Safety-critical task analysis is not a silver bullet, but it can help improve procedural integrity

Undertaking systematic process to identify human factors issues can lead organizations to focus on major accident hazards

By Varun Sarpangal, Marex

The term “human factors” has been in use for over four decades in the drilling industry. However, even today, there can be limited understanding in the field about what the term actually covers. Often, there is a misconception that it is just about human behavior.

While that is certainly part of the remit, human factors is mainly about engineering (or re-engineering) the tasks, work equipment and work environment in order to get the best out of the people who are carrying out the tasks.

The overall aim is to minimize the likelihood of accidents and improve safety in the workplace.

The drilling industry has seen some turbulent times of late. While companies continue to look to optimize their operational costs, the costs associated with human factors integration might appear to be a deterrent for companies. While it can be difficult to quantify the long-term financial benefits of human factors integration, the true benefit lies in what it can offer in terms of major accident prevention.

It is arguable that with all the cost-cutting measures the industry has seen over the past few years, the risk of human failure causing major accidents is now considerably higher. Organizations should remind themselves that the cost of carrying out these assessments and implementing improvement measures would be substantially lower than the cost of major accidents.

When “human factors” is used in the context of major accident hazards, it concerns the severe consequences that human failures can bring about in safety-critical industries, such as drilling. It is a statistically validated fact that a vast majority of major accidents have some level of “human error” as part of their root cause.

“Lack of situational awareness” is one example of human failure that appears in incident investigation reports. For instance, the driller not gleaning crucial information about certain changes in the well at the right time could result in a blowout that has catastrophic outcomes.

However, digging a bit deeper, it can be seen that there are underlying human performance influencing factors (PIFs) that lead to such human failures.

Examples of PIFs that might affect the driller’s situational awareness are fatigue, distractions or a high cognitive workload due to a poorly designed human-machine interface.

The best way to prevent human factors issues from leading to costly accidents is to proactively and pre-emptively carry out a systematic study to identify and understand the PIFs, and make sure they are brought to their optimal states and maintained during ongoing operations.

Safety-critical task analysis

Safety-critical task analysis (SCTA), a process that encompasses human reliability analysis (HRA), can help achieve this objective. The process consists of four key steps:

1. Identification of safety-critical tasks

Safety-critical tasks are defined as those tasks where human factors could cause, contribute to, or fail to reduce the effect of a major accident.

The first step of an SCTA involves identifying all safety-critical tasks. One of the primary sources of data that could be used for this step is the bowtie major hazard analyses for the drilling installation. Its output can be qualitatively analyzed to identify all the associated tasks that are required to make sure major accident hazard control and mitigation barriers remain in place and are effective. The resulting information will be a list of safety-critical tasks for further assessment and screening.

2. Prioritization ranking of safety-critical tasks

As task characteristics and the severity of consequence of human failure in carrying out the task correctly vary, some safety-critical tasks can be more critical than others. These need a more in-depth assessment. A process for allocating a priority ranking to each task has to be established.

There is guidance from the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) on assessment of safety-critical tasks and the Energy Institute’s guidance on SCTA, which could be used for the prioritization exercise. This guidance would have to be appropriately modified and tailored to suit the operations of the drilling installation.

Providing scores for the two aspects of task characteristics and the severity of consequence for each safety-critical tasks allows the tasks to be ordered by overall priority score. This can then be used to group the tasks into high, medium and low.

The organization can then start by analyzing the high criticality tasks, before moving on to the lower priority ones. The scoring and prioritization of safety-critical tasks should ideally be completed in a workshop setting with members of the workforce who have a detailed operational understanding of the tasks.

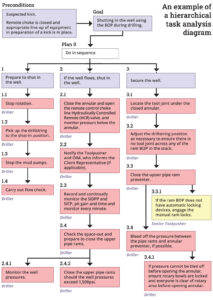

3. Development of hierarchical task analysis diagrams

In order to assess the levels of human interaction with systems and equipment, a suitable assessment tool that uses a systematic approach is needed to identify potential for human failures within tasks.

Task analysis methods are used to understand what is being carried out, where hazards may be present and where errors may occur.

Hierarchical task analysis (HTA), as the name suggests, places a hierarchy on the order of the tasks to be analyzed. It breaks down a given human-performed activity into goals, tasks and task steps.

