Re-inventing subsea intervention to keep economics above water

By Katie Mazerov, contributing editor

Ten thousand feet below the platform, a well production tree, with all its pipes, manifolds and production lines, is signaling yet another new frontier in hydrocarbon recovery. Far above the surface, industry engineers are pushing the envelope on cutting-edge technologies and systems that will keep the well producing under water, but keep the economics above water.

While it is hardly a new concept, subsea intervention is being re-invented for the challenges presented by deep and complex offshore wells. Cutting-edge conveyance systems, state-of-the-art tools and innovative ways of using proven, conventional methods are being developed to transform what is often a cost-prohibitive and risky undertaking into a viable option for operators.

Subsea well intervention has been a reality for the industry for about 20 years, and intervention activities typically occur about five years after the installation of the production equipment, said John Griffin, sales and business manager, after market services, Western Region, for FMC Technologies. “Deepwater production really kicked off in the early 2000s, and we’re now seeing challenges emerge as the demand for deepwater interventions increases,” he noted.

The North Sea is not the deepest region in the world, but it does have some of the most severe weather conditions and the oldest and largest active base of subsea wells. This makes it the most mature and demanding market for subsea well interventions. But as operators increasingly grow their subsea infrastructure into deeper waters in other regions, there will be an incentive to advance existing technologies to these more challenging arenas. Among deepwater arenas, Brazil is the most mature, followed by the Gulf of Mexico and West Africa, Mr Griffin said.

“The major challenge in the future is translating the successes we’ve had in the shallower-water applications, such as the North Sea, to deeper waters,” he said. “There is a huge difference between reliably performing well interventions in 500 to 2,000 ft versus 10,000 ft.”

Managing the lines that deploy tools, guide equipment, provide electrical and hydraulic power, and convey chemicals is one of the key operational challenges, Mr Griffin explained. “We must be able to minimize the lines in the water or keep them untangled so that we can keep the operation on track.”

Most subsea well interventions today incorporate riser-based workover systems. The game-changers emerging for deepwater well intervention will be light-duty intervention risers and riserless light well intervention (RLWI) technology, which eliminates the need for the expensive drilling rigs required in conventional riser-based interventions. FMC’s RLWI system, which has been used successfully in the shallow regions of the North Sea, is deployed on cables from a boat and uses wireline to run the tools. With North Sea Alliance partners Island Offshore and Aker Solutions, FMC has successfully performed more than 140 RLWI operations in the North Sea. Light-duty intervention risers are smaller cousins of full-bore completion workover risers. Their lighter smaller-diameter riser string can simplify coiled-tubing deployment and macaroni-string circulation jobs from smaller, more cost-effective intervention vessels.

The company expects to enhance the system for the deepwater and ultra-deepwater markets. “The combination of ultra-deepwater and pressures of 15,000 psi is really going to push the envelope on this technology,” Mr Griffin said.

FMC’s Enhanced Vertical Deepwater Tree, a production tree designed for deepwater environments, has been optimized for deepwater interventions and can work with both riser-based and riserless methods, Mr Griffin said. The system is a monobore vertical tree with safety valves in the vertical bore. It is designed to be modular, so modules can be added and retrieved from the well based on the kind of well intervention selected.

Supplying large quantities of chemicals, adapting coiled tubing (CT) with subsea injector heads and hydrate control at the well’s stuffing box in deepwater environments are among the advances still needed to move the industry forward. “Versions of a composite, high-strength, neutral buoyant, cable and structure are being incorporated into designs that can effectively deploy and retrieve hardware and transmit electrical power and communications irrespective of water depth,” Mr Griffin said. “Wireline and e-line tools are capable of performing nearly 70% of intervention operations using riserless intervention. However, CT is still needed for more intensive through-tubing problems in wells, such as fluid circulation or fracking, hardware repair and minor sidetracking.”

Coiled tubing is typically run through a completion workover riser, where it is protected and supported by a riser pipe and a return circulation path. Light-duty intervention risers offer the same capability but from smaller vessels with smaller tension and volume capacities. “Longer term, we’ll need a CT design that can support itself to work in an open-water, riserless scenario from ever smaller vessels.”

As is often the case, the technologies will emerge as they become economically viable. “Operators lead the way in providing the needs,” Mr Griffin said. “We bring the tools and services to address their needs.”

