Industry eager for repeat of Brazil pre-salt boom offshore Angola

Continental drift theory supports hopes that this African nation also holds working petroleum system beneath the salt layer

By Tako Koning, Gaffney, Cline & Associates

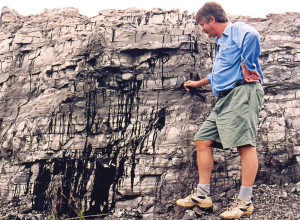

Angola’s very first oil event dates back to the late 1700s when the Portuguese colonialists discovered oil seeps and asphalt deposits at Libongos near Caxito, 50 km northeast of Angola’s capital city of Luanda. They shipped some of the asphalt to Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro to be used as caulking material to prevent leakage in the hulls of their ships.

Then, more than a century later, in 1915 the Portuguese oil company Companhia de Pesquisias Mineras de Angola (PEMA) carried out the first drilling in Angola in the Dande River valley near the village of Barra do Dande in the Bengo Province, some 40 km north of Luanda. The first well, Dande-1, was drilled to a depth of 602 m and was plugged and abandoned. PEMA drilled a total of seven wells in the Dande River area, all of which were abandoned. However, Dande-4, drilled in 1916 to a depth of 857 m, was tested and flowed at 6 bbl of oil per day (bopd), representing the first flow of oil in Angola. Sporadic exploration drilling over the next 40 years proved unsuccessful.

A key milestone occurred in 1955 when the onshore Benfica oilfield was discovered just south of Luanda. The discovery was drilled by the Belgium-based oil company Petrofina (Fina). Oil production began in 1956 from the Benfica field. Thus, 41 years had passed from the first drilling for oil in 1915 by PEMA and the commencement of oil production in Angola. The oil was pumped through a small-diameter pipeline to a refinery built and operated by Fina in Luanda.

In 1968, Cabinda Gulf Oil Co (CABGOC), a subsidiary of Pittsburgh, Pa.-based Gulf Oil, made Angola’s first offshore discovery: the Malongo field. This resulted in Angola’s first offshore production, commencing in 1969.

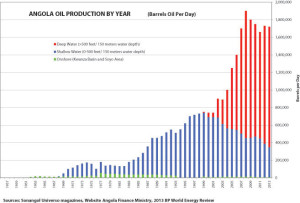

By 1996, Angola was producing approximately 700,000 bopd when a seminal event occurred: the discovery of the Girassol field in Block 17 by the French oil company Elf Petroleum in 1,300 m of water, 140 km off the coast of Angola.

The Girassol discovery stunned the industry because finding oil so far offshore – and in a new geological formation – was totally unexpected. Additional drilling by Elf proved Girassol to be a giant find, with the oil-bearing reservoir located in ancient river-deposited sandstones and conglomerates of Oligocene age, 25 million years ago.

This led to many more such discoveries in the Oligocene and Miocene sediments (the latter some 15 million years old) in the deep waters of Angola. These include discoveries by Chevron in Block 14, Esso in Block 15, Total in Blocks 17 & 32, BP in Blocks 18 & 31, the state oil company Sonangol in Block 4/05, ENI in Block 15/06 and Maersk Oil in Block 16.

The success of Girassol and the follow-up oil discoveries led to a burst in Angola’s oil production. By 2008, the country’s oil production had reached nearly 2 million bopd. Of Angola’s current estimated production of approximately 1.7 million bopd, around 75% is from the Oligocene and Miocene-age reservoirs.

The pre-salt of Brazil – implications for Angola

In 2006, another milestone event happened across the Atlantic Ocean in Brazil that holds great potential for Angola: the discovery of the Lula oilfield in the offshore Santos Basin. This field was originally called Tupi but was renamed Lula after Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

Why would a discovery in faraway Brazil have significance for Angola? The explanation is disarmingly simple. In 1915, the German geologist Dr Alfred Wegener first proposed the theory of continental drift, by which parts of the Earth’s crust slide slowly over its hot liquid core. Dr Wegener hypothesized that 200 million years ago, there was a gigantic supercontinent, which he named Pangea, meaning “all Earth.”

We now know, on the basis of extensive paleontological research, outcrop and seismic information, that in Early Cretaceous time (135 million years ago), Angola and Brazil were part of Pangea – literally “joined at the hip.” Therefore, the geology of both is identical.

However, about 130 million years ago, South America began to draw away from Africa. As the continents separated, an extensive rift valley was formed, containing large lakes full of plant and animal material that had washed off the adjacent highlands. These rift valleys are similar to the present-day East Africa rift system. The two continents continued to move apart, and the sea transgressed into the rift system. Since the area invaded by the sea was still long and narrow, from time to time the sea was cut off by adjacent land masses and the water evaporated, leaving behind ever deepening deposits of salt. Further continental separation resulted in the laying down of more thick deposits of marine sediments.

