Automation, software, mobility lead advances in drilling packages

Manufacturers trend toward ‘smart iron’ that helps rig crews do their jobs

By Bruce Nichols, Contributing Editor

The drilling industry is on the cusp of big changes, with improved automation packages and new equipment designs emerging from manufacturers faster than they can be put in place by contractors and operators. But adoption of new ways of doing things likely will accelerate because oil companies have seen costs rise and oil prices level off. They need more efficiency. At the same time, Macondo has boosted regulator pressure on safety, and there’s a need to speed up training of new employees as older workers retire.

Changes offshore are particularly striking, as automation advances with the launch of every new rig. National Oilwell Varco (NOV), for example, highlights software improvements to smooth the operation of individual rig systems and to manage several systems at once, safely and efficiently. The company’s Smart Machine Integrator (SMI) suite includes software for Pipe Interlock Management (PIM) to ensure safe pipe handling and Multi-Machine Control (MMC) to make it easier for drillers to oversee the whole drilling process.

SMI also has anti-collision system software to keep machines from stepping on each other’s toes and a machine control diagnostic tool to catch glitches in software and mechanics before they become big problems.

Karl Appleton, NOV’s VP of Marketing & Planning, describes PIM this way: “As you are handling pipe on a rig, there are a lot of handovers from one machine to the next as you are going from finger boards to pipe handlers to top drives and roughnecks and slips. Handover points are notoriously the point where one thing happens and the other doesn’t. So we came up with Pipe Interlock Management, which looks after the people, equipment and process interactions as pipe is moved around.”

PIM allows the next step to start after confirming the previous one is finished.

The MMC part of the SMI suite oversees the processes that put pipe to work after it has been retrieved from the pipe deck and delivered to the drill floor – attaching it to the rest of the drilling equipment and starting it running downhole.

Shawn Firenza, NOV Senior Director of Product Technical Support, said increasing mechanization has made it possible to sequence complex tasks. “There are rig designs out there that, in the processing of tripping in a stand of pipe, you would need one person to control seven machines,” Mr Firenza said. MMC enables the driller to concentrate on the overall task rather than having to monitor and control each machine, he said, adding that NOV is expanding MMC to riser-handling systems and horizontal pipe-handling systems.

“Increasing safety is a big piece of it,” Mr Firenza said, “and it reduces operator fatigue and ensures consistent operations.”

At different points during a 12-hour shift, the same crew is likely to do the repetitive tasks involved in tripping in and out of the hole at varying rates. Weariness can set in, and boredom may take its toll. “Especially in a long tripping scenario, you’ll see the change in their tripping speed,” Mr Firenza said. MMC can allow for much more consistent operations.

The SMI suite’s anti-collision system uses position sensors to prevent collisions between pieces of equipment operating on the same drill floor, and the machine control diagnostics tool monitors machine performance to do proactive maintenance and reduce downtime.

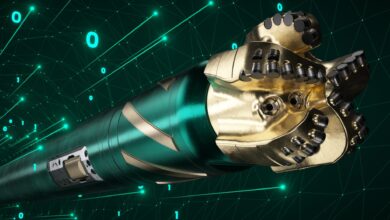

With mechanical and digital improvements downhole, NOV is working on the Bottom Hole Assembly Tool. It makes it safer and easier for crews to assemble the drill bit and the specialized tools, many of them electronic, that follow the bit into the hole.

“We looked at creating something where we could handle a BHA at the drill floor, something that was less cumbersome than having to change constantly from one slip size to the next slip size, that got people out of standing directly in the red zone when a BHA is being screwed together,” Mr Appleton said.

“It’s got a range of sizes so you don’t have to change slips often, and it can be worked remotely so you don’t have people in the danger zone. It allows you to make up complex BHAs quicker and safer than if you were just doing it manually,” he continued.

“With these tools, we are not yet fully automating but mechanizing at a much higher level to avoid people having to touch pipe and equipment as much,” said Svein Ove Aanesland, NOV Director of Strategic Rig Packages.

