NOCs from Africa, South America seek to boost competitiveness by investing in gas, renewables

Ecopetrol, Sonangol and NNPC moving to embrace lower-carbon projects in bid to attract external funding, develop long-term path forward

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

Amid the decarbonization of the global economy, international oil companies (IOCs) aren’t the only ones facing rising ESG pressures. National oil companies (NOCs) from Africa to South America are also contending with calls – from both their citizens and investors – to adopt stronger protocols for reducing carbon emissions and to take a stronger stance on climate change. Some have also been urged to diversify into renewables; realigning portfolios to a low-carbon future is now seen as a key step to attracting external investments.

“Peak oil is around the corner, and NOCs must try to rapidly modernize as much as possible in order to provide the needed liquidity to support other sectors of the business and provide the infrastructure for our national economy,” said Umar Ajiya, CFO of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corp (NNPC). Speaking on a panel during CERAWeek by IHS Markit on 2 March, Mr Ajiya was joined by representatives from Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Angola’s Sonangol to discuss NOC strategies for the near- and long-term future.

ESG has been on Ecopetrol’s agenda for years. Since 2011, it has been included on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, a global benchmark for the sustainability performance of publicly traded companies. Still, it has continued to see an increasing emphasis on ESG from both investors and potential investors.

Ecopetrol has adopted the view that the energy transition is not a threat to its business but an opportunity for growth, CFO Jaime Caballero said. This means ESG concerns have become “a core and central part” of the company’s agenda, he said.

“When we look at the degree to which we are addressing decarbonization and the degree to which we’re addressing the broader ESG matters in a corporate role, we’ve decided that we need to go from having a reactive stance to having a very proactive stance,” Mr Caballero said.

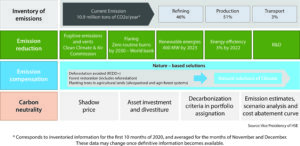

On 25 March, Ecopetrol announced its plan to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 for scopes 1 and 2. The plan calls for a 25% reduction of its direct and indirect CO2e (CO2 equivalent) emissions (scopes 1 and 2), compared with 2019 baseline levels. It also seeks to reduce 50% of total emissions associated with the company’s value chain by 2050 (scopes 1, 2 and 3). This makes Ecopetrol the first oil and gas company in Latin America to establish this type of ambition.

Its decarbonization roadmap calls for implementing additional technological options to reduce fugitive emissions and venting from routine gas flaring, as well as energy efficiency in operations. Ecopetrol also referenced the potential related to energy storage through batteries, “once the competitiveness and effectiveness of these alternatives is achieved,” the company said in its March announcement.

Emissions management throughout the supply chain will also be a key focus. Further, the company plans to develop initiatives related to hydrogen and carbon capture, use and sequestration.

This strategy does not indicate a shift away from oil and gas for Ecopetrol, however. At CERAWeek, Mr Caballero indicated that oil and gas production would remain at the core of the company’s business. Approximately 77% of Ecopetrol’s 2021 CAPEX is allocated to upstream oil and gas development, with the company expecting to produce approximately 700,000 BOED this year.

What the net-zero roadmap does mean is the company has to provide a “more balanced value proposition” for its shareholders, he explained. Diversification into renewables, for example, can help the company to build stronger resilience to oil price variability and create additional value.

“We’re seeing a market that’s increasingly interested and actually vested in the energy transition,” Mr Caballero said. “We see a market that’s very interested in having visibility around the longevity of the oil and gas business, how we will compete over the 5- to 10-year time frame, into 2030. Our ability to compete for capital and funding in competitive terms is going to be directly related to that context.”

As part of a larger focus on transparency and accountability in ESG – something that Ecopetrol launched in the past year – the company said it will start reporting on its progress toward stated sustainability goals as part of its earnings reports. In January, Ecopetrol was also among 60 other companies that agreed to adhere to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics. The metrics offer a core set of 21 disclosures focused on environmental progress. They include disclosures on greenhouse gas emissions, land use and ecological sensitivity, water consumption and withdrawal in water-stressed areas, and the implementation of recommendations from the WEF’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

Mr Caballero said that prioritizing openness has proven positive for Ecopetrol over the past year. “It means a level of visibility and a level of transparency around these non-operating metrics that we didn’t have before,” he explained. “We see tremendous value in doing that because it facilitates the conversation with the markets and even enables access to capital. Last year, in the midst of COVID, we actually went out into the capital markets and got $2 billion in funding. We found this sort of conversation was very well received by the market.”

