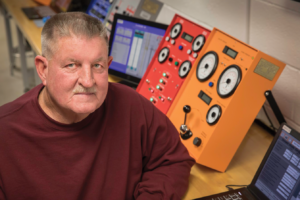

Randy Andres, ULL: Real-world field experience from instructors can set students a step ahead

By Sarah Junek, Associate Editor

You have to take his classes if you want to hear all of Randy Andres’ stories. He’s got a passion for well control and uses the classroom to share it as an instructor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (ULL). His stories, recounting his experiences from when he worked in the oilfield, could help to save your life, or someone else’s, the next time you’re out in the field.

Mr Andres grew up outside of El Paso, Texas, in the community of Tigua, the Native American tribe of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. He was used to hard work, ranching and riding fence lines as a teenager, so getting into oilfield work after graduating from high school in the late 1970s was an easy transition. He found himself working for Delta Drilling on various positions around the rig.

He also started taking classes at Texas A&M University on the advice of some of the professionals he worked with, but “I wasn’t in any hurry to graduate,” he said. “I was already making a grown man’s wages. I was a driller at 19, 20 years old.” The money was too good, so he took classes only part time.

After obtaining his petroleum engineering degree, Mr Andres went to work for Sperry Sun as a directional driller and engineer in its Bryan, Texas, yard. “At that time, directional drilling wasn’t like it is now. We didn’t have laptop computers and fancy downhole MWD tools. We actually had to do all the calculations.” At the time Sperry only hired engineers to do directional drilling.

By the 1990s, Mr Andres had joined Helmer Directional Drilling, based out of Youngsville, La. He remembers it as the most exciting and challenging time of his career. “We were doing work for all the big and small companies, and I was the only coordinator responsible for the operations of about nine rigs, running jobs in Texas, jobs in deepwater, jobs on the shelf and in Alabama,” he recalled. “That was a challenge because of the different drilling environments.”

One of the extended-reach wells he oversaw as coordinator during this time even set a world record, Mr Andres said. In 1994, McMoRan drilled five to six extended-reach wells in Main Pass 299 with 23,000- to 24,000-ft extended reach. “We achieved these wells with extensive well planning and execution, knowing torque and drag was going to be an issue,” he said. “That was really challenging and fun.”

The job was also extremely stressful, however, particularly the turnkey operations that the company took on – often simultaneously. He recalls juggling up to eight projects on any given day. “It was tough,” Mr Andres said.

The job took its toll, and he suffered a heart attack when he was only 40 years old. So when he got an offer in 2016 to teach petroleum engineering at ULL, it wasn’t too tough a decision to make. Still, Mr Andres emphasized that he doesn’t regret his years in the field and, in fact, believes that it set him up to be a better teacher in the classroom.

“A lot of educators, especially in petroleum engineering, don’t have any drilling experience at all,” he said. His field experience now allows him to give his students additional real-life context that other instructors may not be able to do. Mr Andres is also grateful for his connections in the industry, which has allowed him to take his students on tours of oil and gas facilities at least five times a semester. For example, after a classroom discussion on packers, he’ll take the students out to actually see the equipment.

Mr Andres said he also places emphasis on letting his students spend time in ULL’s simulator lab, where they can gain hands-on experience in performing everything from leak-off tests to kick prediction and detection to shut-in procedures. Simulator-based activities always lead to deeper discussions and better understanding of the methods, he asserted. Students in ULL’s petroleum engineering program spend up to 30% of class time in six operating labs.

In 2017, Mr Andres was instrumental in helping IADC set up one of its first student chapters at ULL, an initiative that aims to help interested students gain insights into the industry that they might not otherwise get in an academic setting. As part of his work as faculty liaison for the IADC student chapter at ULL, Mr Andres has helped to organize multiple tours of oil and gas facilities. He has also managed to take the students out to multiple driling rig tours.

With three years of experience now as a well control instructor, Mr Andres said he has set a goal for himself for 100% of his students to pass the introductory IADC WellSharp test. In fact, the final in his lab is a practice IADC WellSharp exam. ULL’s petroleum engineering school is also one of few academic institutions that have been accredited under WellSharp, for teaching at both the awareness and introductory levels.

It’s this kind of engagement and collaboration between schools and industry, he believes, that will pave the way to the future success of training next-generation engineers. DC