Offshore industry, beset by project deferrals, rig contract terminations, looks to standardization, reliability for long-term cost reductions

Deepwater sector has remained more resilient than shallow water so far, but sustained low oil prices, oversupplied rig market spell more trouble ahead

By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

Throughout 2015, the industry had remained hopeful that the downturn would be short-lived. During the summer, when oil prices temporarily buoyed, some believed that signaled that the market was on its way up again. However, prices trended downward after that, dipping below $40/bbl in the last quarter of the year. Many finally accepted the reality that this downturn would be lower for longer.

“It really took prices taking that nosedive down below $40 in the later part of the fall and into the winter that really made people realize that this was serious,” Robin Mann, Oil & Gas Resource Evaluation & Advisory Leader for Deloitte, said. For the offshore industry, this means that 2016 will be another rough year, as dayrates and rig counts continue to slide and operators defer exploration and development projects. “If a project is not in the works and is not under way where they’ve already spent a significant amount of money and they can postpone, they will postpone,” Mr Mann said.

A total of 29 deepwater projects have been deferred since late 2014, according to a recent report by Wood Mackenzie. None of these projects had received a final investment decision (FID). One prominent project that has been delayed is Shell’s Bonga South West offshore Nigeria. In the company’s Q4 2015 earnings call, it was announced that the FID for this project would be pushed into 2017. Shallow-water projects are also facing delays, such as Statoil’s Mariner field on the UK Continental Shelf. The company announced in its Q3 2015 results that the start-up date for Mariner would be pushed to the second half of 2018.

Overall, companies seem to be focusing efforts on areas with existing infrastructure and where they have already seen positive operational results. “They’re going to look at the ones that make the most sense,” Mr Mann said. “They will concentrate on those and move away from the other ones if they can. I think you’ll see companies concentrate their efforts into one or two offshore areas.” For smaller operators that are active in only one geographical region, they may narrow their focus to just one or two fields, he added.

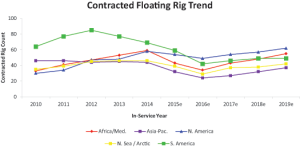

So far, shallow water has suffered a steeper fall than deepwater has, a trend that is continuing in 2016. Part of the reason is that jackups have shorter contracts, making it easier for operators to let those rigs go as they roll off contracts. However, Mr Mann explained, because deepwater projects are so much more expensive, the companies that invest in them tend to have stronger balance sheets and, thus, tend to be better positioned to endure a difficult market.

At the same time, the jackup market is a lot more oversupplied than the floating rig market. This means more competition for the few contracts that are still being signed, said Andrew Meyers, Manager at Douglas-Westwood. “There are over 100 jackups still under construction, although a few orders have been canceled recently, and only a handful have contracts,” he said. “You’re not going to be able to retire enough rigs to balance the market very quickly in shallow water.”

On the floater side, while this sector of the market was initially protected by their longer-term contracts, that protection is starting to fade. “About 70% of contracts that are for $500,000/day or higher are going to roll off by the end of 2017,” Mr Meyers said. “With that much supply available, you would expect dayrates to fall pretty steeply.”

Further, several floater contracts have been canceled over the past year, hitting every major drilling market around the world. In March 2015, BP canceled contracts for two ultra-deepwater drillships in the Gulf of Mexico – Seadrill’s West Sirius and Ensco’s DS-4. The contract for the West Sirius was supposed to run through July 2017, while the DS-4 was supposed to work through July 2016. Late last year, Statoil canceled a contract for Songa Offshore’s Songa Trym semisubmersible, which was working in the North Sea, four months early. The operator also canceled its contract for the COSL Innovator semisubmersible.

Offshore West Africa, Total announced in February that it was terminating its contract for the Ocean Rig Apollo drillship, which had been contracted through March 2018. The same month, ExxonMobil terminated its contract for the Transocean GSF Development Driller 1, which had been due to expire in June. The rig was working offshore Angola.