Fast-forward 130 million years, and Brazil is now 7,000 km west of Angola. The discovery of the Lula oilfield in Brazil was truly a milestone event for Angola – by the implication that the Santos Basin deposits could be duplicated in the Kwanza and Namibe Basins, to which they were once joined.

The well that found the Lula field was Tupi-1. It was drilled by Petrobras in the deepwater part of the Santos Basin – in water depths of 2,100 m, with the well drilled a further 5,200 m below the sea floor. The Lula field is in a high-pressure, high-temperature environment beneath a massive, 2-km-thick salt sheet. The cost of Tupi-1 was a staggering $240 million, but the reward was finding a mega-giant oilfield and the opening up of the pre-salt oil play in Brazil.

Accordingly, Lula was the first of the now-famous pre-salt oilfields in Brazil, proving that a working petroleum system exists beneath the salt layer of the Santos Basin. The oil source rocks are the organically rich lake shales, the reservoirs are porous limestones and dolomites known as microbalites, and the seal above the reservoirs (which keeps the oil trapped) is the thick, impervious salt layer.

According to Petrobras, the field has recoverable reserves of 5.3 billion bbl of oil and 6.9 trillion cu ft of gas. Petrobras (65% working interest) operates the field on behalf of partners BG Group (25%) and Galp Energia (10%). Two floating production storage & offloading units (FPSOs), Lula Pilot and Lula NE, are currently producing the Lula field. The wells in Lula are averaging 25,000 bopd of production per well.

An oilfield even larger than Lula was discovered in the Santos Basin in 2010. Petrobras, on behalf of the Brazilian regulator Agencia Nacional do Petroleo (ANP), discovered Libra in 2,000 m of water. The discovery well intersected a continuous oil column of 325 m in carbonate rocks below the salt. Test results indicated good-quality light oil with 27° API.

In October 2013, a consortium of Petrobras (40%), Shell (20%), Total (20%), CNPC (10%) and CNOOC (10%) was awarded a 35-year production-sharing contract to develop Libra. The consortium agreed to pay Brazil’s government a signature bonus of $6.7 billion for the field rights. Shell has described the field as one of the largest deepwater oil accumulations in the world. According to ANP, Libra has the potential of 8 billion to 12 billion bbl of recoverable oil resources. Libra’s total gross peak oil production could reach 1.4 million bopd, according to ANP.

Since the discovery of Lula, many more pre-salt oil and gas fields, including Libra, have been found in the Santos Basin, as well as in the more northern Campos Basin. Oil industry analysts, such as Wood Mackenzie and IHS Energy, have estimated that Brazil’s pre-salt reserves could amount to some 20 billion to 30 billion bbl of recoverable oil, while ANP has stated that the reserves could be as much as 50 billion bbl.

The impact of the pre-salt discoveries on Brazil has been dramatic: Brazil’s oil production is now at 2.1 million bopd, of which 545,000 bopd is from the pre-salt fields already. About 300,000 bopd is from the Santos Basin, and 245,000 bopd is from the Campos Basin. Petrobras believes that output from these reserves will grow and bring Brazil’s output to at least 4 million bopd – nearly double the country’s current production.

When the conjugate margins of Angola and Brazil are juxtaposed back into pre-continental drift time, this clearly shows that the Santos and Campos Basins were located directly adjacent to Angola’s Namibe, Benguela and Kwanza Basins.

Angola’s recent pre-salt successes

For petroleum explorers, the deepwater Kwanza Basin has become one of the most exciting basins in the world. A historic event occurred in 2011 with the awarding of 11 pre-salt blocks by Sonangol to BP, Cobalt International, ENI, Total, Repsol, ConocoPhillips, and Statoil.

In 2011, the Danish oil company Maersk Oil had already embarked on drilling in deepwater Kwanza Basin Block 23. In early 2012, it announced the results of its first well, Azul-1, drilled specifically to evaluate a pre-salt prospect. The well was drilled in a water depth of 902 m to a depth of 5,330 m. Azul-1 flowed 3,000 bopd. In the history of Angola’s oil industry, this well is historic since it was the first deepwater well drilled in the Kwanza Basin that flowed oil from the pre-salt.

The announcement of the Azul-1 oil discovery was shortly followed up by the announcement by Houston-based Cobalt International of the success of its first well drilled in Block 21 in the Kwanza Basin, which tested high-quality oil from the pre-salt. This well, Cameia-1, was drilled in a water depth of 1,680 m. An extended drill stem test was performed on Cameia-1, which flowed at a sustained rate of 5,010 bopd of 44° API oil and 14.3 million cu ft of associated gas per day – thus, approximately a total of 7,400 bbl of oil equivalent per day. Cobalt reported that the well confirmed the presence of 360 m of gross continuous oil column with over 75% net-to-gross. No gas-oil nor oil-water was evident on the wireline logs. Cobalt stated that it believed that the well has the potential to produce in excess of 20,000 bopd.

