Buoyed landing string among upgrades allowing Chevron to use 15k rig to drill 20k well

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

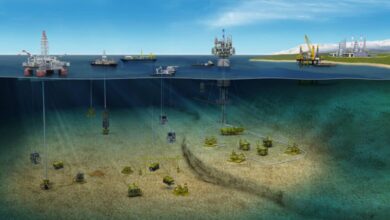

As operators look to deeper waters, longer and heavier casing strings have become more of a necessity. However, the mechanical requirements that result from the landing and cementing of these heavy casing strings can push the limits of current offshore rig equipment. In some cases, they require non-conventional alternatives to manage loads that may be outside of normal drilling envelopes of existing rigs.

To drill its first 20,000-psi deepwater development well in the US Gulf of Mexico (GOM), Chevron’s original plan had been to use a newbuild drillship equipped with a 20,000-psi blowout preventer (BOP), a 3 million lb/ft hookload, and a suite of new high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) equipment. However, in 2021, while that drillship was still under construction, the operator had an opportunity to deploy another available drillship in the area.

Using this drillship, Chevron was ultimately able to drill the 20,000-psi well to TD even though the rig only had a 15,000-psi BOP and a 2.5 million lb/ft hookload capacity, which were lower than the estimated capacities needed for safe drilling and casing operations. The project has provided Chevron with a blueprint to drill future wells using rigs outfitted with lower-rated BOPs, if needed, said Thomas Chase, Field Drilling Engineer at Chevron.

“We had to look into the possibility of pre-drilling the well, which would help us accelerate first oil on the project. But before we could do that, we had to see whether that well was feasible and what equipment or operational gaps we would need to address to enable safe drilling and casing running operations for the project,” Mr Chase said at the 2023 SPE/IADC International Drilling Conference. He and Aaron Garcia, Drilling and Completions Engineer at Bureau Veritas, discussed the equipment upgrades and the operational gaps that had to be addressed.

Equipment upgrades

Chevron opted to run 16-in. nested liner strings that were to be deployed deeper than any offset well the operator had designed before. Running these strings required rig equipment updates, such as to the shear-and-seal capability of the blind shear ram (BSR) and a buoyed landing string (BLS) to reduce hookload.

One of the first issues Chevron addressed was the need to use a production casing that was rated to withstand the HPHT environment and was large enough to house the completion equipment needed to deliver the target production rates in the well. The company determined that the ideal well configuration would use a deep-set, 16-in. nested liner string set approximately 5,500 ft deeper than the 16-in. setting depth on the nearest appraisal well. To push the liner that deep, the company used a heavy-duty landing string (HDLS) to provide the necessary tensile capacity.

“We needed a deep-set 16-in. liner in order to set our subsequent strings deeper, which would allow us to have the formation strength to maintain the worst-case discharge containment. However, pushing the liner that deep meant we were going to have to push the shoe deeper, and that means more casing is being run and a higher hookload. So, we knew we were going to have to run a heavy-duty landing string, as well,” Mr Chase said.

As Chevron investigated potential well trajectories, Mr Chase said it became clear that, even with a simplified well path, the anticipated hookload required to run the casing would exceed the hookload capacity of the rig and the associated casing landing equipment. So the company had to look at further mitigations to reduce the hookload.

One of those mitigations was an upgrade to the BSR. The shearing capability of the BOP stack for the contracted rig had a wall thickness limitation due to a fold-over pocket in the ram’s body design. As the HDLS needed to run the heavy-duty 16-in. liner, a BSR with a wall thickness greater than that of the rig’s blind shear ram was needed. A new BSR design was qualified that eliminated the fold-over pocket, thus removing the wall thickness limitation.

Chevron also made special considerations for the HDLS. Mr Chase said that, for most deepwater casing runs that require HDLS, it is common to inspect pipe to a minimum remaining body wall (RBW) to ensure that all points along the pipe body have the minimum required tensile capacity to withstand the casing running loads.

However, the normal pipe inspection process typically does not measure the maximum RBW along the pipe. Mr Chase said this is generally not an issue as the shear pressures are typically low enough to accommodate slight increases in shear pressures should the wall thickness be greater than the minimum RBW. However, for the 20,000-psi well, the shear pressures were already on the upper end of the OEM’s pressure rating, so any unexpected increase could be damaging.

To address this concern, Chevron worked with Bureau Veritas to run a series of shear calculations at varying RBW values to obtain the upper and lower limits for the shear pressure. The operator also worked with the drilling contractor and pipe inspection contractor to identify HDLS pipe that could withstand pressures within the determined range.

Chevron and Bureau Veritas also looked at the pup joints. Chevron opted to manufacture these joints from the same material as the tool joints of the landing string, but with a thicker tube body. Bureau Veritas verified that, with the thicker tube body and one-piece construction, the joints would be able to attain a 2.5 million lb/ft tensile capacity. “We wanted the pup joints to be one solid piece of material throughout, which is different from what we typically have with pup joints,” Mr Garcia said. “Also, with the joints having the thicker tube sections, they’re better suited for withstanding the required loads.”

The next step was to mitigate the hookload concerns for the 16-in. liner run. There were significant concerns, like with hole stability, with the two options considered – risk assessing the casing run as a one-way trip, and pumping out of hole if needed to pull the casing to surface. The 16-in. liner would have to be run through more than 10,000 ft of open hole, and as they were planning to push the 16-in. liner hole section deeper than it had for other nearby wells, the operator had limited offset well data for the hole section.

BLS equipment proved valuable. It consists of buoyancy modules that are attached to the landing string pipe body in segments. Mr Chase said these modules were critical in enabling casing running operations that would have otherwise exceeded rig capacity. “The buoyant force that these modules impart helps to reduce the landing string weight, which in turn allows for casing runs that would have not otherwise succeeded with existing rigs.”

To prepare for the BLS running operation, a rig trial was conducted during the between-well maintenance period, which allowed the rig to optimize both the handling procedure and module placement on the pipe. Because of the large-diameter modules installed on the pipe, special handling equipment was required to run the BLS. Ultimately, Mr Chase said these rig trials helped to minimize nonproductive time for the actual job.

The last equipment consideration was the top drive cement head. To increase its tensile capacity rating, the cement head was customized with a body connection that maintains constant tensile capability with the increase of internal pressure. This increased the tensile capacity rating from 2.25 million lb/ft to 2.5 million lb/ft.

The upgraded equipment allowed the rig to handle the well’s high pressures without exceeding its capacity. When Chevron ran the 16-in. liner with the BLS, the rig was able to achieve a hookload reduction of approximately 160,000 lb/ft, thereby safely running and cementing the 16-in. liner on depth. Mr Chase said the recorded hookload of 2,494 kips is the heaviest the company has ever recorded. DC

For more information, please see SPE/IADC 212545, “Designing and Qualifying Equipment for a Potential World-Record Deepwater Casing Landing Operation.”