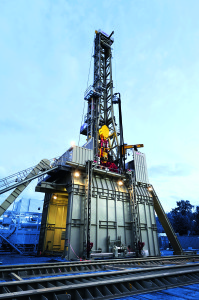

Another example of innovation in drill packages is Huisman’s Dual Multi-Purpose Tower (DMPT), which is changing the traditional appearance of a drillship, said Ed Adams, Senior Business Development Manager for Huisman in Houston.

The DMPT features a welded box girder-type load-bearing structure with two centers of activity: a drilling activity center on one side and a construction activity center on the other side. It looks more like a silo or a petrochemical cracking tower than a traditional latticework derrick.

With the traditional derrick, the hoist is typically inside the latticework but exposed to the weather. With the DMPT, there are two hoists on the drilling side and one or two hoists on the construction side, all of which are inside the vertical box structure – out of the weather and protected for maintenance purposes. In addition to adding redundancy, the dual drawworks arrangement eliminates the conventional dead-line anchor and the need for a cut-and-slip procedure for the drill line.

Because there is no latticework derrick around the activity centers, there is no V-door limitation on pipe stand lengths or equipment heights. A hoistable floor on the construction side of the tower can be raised to allow BOPs and trees to be skidded or hoisted in directly to the well center or the moonpool area.

Huisman also touts a splittable block, which can change reeving from 16 to four cable strands with the push of a button. The advantage is the block combines the strength to lift heavy items slowly with the speed to lift lighter items rapidly; the four-strand setup operates faster than the 16-strand mode.

With no V-door limitation on length of pipe stands and the ability to split the block, tripping in and out of the hole can be accomplished much more rapidly than can be done aboard traditional rigs. Current systems can handle 135-ft drill pipe or casing stands. Huisman’s latest DMPT can handle 180-ft stands. Further, on the construction side of the tower, the subsea BOP and risers are run to the mudline and then transferred to the drilling firing line by way of a transport cart in the moonpool. Without the V-door limitation, new versions of the DMPT are set to run up to 150-ft riser sections, improving the speed of riser-running operations that utilize 75-ft or 90-ft risers typical on standard dual-derrick rigs.

In addition to the hoists, all other key drill tower equipment, such as passive heave compensation cylinders, are inside the vertical box structure. Located out of the weather means less maintenance, and the top of the tower can be removed to shorten the height of the vessel, allowing passage under bridges across the Suez and Panama Canals and the Bosphorus.

Integrating the whole system into the design of the drillship has resulted in smaller, more compact vessels with more on-deck storage capacity, Mr Adams said.

NOV and Huisman both say automation could result in fewer personnel needed to do the work – but that is not the main goal. “Although a case can be made for reduction of manpower due to automation, the main benefits aim at consistent operations, which means overall speed increases through efficiencies and much safer operations,” Mr Adams said.

Onshore advances

Innovation in drilling packages is also occurring onshore. Although lower-cost, smaller-scale operations demand less automation than offshore, shale plays are driving considerable innovation.

Schramm touts its T500XD Telemast drill rig, which can be delivered to a site in 10 truckloads, has a 500,000-lb hookload capacity and can drill to 15,000 ft. It also offers 360° walkability for the pad drilling applications that have become common in shale plays.

The rig has a control cabin with joystick controllers for drilling, and it has automated, hands-free pipe handling. It is self-erecting in less than a day without requiring a crane, and it can run with a crew of three.

“It has a much smaller footprint and is quicker to mobilize and demobilize. It’s semi-automated so that you are getting folks out of harm’s way,” said Ed Breiner, Schramm CEO.

Mr Breiner said his company is focusing on ergonomics to reduce driller fatigue, including communications connectivity to operators and other third parties so they can monitor the operation via the Internet or satellite links.

He also speaks in terms of “smart iron,” equipment that helps people do their jobs. One example is the design of pipe handlers with automated stops, so the machine returns to the exact same position every time. The manual approach can put a worker in harm’s way and demands much more precision and consistency. Controls are also becoming more intuitive, especially for younger workers.

“There are touchscreens and two joysticks as opposed to 19 valve handles on a mechanical, older-style hydraulic rig. Algorithms help calculate the penetration, weight on bit, etc, so you know more and you have systems feedback that automatically interprets the feed rate and penetration,” Mr Breiner said. “Things that historically have been done by feel now are done with information technology.”