Looking to the next few years, Douglas-Westwood is forecasting deepwater spending to total $137 billion between 2016-2020 – this reflects a 35% reduction from its 2015 forecast. Similarly, the firm has lowered its forecast for the number of projects that are expected to be installed by 2020 – from 210 to 118.

Less deepwater work to go around

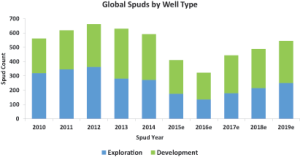

The number of deepwater exploration and development wells drilled decreased from 591 in 2014 to 410 in 2015, according to Quest Offshore Resources, which tracks deepwater activity and trends. In 2016, the company expects to see fewer than 300 deepwater wells drilled.

Looking specifically at exploration, a total of 175 wells were drilled last year, a 36% decrease from the year before. Quest is forecasting another 35% drop for 2016. “From 2010 to 2012, exploration wells drilled annually averaged between 325 to 360,” said Leslie Cook, Quest Senior Research Consultant for Deepwater Drilling, said. “We’re not forecasting anything near that over the next five years.”

On the development side, 235 deepwater wells were drilled in 2015, down by 25% from 318 in 2014.

With fewer wells being drilled, marketed utilization for deepwater rigs worldwide has fallen to 70%. The fact that 42 such units will roll off contract before the end of the year will likely push that number down further still. At this time, Quest also expects four newbuild drillships to enter the global fleet in 2016. Diamond Offshore is expected to take delivery of a semisubmersible to work for BP in Australia; Songa recently took delivery of the last of four Cat-D moored harsh-environment semisubmersibles for Statoil in the North Sea; and Transocean will add two new working drillships to its Gulf of Mexico fleet for Chevron and Shell.

As new rigs continue to enter the market, drilling contractors will need to become much more aggressive on rig retirements, Ms Cook said. The industry retired 42 floating rigs in 2015. As of March 2016, four more retirements had been announced. Yet, more are still needed. There are approximately 45 rigs that are over 30 years old and stacked, and they are unlikely to find work again, she said. “These are rigs that may never go back to work because by the time the market gets strong enough for them to even become competitive, they’re going to be over 40-years-old. They’re dying on the vine.”

Even the sixth- and seventh-generation rigs will no longer see anything close to the $500,000 dayrates they had been enjoying. “If they’re getting renewed or getting follow-on work, it’s for closer to $350,000/day,” Ms Cook said. The good news, however, is that rates are likely near bottom. When operators feel that rig rates are the lowest they’re likely to go, some might opt to begin securing long-term contracts again. “When the market gets down to a certain cost point, it’s advantageous to an operator to start looking at certain key assets that maybe they don’t need today but that they’re going to need in 2018,” she said. “We think that’s maybe going to come into play in 2017.”

Difficult economics

Globally, deepwater activity has remained strongest in the Gulf of Mexico. “A lot of the operators there have positions in Africa and Brazil, and they’ve cut back in those areas,” Ms Cook said. “But they’re concentrating on the Gulf.” One reason is because the Gulf has been able to remain more economic at a lower oil price. Projects in more developed areas, like the Green and Mississippi Canyons, have existing production infrastructure, making some projects economic at $30-$50 oil, Ms Cook said.

The Lower Tertiary, however, has proven more challenging, with higher temperatures, higher pressures and less infrastructure. This means companies are losing money even with oil prices between $50-60, she added.

Deepwater drilling offshore Africa will require an oil price above $70 to return to anything near 2012-2013 activity levels, Quest data shows. Major factors contributing to the region’s high costs include strict local content requirements established by regional governments and logistics costs around getting equipment in and out of country. Security in the region is also a concern, requiring significant investments for office facilities and employee housing, along with the rigs themselves. “Those are cost factors that have really hurt African activity tremendously through this downturn,” Ms Cook said.