Approximately one year later, Cobalt announced another important pre-salt discovery – the Lontra-1 well drilled in Block 20. This well was drilled to a total depth of 4,195 m and penetrated 75 m of high-quality reservoir section. The well produced at a stabilized flow rate of 2,500 bbl per day of condensate and 39.0 million cu ft of gas per day. According to Cobalt, the flow rates were significantly restricted by the surface test facilities on the drilling rig.

An additional encouraging well was drilled by Cobalt in the first half of 2014. The Orca-1 well was drilled in Block 20 to a depth of 3,872 m and intersected 76 m of pay in a section that Cobalt described as having excellent reservoir quality. Orca-1 flowed at a facility-constrained rate of 3,700 bopd and 16.3 million cu ft of gas per day, with minimal drawdown. Cobalt has a 40% working interest in Block 20 and is partnered by Sonangol and BP, each with 30% working interests.

The pre-salt beyond Angola

The discovery of the Tupi oilfield in Brazil’s Santos Basin also led the international oil explorers to look along the entire West Africa margin.

Exploration wells focused on extending the pre-salt oil play southwards from Angola have been drilled offshore Namibia but without success. These wells were drilled in the last two years by BP, Petrobras, Repsol and the Brazilian company HRT Oil & Gas. Oil industry analysts have reported that no salt has been encountered in any wells drilled offshore Namibia and it’s likely that pre-salt oil-generating source rocks are not present in Namibia.

However, exploration in the pre-salt northwards of Angola exploration has met with encouragement beginning in Gabon. In 2012, Total announced that the Diaman-1B well, the first well to explore in the pre-salt of deepwater Gabon, encountered up to 55 m of gas and condensate pay in pre-salt sandstones, thus confirming the existence of a working petroleum system in the pre-salt in deepwater Gabon. The water depth of Diaman-1 was 1,730 m and the drill depth was 5,585 m. Partners in the well included Cobalt and Marathon Oil.

In 2012, in Congo-Brazzaville ENI encountered success in the Nene Marine-1 pre-salt oil discovery. The well was drilled in the shallow waters 17 km off the Congo-Brazzaville coastline in a water depth of 24 m. The reservoir is not pre-salt microbalite carbonates similar to the pre-salt oil discoveries of Brazil and Angola but rather is pre-salt sandstones. The discovery was tested at 5,000 bopd of 36° API oil. A third well, Nene Marine-3, was drilled 2 km westwards from the discovery well. It confirmed the hydrocarbons and reservoir continuity. ENI estimates the in-place resources at 1.2 billion bbl of oil and about 1.0 trillion cu ft of gas.

In February 2014, ENI’s upstream Chief Operating Officer, Claudio Descalzi, told analysts that the Nene Marine discovery had “cracked the pre-salt code in Congo-Brazzaville” and that further potential will be sought by ENI in a dedicated 2014 exploration program.

The most recent news concerning successful pre-salt exploration outside of Angola was ENI’s announcement on 31 July 2014 about drilling a significant new pre-salt gas and condensate discovery in the shallow waters of Gabon. ENI revealed that the Nyonie Deep-1 well was located in 28 m of water about 13 km off the coast of Gabon and was drilled to a depth of 4,314 m. The well intersected a 320-m-thick hydrocarbon-bearing section in a pre-salt clastic sequence of Aptian age (110 million years old). According to ENI, the initial potential in-place resources are 500 million bbl of oil equivalent.

The recent pre-salt discoveries in Gabon and Congo (Brazzaville) are encouraging. However, the reservoirs are sandstones, so these discoveries are not fully geologically equivalent to the microbalite carbonate reservoirs that are so prolific in Brazil and that are being discovered in Angola.

The future

As the oil industry keenly watches the success or failure of more drilling in West Africa and especially in Angola targeting the pre-salt, everyone is questioning if the success of Brazil’s pre-salt oil play will truly be duplicated in Angola and if Angola can, like Brazil, eventually double its oil production. The answer lies in the geology. Petroleum geology is not a precise science since geologists search for oil and gas in ancient strata lying at great depths some 5 to 7 km beneath the sea floor. The drilling targets are defined by seismic waves, which must penetrate through the thick salt layer and then be reflected back to the surface to be recorded as seismic lines. Accordingly, as with all oil and gas exploration in minimally explored sedimentary basins, a great deal of risk is involved.

These are exciting times in Angola’s oil industry. At present in Angola, deepwater Kwanza Basin wells are being drilled by Statoil, ConocoPhillips, Repsol, BP, Cobalt and very soon by Total. The outcome of these wells is of great interest to oil industry observers and analysts.

Angola and Brazil have a common cultural heritage as both countries were colonized by Portugal. Portuguese is the national language of both countries. Will the cultural commonality also extend to a commonality in the pre-salt oil and gas reservoirs? Geologists will emphasize that you can speculate forever on such issues, but there is the often-used expression that “you just don’t know what you have until you drill.” In the case of Angola, by early to mid-2015, the answers to these questions will be much clearer.

Tako Koning is a Canadian senior petroleum geologist living and working as a consultant for Gaffney, Cline & Associates in Luanda, Angola.