Major North Sea operator Statoil is using RLWI vessels in the region for maintenance and operations to enhance production in older wells, said Øyvin Jensen, manager drilling and well intervention. “Operators are looking for systems that will provide the confidence they need to perform necessary maintenance work and interventions for continued production in the growing number of mature wells,” he said. “Looking ahead, I see potential in using RLWI for more cost-effective permanent plug and abandonment operations of subsea fields.”

He agrees that the big challenge for the industry going forward lies in adapting RLWI systems for the ultra-deep environments. “The demand is not there yet for Statoil, but the industry is pushing the technology in anticipation of that need,” he said.

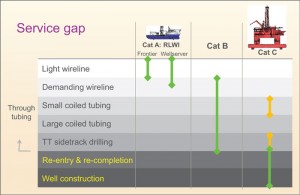

Statoil is in the process of designing a semisubmersible Category B well intervention rig that will be able to service most of Statoil’s current intervention needs for wells 1,000 ft and deeper. The rig will be designed to provide well intervention and light drilling with functions such as through-tubing rotary drilling (TTRD), wireline, coiled tubing and high-pressure pumping and cementing.

Aker Solutions will introduce its new deepwater intervention vessel, the Skandi Aker, in October, offering what the company believes will be a game-changer in deepwater subsea well intervention. The vessel is expected to be deployed in West Africa, a key deepwater market along with Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico.

The vessel marks the culmination of the company’s development of a business plan to provide cost-effective subsea well intervention solutions. “As far back as 2006, we began realizing the huge upcoming potential for subsea well intervention, with the increasing number of subsea wells in deeper and deeper waters. We did a lot of work to analyze what the market needed and discovered that subsea wells were being intervened much less frequently than platform wells,” said Frank Willumsen, business development manager, Aker Solutions.

The reason centered on the prohibitive cost of bringing in a drilling rig for a subsea well intervention. “With a strong need to replace dwindling resources, most oil companies found it more economical to use the scarce rig capacity for exploration and production drilling rather than to do interventions. As a result, production from existing subsea wells is 30% to 40% lower than from platform wells.

“The design does not really involve a lot of new technology, but rather brings together existing technology in new configurations into a vessel that is purposely built to perform safe and efficient well intervention services,” Mr Willumsen said. The key advantage is that it can provide the full scope of services without the need for a marine riser and thus replace an expensive drilling rig. “We wanted a solution that is cost effective for oil companies, one that would provide a customized platform for performing well interventions in deepwater from a monohull vessel,” Mr Willumsen said.

Well intervention has long been an important service offering from Aker Solutions, which performs downhole maintenance with wireline and coiled-tubing operations. Its expertise encompasses well control technology, including intervention workover systems allowing safe entry into a well through a subsea tree and quick disconnection in the event of an emergency.

As the centerpiece of the company’s well intervention services, the Skandi Aker offers a fully integrated solution through a 7 3/8-in. high-pressure riser. “With the exception of (Helix) Well Ops’ semi Q4000, the Skandi Aker is currently the only available alternative to using drilling rigs for complete well services,” Mr Willumsen said. The monohull vessel is the first classed as a MODU unit according to Det Norske Veritas’ (DNV) WELL notation. This means that the vessel can take hydrocarbons from the well on board and thus do well testing, well cleanup and flaring off hydrocarbons through a flare at the stern.

“In shallow water, such as is predominantly found in the North Sea, it’s possible to use open-water wireline to get from the surface down to the wellhead,” Mr Willumsen said. “But there is a limitation to how deep we can go using current riser-less technology. The Skandi Aker is all about conveyance,” he continued. “It offers a cost-effective way to bring the intervention services down to subsea wells 9,800 ft below the surface. We are striving to provide a turnkey solution, a fully integrated service where we come in with a unit that allows us to hook onto the well and then do the work. That will allow the operators to limit the operation to just one service provider rather than several.

The vessel is highly flexible and can also be used for subsea installation and construction work, which is particularly beneficial in remote areas where limited infrastructure can make it very expensive and cumbersome to mobilize several different units or equipment to perform various tasks,” Mr Willumsen said.

The Aker Wayfarer, a sister vessel of the Skandi Aker, is working as a construction vessel but may also be retrofitted for intervention work identical to the Skandi Aker, a process expected to take 18 to 20 months, Mr Willumsen said.

Alongside conveyance systems, advances are being made in the well intervention tools themselves to deliver greater reliability and efficiency.

Red Spider Technology, headquartered in the UK, provides subsea and completions solutions for operators in the North Sea and increasingly to international clients.