Sonangol, Angola’s state-owned oil producer, is looking at similar steps to diversify its portfolio, said Sebastião Gaspar Martins, Chairman of the Board. He referenced the work that Equinor has undertaken to transition from an oil and gas company to an overall energy company, saying that Sonangol will also ultimately make that transition.

By 2022, the company expects to have production of renewable energy. It is working with Eni on a 50-MW solar plant in the southwestern province of Namibe, part of a joint venture the two companies launched in 2019 to explore renewable development. A research center in the Kwanza Sul province, just south of Angola’s capital city of Luanda, is also being planned to aid in the development of hydrogen production projects.

“We are aware of the reduction in investment for projects with high carbon emissions, like with oil platforms,” Mr Martins said. “We need to show an approach to our partners and investors that we are a responsible company. We have several examples already established in our company. We are still taking our oil and gas business seriously, but we are also moving to the renewable sector.”

NNPC has focused building its natural gas business as part of its ESG initiatives. The 381.5-mile AKK (Ajaokuta-Kaduna-Kano) natural gas pipeline aims to create a gas supply network between the northern and southern parts of Angola and is estimated to have upwards of $5 billion in investment. Besides encouraging the use of domestic gas, the pipeline can also help to reduce gas flaring in the Niger Delta, according to Sonangol. The AKK comprises the first phase of the 800-mile Trans-Nigeria Gas Pipeline connecting Nigeria and Algeria, which is expected to transport between 11 million and 24 million cu m/day of natural gas.

NNPC also secured $3 billion in financing last year for NLNG Train 7, a joint effort among NNPC, Eni, Total and Shell. The project is a major part of the country’s gas expansion plan and is expected to boost Nigeria’s LNG output by more than 30%.

Despite the hefty price tags that come with these pipeline and LNG projects, NNPC believes they offer the best route for Nigeria to boost investment into its oil and gas sector, Mr Ajiya said. The country holds the largest natural gas reserves on the African continent and aims to be a major exporter of LNG, he said. Further, these types of projects align well with the sustainability goals being adopted by IOCs, on which NNPC and other NOCs rely heavily for project funding.

At the same time, however, Mr Ajiya said economic realities must be acknowledged. As Nigeria struggles with high inflation, low per-capita income and lagging GDP growth, the country has to focus on profitability. “What we have done strategically is try to focus more on gas utilization, gas power and gas-based industries,” he said. “We have ample gas resources that can add value. We are also addressing the challenge before us by optimizing costs. We need to select projects purely on the basis of viability and bankability.”

Government support will have to be another key part of NNPC’s future path, he continued. Nigeria is still trying to pass the Petroleum Industry Bill, an ambitious plan to overhaul the country’s oil and gas sector that has been stalled for more than a decade.

The bill aims to streamline Nigeria’s complex petroleum regulations by repealing several statutes and simplifying its tax and fiscal regime. This includes replacing the country’s petroleum profit tax with a new hydrocarbon tax that covers condensates and natural gas liquids, in addition to crude oil. Investment tax credits and allowances would be replaced by a general production allowance that will reduce taxable profits.

Further, government funding for NNPC would be eliminated – the company would remain government-owned but would operate on a commercial basis.

With the bill sitting in limbo, Mr Ajiya said, investors have been hesitant to put money into Nigerian projects. The changes to the tax and royalty structure proposed in the bill, as well as the restructuring of NNPC and the lack of a provision that explicitly preserves the terms of existing oil investments, could have a significant financial impact on IOCs working in Nigeria.

In January, Total spoke on behalf of the Oil Producers Trade Section (OPTS) at a government hearing on the bill. The OPTS encompasses 30 operators including Total, Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Eni. In his statement, Mike Sangster, Total Nigeria Managing Director at the time, said the OPTS doesn’t believe the bill would provide a favorable environment for future investments in the country. For example, the bill should not include a hydrocarbon tax, as operators are already subject to income tax, Mr Sangster argued. Operators are also concerned that the bill does not explicitly protect existing contracts.

As of April, the bill was still moving through the country’s National Assembly, but Mr Ajiya said he believes it will pass by mid-2021. Despite OPTS objections, he believes the bill’s passage would help Nigeria to better compete for investments within the African subcontinent. Between 2015 and 2019, Nigeria was only able to attract approximately 4% of the $70 billion committed to new projects in Africa, according to OPTS.

“The choice between the big E&P companies is competitiveness, the fiscal regimes in the relevant jurisdictions in which they choose to operate,” Mr Ajiya said. “We have seen that, of the preponderance of investment coming into Africa, only a little portion of that has ended up in Nigeria simply because our fiscals have not been streamlined.” DC