Oil and gas projects draw renewed interest from investors amid energy supply shortfall

Companies that can diversify, embrace transparency in sustainability and continue focus on capital discipline likely to be favored

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

Geopolitical events of the past year, and the resulting supply shortfall that has gripped much of the Western world, have placed energy security back in the forefront for a number of countries. The investor community has taken notice. While the “energy transition” continues – with governments around the world implementing policies that aim to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy – the process remains gradual.

The supply shortfall, on the other hand, is an immediate concern that could have long-term global impact. Investors have come to realize what operators and drillers have known all along: Oil and gas will continue to play a major role in the global energy mix for years to come.

“We are not at a point where renewables can completely fuel the needs of the world. It’s a long way to go,” said Seenu Akunuri, Energy, Utilities and Resources Deals Leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). “Even though certain investors might say they’re not going to focus on fossil fuels and will focus on renewables going forward, at the end of the day, when you look at global energy needs, for the next 10, 20, 30 years, worldwide consumption for hydrocarbons is going to continue.”

Still, the next few decades bring with them a ton of uncertainty. Just how big of a role will oil and gas play in the energy mix? What will companies need to do to draw interest from an investment community that, despite its recognition of the importance of oil and gas, is still under public pressure to move away from supporting the industry? For this story, DC spoke with analysts to gauge what the transition to net-zero could mean in the coming years.

Embracing sustainability

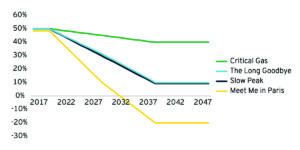

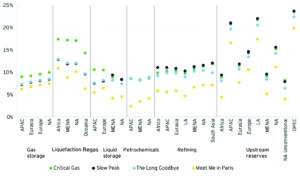

Pat Jelinek, Americas Oil and Gas Leader, US West Energy and Resources Market Segment Leader at Ernst & Young (EY), noted that the exact role of oil and gas in a low-carbon economy is uncertain. EY outlined four scenarios covering the range of possible scenarios for the energy transition, from a very gradual move away from hydrocarbons to the rapid adoption of renewables:

- Meet Me in Paris: Alternative energy quickly becomes cheap enough to displace existing energy infrastructure. In this scenario, peak oil has already happened in 2022, and demand will fall steadily after that. However, EY says this scenario is unlikely, as demand is still expected to increase next year. In fact, the US Energy Information Administration is forecasting global consumption of petroleum and liquid fuels to increase by 2 million bbl/day in 2023.

- Slow Peak: Peak oil does not happen until 2047, thanks to developing countries’ demand for petrochemicals, energy-intense industrial usage and aviation.

- Critical Gas: Oil demand peaks and trails off in 2037 as consumers migrate to electric vehicles. Capital moves toward gas-focused upstream and LNG assets.

- The Long Goodbye: Oil demand peaks in 2040 and continues at the same level through 2050, as oil consumption from existing vehicles, consumer inertia and continued growth in aviation and petrochemicals keep demand stable.

While these scenarios describe very different outcomes, they do share a few trends. For example, natural gas, in combination with renewables, will help drive decarbonization. This will create a significant upside for gas as a power-generation fuel, although projections for natural gas demand vary wildly. In the “Meet Me in Paris” scenario, gas demand grows by 42 billion cu ft/day between 2022 and 2050, a rate of 0.3% per year, compared with growth rates of 285 billion cu ft/day in “Long Goodbye” and 613 billion cu ft/day in “Critical Gas.”

It’s important to note that investors should see positive returns on their oil and gas projects regardless of the energy transition scenario, Mr Jelinek said. This is because, even after peak oil, there will still be demand for oil and gas. The challenge is that the returns will not always be stable and predictable, and the pressure on governments around the world to reduce fossil fuel usage introduces geopolitical risk.

There are some actions that the industry can take to help investors overcome their hesitation. One is a continued focus on capital discipline and on returning cash to shareholders instead of chasing growth. This has already been ongoing since the 2020 downturn, and, if continued, could help to reassure investors.

Additionally, increasing transparency around emissions data and sustainability efforts can be advantageous. In a 2022 study, EY reported that 82% of oil and gas companies published a sustainability or ESG report aligned to the GRI, SASB or TCFD frameworks in 2021, compared with just 76% in 2020.

This increase in sustainability reporting has made investors “more educated and comfortable” about the oil and gas industry’s pledges toward the low-carbon future, Mr Jelinek said, because they can see the progress being made. However, he noted that companies will need to improve the quality of their sustainability reports in order to maximize their value. In particular, EY noted in its report that only 26% of oil and gas companies include third-party assurance on ESG metrics in their sustainability reports.

There’s also still a lack of reporting on Scope 3 emissions. EY pointed out that oil and gas companies primarily report on direct emissions from company-owned and controlled resources (Scope 1) and indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy from a utility provider (Scope 2). Only 33% of companies in the EY survey reported Scope 3 emissions, the indirect emissions that occur in the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream.

This can be problematic because Scope 3 emission sources typically represent the majority of a company’s GHG emissions, but they are also the most difficult to measure and report because they cover sources that are not directly under a company’s control. “Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions are manageable,” Mr Jelinek said.