The goal (the main task) is represented at the top level, and the sub goals (task steps) are represented at the next subordinate level. The task steps, in turn, may be broken into more detailed actions that personnel could take (sub-steps) represented as nested boxes below each task step.

The method produces a tree structure, along with an additional output being a list of tasks outlining their sequencing in order to meet the overall task goal. This allows work procedures to be analyzed, and various human errors and their subsequent consequences can be identified.

Alongside the official company procedures and work instructions for the safety-critical tasks, other information gathered from the worksite by the crew, such as completed walk-through talk-through (WTTT) templates, can be used as sources of input toward building the task steps.

The WTTT process consists of an experienced person demonstrating how the task is carried out onsite. It helps to understand task steps, identify likely error traps and aids discussion of how the operator might typically deal with them. It also helps in capturing and recording any deviations from or gaps between how the official procedures have been written (work as imagined) and how work is actually done on the ground (work as done).

4. Human reliability analysis

HRA is a process that uses a set of “guide words” similar to those used in a hardware HAZOP. The review team (similar to the one formed for the safety-critical task prioritization exercise) applies the guide words to the lowest level of the developed hierarchical task analysis in order to identify the possible errors that could arise.

The guide words and questions should be developed in line with established methods, such as predictive human error analysis and the systematic human error reduction and prediction approach.

This exercise ensures that any deviations or suggested improvements in the task design are identified and either corrected or incorporated.

When potential human errors are highlighted using the guide words, the team needs to identify the underlying PIFs, the likely consequences and the possibilities for recovery. The consequences of these human failures are then explored, along with existing prevention or mitigation measures in place.

If the resulting residual risk is still considered to be high, that is where the existing safeguards or recovery measures identified are deemed as inadequate. If none are identified, appropriate error prevention strategies are developed.

So, is SCTA a magic bullet that can prevent all human failures on drilling installations? Can human reliability on drilling installations be guaranteed by carrying out a desktop analysis such as the SCTA? The answer is definitely no. Human reliability on an installation can only be optimized by implementing a complete human factors integration program.

Going through the SCTA process will naturally help in achieving improved procedural integrity, which plays a key role in optimizing the task design. Beyond that, however, the process may not provide solutions to human factors issues.

What it will do, though, is highlight the various existing human factors problems in the workplace, including those at the organizational and management levels.

For any organization in the drilling industry looking to make a start with human factors, the SCTA exercise is an ideal stepping stone toward full human factors integration because:

1. It focuses on major accident hazards. It is common to see several safety programs and statistics with focus on personnel safety on drilling installations, which are talked about virtually on a daily basis. The reason for this could be that they are related to events which have higher probabilities of occurring. However, process safety – which is about low probability but significantly higher consequence events – tends to get sidelined in the process.

While the SCTA process can also be used to improve personnel safety and prevention of injuries, the resource-intensive nature of the study means that it is a better investment for prevention and mitigation of major accidents.

It can help in moving the focus equally over to the larger picture – matters that might be gradually building up toward a sudden release of hazard with catastrophic consequences. This also means that the organization can have a sharp focus on a manageable list of tasks while embarking on human factors integration.

2. It can shed light on the next steps an organization needs to take in its human factors integration journey. The SCTA process will identify significant human PIFs that are not in the optimal state for each safety-critical task. When a group of these tasks have been analyzed, a pattern may emerge that highlights significant areas of concern in the overall workplace, such as level of supervision, human-machine interface or training. Any identified pattern can then be explored and assessed further using other methods, such as workload assessments or control room ergonomics assessments.

What you can do

The IADC North Sea Chapter published “Human Factors – Guidance on MODU/MOU Safety Case Content” in July 2019. The document provides a well-rounded picture of the various aspects of human factors that a drilling contractor would need to consider.

Human Performance Oil & Gas also has a dedicated website with a multitude of tools, techniques and guidance to help duty holders begin to address human factors on their assets.

While it would be ideal for organizations to have in-house human factors capability as part of their office-based and onsite teams, this could take time to build. A short-term solution could be to begin by using specialist external consultants who would be in a position to guide and support by using their expertise, as well as present an unbiased view of where the organization currently stands. DC

Click here to visit the IADC North Sea Chapter resources page.