Further work is being done to allow automatic electronic access to sensitive parts of the machines to monitor their condition and facilitate timely maintenance.

At the 2014 Offshore Technology Conference, Schramm introduced the T250XD, which uses the same operating system as the 500 but has only a 250,000-lb hookload.

At Bentec, one new innovation is its soft torque rotary system, a software solution to avoid stick-slip problems and to increase the rate of penetration for more drilling efficiency. The company is also planning to launch a 750-ton top drive and an upgraded version of its 500-ton top drive, the TD-500-XT, at the end of the year, said Andreas Rentzsch, Vice President of Sales.

The German-based company is working on systems that combine information at the surface with information downhole to guide drilling in a push toward total automation of the process based on real-time downhole conditions.

On the company’s 480-ton Euromatic rig, one key feature is the technology and software that controls various systems, Mr Rentzsch said. “Our Euromatic rig has a fully automated pipe-handling system to significantly improve safety and reduce the risks associated with manual pipe handling. These new pipe-handling techniques remove the need for personnel on the drill floor and maximize drilling efficiency.”

One advantage is the tripping speed. Most automated rigs can reach an average tripping speed of 200 m to 300 m an hour, running pipe in the hole or pulling it out as part of drilling operations. The Euromatic rig can reach 660 m/hr without manual assistance, he said.

In another company’s bid to advance drilling packages, Integrated Drive Systems, or IDS, introduced its intelligent drawworks last spring.

“It’s a drawworks that has a lot more sensors and communications back to the main PLC (programmable logic controller) system,” said Norman Myers, Co-founder and Managing Director, referring to the system’s main computer. “It allows the system to do predictive maintenance to prevent unexpected failures by trending the condition of the mechanical equipment.”

The system measures things like bearing temperatures, lubrication life and other signs of wear and tear that necessitate maintenance.

The new machine also is lighter and smaller so it can be transported into areas of new activity, such as Pennsylvania, where roads are more load-limited and narrower than, say, in West Texas, southeastern New Mexico or Oklahoma.

IDS, which also specializes in electrical systems for drilling rigs, is working on a 4,160-volt system for land rigs to simplify the traditional 600-volt system. Drilling in shale plays requires rigs to do a lot more moving around, and the 600-volt system has more cables to handle, Mr Myers said.

“It’s not unusual to have 20 or more 600-volt power cables that go between the drilling rig and the main power house,” he continued. “They have to be connected and disconnected, and every time you do that, it introduces another potential failure point. Basically we have created a power system that reduces our power cable down to one cable because we are operating at a higher voltage.

“It actually runs on a reel, so we connect it once, and then we don’t disconnect it when we are walking the rig from one well to another. We may eliminate more than 20 of the 600-volt cables and cable connectors and replace that with one connector, one cable.”

Business model

Perhaps the biggest change that the industry needs, Huisman’s Mr Adams said, is not new software or improved machines, but a new business model that better harmonizes the interests of oil companies, drilling contractors and equipment manufacturers around innovation.

“It takes three to tango,” Mr Adams said, quoting Huisman owner Joop Roodenburg, meaning all parts of the business chain need to work together better to improve efficiency and lower well costs.

The traditional dayrate drilling contract model helped build the industry by guaranteeing capital investment in rigs. Oil companies were willing to operate on a dayrate basis as long as well costs were low and their profits rose with oil prices.

But the situation is different now, Mr Adams said. Macondo has raised costs related to regulatory compliance. The move into deeper waters and more challenging geological and climatic environments is also raising operating costs. And oil company return on capital employed has dropped as oil prices have flattened around $100/bbl.

Oil companies are now looking for lower well costs, while drilling contractors are still driven by dayrate revenues. “You have a misalignment here,” Mr Adams said.

It’s evident that manufacturers continue to be interested in innovating, and when oil companies and drilling contractors find better alignment of objectives – maybe with more incentives or penalties built into dayrate contracts – then innovation will speed up, Mr Adams said.

Jesse Maldonado contributed to this report.