“Now, the lift is enormous when you think about some of the complexity and the breadth of the operations needed to reduce those emissions, as well as the age of some of the assets that exist in the industry. But accurately reporting on Scope 3 emissions is getting into areas that can be outside of the control of the operators, or even the investors. You’re getting into areas where there aren’t technical reporting standards.”

As the energy transition further progresses, sustainability reporting will likely become a must-have, rather than a nice-to-have, in order for the industry to secure funding for new projects. In March 2022, the US Securities and Exchange Commission proposed rule changes that would require companies to include climate-related disclosures in their registration statements. Under the new rules, which could go into effect for FY 2023, companies would be required to disclose information about:

- Its governance of climate-related risks and relevant risk management processes;

- How climate-related risks have had or are likely to have a material impact on their business in the short-term and long-term future;

- How climate-related risks have affected or are likely to affect the company’s strategy, business model and outlook; and

- The impact of climate-related events (severe weather events and other natural conditions) and energy transition activities on the line items of its consolidated financial statements.

The proposed rules would require companies to report Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Scope 3 emissions would be voluntary unless a company has set an emissions reduction target that specifically includes them.

Another pressing challenge is the exodus of labor, Mr Jelinek said. The frequency of downturns and perception issues among younger workers are both contributing factors, but the latter is especially concerning, he noted. In a 2020 EY study on the energy workforce, 92% of oil and gas executives surveyed said they believe the ability to re-skill their workforce will determine their company’s success in the near-term future. However, only 9% felt strongly that they have a “robust plan” in place to do so, and just 3% felt strongly that their organization is adept at re-skilling their workforce.

While executives surveyed were bullish on their ability to fill skills gaps through hiring, this confidence is a double-edged sword. The fact that an increasing number of new graduates and existing workers are developing these in-demand skills reflects a strong growing demand for those skills across multiple industries, Mr Jelinek said. This means the oil and gas sector will face increasing competition for talent, at the same time that a negative industry image drives young workers elsewhere.

To address this challenge, Mr Jelinek urged the industry to vigorously promote its long-term commitment to sustainability. “I think there’s a realization now within the industry that you need to show people how this industry is a humanitarian necessity. People need energy, and they’re seeing that this industry is actually contributing to the energy transition,” he said.

Drawing investor interest in a divided future

In its 2022 World Energy Investment Report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) noted that the average level of investment in oil and gas projects is expected to hit $720 billion this year, a 10% increase over 2021 levels. This figure is higher than what the IEA had projected for year-end 2022 ($550 billion) and significantly higher than its projection for what needs to be invested in the latter half of this decade ($340 billion). Both projections were made under the IEA’s NZE (net-zero emissions by 2050) scenario.

The juxtaposition of actual investment levels with analyst projections raises the question of whether the current energy security crisis will open up opportunities for greater long-term investment in oil and gas. Mr Akunuri described this question as essentially balancing between different visions of the future.

“Companies are going to be much more focused on not only the return and the risk, but also from a longer-term perspective, as they are going to have to decide what their portfolios are going to look like 10, 20, 30 years from now. They have to make investments based on that. Some of the projects under consideration alleviate short-term issues, some are being made toward a future where everything is renewable, and some are more of a balancing act,” he said.

Some regional variations in renewable investments can be seen. From 2010 to 2022, countries with more advanced economies grew its capital spending on renewables and electricity grids by $50 billion, according to the IEA. While emerging economies saw this spending increase by around $1 trillion, China alone accounted for approximately 90% of that. Other emerging economies only saw their spending on renewables grow by $10 billion, but stayed resilient on their investments into fossil fuels, averaging around 30% of total power investments. Advanced economies, as well as China, averaged less than 10% investment in fossil fuels in that time period.

Mr Akunuri noted that fossil fuels will continue to remain vital to developing countries, which will require significant electricity as they industrialize. “In my view, with fossil fuels, the returns are faster and they come sooner than renewables. When it comes to building clean energy like solar farms or wind turbines, that still takes a lot of investment, and some of these developing countries don’t have the infrastructure or the cash to build those things yet,” Mr Akunuri said.

As investments into both fossil fuels and renewables continue in the coming decades, it’s becoming clear that the market will reward companies that diversify. In a report issued this year (“Shifting Grounds: The Future of Global Energy Systems and the Infrastructure Challenge”), PwC noted that energy transition and wider technological changes are creating opportunities for companies to capture new sources of value, as previously separate value chains are becoming increasingly interdependent. This trend is leading oil and gas companies to develop collaborations down the value chain.

The PwC report mentioned the ongoing work on hydrogen development, but Mr Akunuri also cited the industry’s work with battery energy storage systems and carbon capture and storage as examples of long-term renewable investments that will help companies in the oil and gas space to stand out from their peers.

“You can’t just be at status quo,” he said. “Even though we’ve had a couple of downturns recently, the industry has gone through cycles before and it will in the future. At the current commodity price, if you’re cash flow positive, you need to be making investments with a view towards the future and a balanced portfolio. That’s what investors want to see.” DC