The company’s core technology, eRED, is a downhole computer-controlled valve that can be opened and closed by remote control. Developed in 2004 as an intervention tool to reduce wireline runs, the battery-controlled system has since been upgraded to operate as a completions and workover tool for reducing or eliminating interventions, said CEO Steve Nicol.

“Normally, a wireline intervention means making eight to 10 runs to shut down the well,” Mr Nicol said.

“Because the eRED tool requires only one run, that part of the process is significantly reduced, speeding up the entire operation, bringing cost savings to operators and reducing risk,” he said, noting a significant percentage of wireline runs are unsuccessful due to sticking or other complications.

The system achieves the same results as conventional plug and prong technology without requiring repeated intervention jobs to deploy or retrieve plugs when a barrier needs to be installed or removed. “This streamlined approach gets the well back online more quickly,” Mr Nicol said. In one subsea completion operation, eRED saved an operator close to $900,000 by reducing the slickline runs from eight to one, he noted.

The eRED device operates as a series of open-and-close actions triggered by specific well events or conditions. After responding to a trigger, the eRED detects another trigger and initiates the appropriate action for that, repeating the pattern. It can be opened and closed as many times as necessary without any intervention.

The eRED system has been used by 14 operators in 23 fields in the UK and Norway. The company is looking to expand its use for the more challenging deepwater arenas of Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico, including high-pressure, high-temperature wells. Mr Nicol acknowledges this move will require another “step-change” for the technology. Red Spider deployed the first installations of eRED in Australia in August.

The eRED portfolio now includes eRED-FB, a tubing-mounted version that eliminates slickline interventions from completion operations, and PowerBall, a reservoir isolation barrier for both cased and open-hole wells that can be remotely opened and then closed during lower completions. The system can be re-opened later for production.

A key aspect of subsea interventions goes beyond technology. Pre-planning, fully developed contingency plans and innovative ways of using conventional methods are critical in solving the complex challenges that today’s wells present.

“Well intervention operations are very costly, and anytime we can innovate with existing technology is a benefit,” said Bob Murphy, global business manager, Thru Tubing Business Unit-Packers for Weatherford International. “In particular, finding ways to convey the tools on wireline delivers a lower cost to the client and a reduced footprint.”

To that end, the company is developing systems such as the one-trip patch, or straddle, system for use in subsea monobore wells where some zones need to be shut off because they are producing water or gas due to leaks in tubular components. The system is retrievable, has a V-zero rating and can be deployed on wireline in lengths of up to 40 ft in one trip.

In the UK region of the North Sea, Weatherford combined two conventional tools to isolate a zone in a well where the lower formation was producing water. In this case, the operator needed to set a temporary plug to isolate the lower water-producing zone but also avoid an expensive trip back into the well to retrieve the plug. Using a monohull light well intervention vessel, a packer and an electronic shut-in device operating on battery timer were deployed on a wireline to set a bridge plug.

The plug was left in the closed position, with the timer set to open it a year later. This allowed the operator to complete the upper zones until the valve was opened so production could be re-established in the lower section of the formation. “By combining existing technologies in a novel way, we were able to avoid a second intervention, making what could have been a very expensive operation cost effective,” Mr Murphy said.

Conventional tools also were used successfully in a horizontal well in West Africa, where the operator needed to set a packer with a sand screen below after the original screen deployed in the gravel pack completion had failed. “Instead of bringing in a rig or using CT to do this remedial operation, we deployed the packer and sand screen with an electric line tractor on a wireline,” he explained.

In the Campos Basin offshore Brazil, an inflatable retrievable production packer was used successfully for a well abandonment operation that had complications. Pipeline pigs, which had been pumped to the production facility to flush the flow line, had become stuck, leaving production fluid in more than 4,500 ft of the line. Using a remote operating device with a high-pressure water jet, the packer was installed with a flexible deployment line mounted on a pipe-laying barge. After two failed attempts to get into the flow line, the packer assembly was inserted at the open end of the flow line that had been cut downstream of the pigs. With the set-up in place, water was then pumped, displacing 862 bbl of production fluid.

The first-of-its-kind undertaking was successful and has since been used for two similar operations. In all three cases, the flow lines and production risers were recovered and have been used on other wells.

“When we look at situations like this, especially as the industry moves into the deep and ultra-deep waters, we have to plan in advance, and we must have contingencies in place and tools available so if something happens, we can go right to the next step,” Mr Murphy said. “Having a decision tree in place with all the contingency plans covered, allows the process to run smoothly, with limited to no downtime between the phases of the operation.”

pls i need an informention about operating system of the hydralic valves