to the root cause. I would like to see elimination of superfluous and redundant pieces of equipment, elimination of stuff that really doesn’t need to be there in the first place.”

The drill floor is typically where most drops happen, Mr Graham said. In and around the drill floor, “we’re doing a lot of lifting operations to get stuff into the well, so there’s equipment that’s moving, being lifted and hoisted.” Shell requires its crews to register their tools before going up the derrick and register them back in when they’ve come down, ensuring that nothing is left at height for the potential to fall, he said.

Looking at the overall state of drops safety, Mr Leong stressed that there must be worldwide industry involvement in the effort. “The key ingredient for success of drops safety within the industry is cooperation from the operator, the drilling contractor and service companies like Baker Hughes,” he said. Mr Leong serves as chairman of Dropped Object Prevention Scheme (DROPS) Asia Pacific, a regional chapter of the DROPS global workgroup, which is administered and facilitated by a global steering committee based in Aberdeen.

Regional chapters of DROPS arrange forums at self-determined intervals through the year. Members exchange best practices, present new techniques and discuss dropped-object prevention performance. These forums take a broader approach to eliminating incidents by including shipyards and their employees as well, Mr Woodruff said. “If people start to talk about it and transfer this information, then we’ve got a lot better chance of doing something to prevent it and hopefully save somebody’s life.”

Mr Graham suggested that all companies should implement a plan for the prevention of dropped objects. Additionally, he noted that keeping rig crews aware of dropped objects is necessary as the industry continues to grow. “It’s a continuous process of learning.”

“The industry in general has been very receptive to the efforts to communicate where the trends are,” Mr Verret said. He believes that industry will continue to address issues to reduce incidents as long as it is aware of current trends. Communication of industrywide incidents helps identify these trends, and communicating through trade associations, regulatory bodies and forums helps disseminate valuable lessons, he said.

Mr Ziglar also believes in industry cooperation, supporting the sharing of information across the industry through IADC. “IADC is kind of a center point for capturing industry-specific issues and incidents, so there is good learning potential and sharing through the organization.”

Mr Schott followed with a similar sentiment. “That’s what it’s all about, the actual sharing and communication between people. Even though we are competitors, it’s still out there because it’s based on safety.”

MaxiRider is a trademark of Bishop Lifting Products.

There is no such place on the rig floor where drops are most likely to happen. Something can fall from the Crown and end up at the end of the pipe deck.