In Brazil, it’s the political climate that is playing a big role in reduced deepwater activity. “The real problem is that the epidemic of corporate corruption has caught up to them, and companies are playing a ‘one foot in, one foot out’ game right now,” Ms Cook said. “The Car Wash investigation has brought the oil giant and the country to its knees. Companies don’t want to abandon Brazil because the long-term prize is too big, but they also don’t want to get caught up in the bribery scandals.” However, she added, “we cannot underestimate the desire among IOCs to take a larger stake in the pre-salt prize. Once the Brazilian government makes the necessary changes to licensing and lowering local content, the offshore market in the country will be back with a vengeance.”

Over in the North Sea, although politically stable, the challenges and costs of drilling in a harsh environment has led rig count to fall by approximately a third during this downturn, said Sean Shafer, Quest’s Head of Consulting. “It’s a very mature region, as well,” he added. “The fields that are left, apart from some of the frontier areas, are typically smaller, with lower returns.”

Labor costs are also higher, particularly in the UK and Norway, although the tax regime in some countries are now becoming more friendly to the oil and gas industry. The prime example is the UK’s Petroleum Revenue Tax, which was reduced from 50% to 35% in early 2015. “That might make things a little more attractive going forward,” Mr Shafer said.

In all regions, brownfield projects, where operators are able to tie new projects into existing infrastructure, are more likely to go forward than developing brand-new fields. “That can easily shift breakeven prices by $30/bbl,” Mr Shafer said. For brownfield projects, breakevens tend to range from $20-$50/bbl whereas breakevens for greenfield projects range from $45-$90/bbl.

Simple vs complex

A big part of the cost equation in the offshore industry can be attributed to increasingly complex and expensive technologies. Over the past decade, the offshore sector had allowed a great deal of complexity to creep into equipment, rig and production facility designs. For example, FPSOs have become much larger and more complex even though they’re not actually producing at a much higher rate than before, Mr Shafer said, adding that they also cost 200% more than they did in the early 2000s.

Some cost inflation has been the result of legitimately improved technology, or perhaps changes that were necessary to enhance safety. In the US Gulf of Mexico, for example, many changes were made to drilling rigs and floating production systems after Macondo and in response to several damaging hurricanes. However, many changes have also been made that don’t necessarily add value or make anyone safer, he asserted. “There’s this love of complexity in the deepwater industry,” Mr Shafer said. “Some of it is required to meet technological requirements, but a lot of it is not.”

He asserts that the main reason for such high levels of complexity is risk aversion – in ways that don’t always make sense. “They’ve engineered some of these risks out without taking into account the potential costs of engineering the risk out versus the potential cost if something were to go wrong.”

For example, there has been an increased use of corrosion-resistant alloys in production tubing. Utilizing these alloys makes the tubing much more expensive, but the risk of corrosion in any given downhole environment and the associated costs could be relatively low. “If there’s a 2% risk of failure, is it worth paying double or triple the amount for materials?” Mr Shafer questioned.

In response to growing complexity, more companies are now looking toward standardization and simplification, “both as something that can speed up projects and something that can decrease the complexity of the supply chain,” Mr Shafer said. In the past, it wasn’t uncommon for companies to pick the most expensive and complicated version of a particular piece of equipment or system as their standard, when a less expensive, less high-end version of the equipment would suffice for most of their projects. “Before, what they were doing was standardizing on the highest-end equipment,” he said. “Now they’re realizing that if they standardize on the most complex subsea tree they’re ever going to use, it’s not going to be effective for their whole portfolio.”

The need to standardize and simplify was reinforced by a survey DNV-GL published in March. In this survey, 74% of respondents from across the industry reported that their companies had achieved their target cost reductions in 2015. However, Cathrine Torp, VP Communications Director for DNV-GL, explained that much of the reductions operators achieved in 2015 came from CAPEX reductions, reducing headcount and asking for lower rates – measures that don’t lead to long-term cost improvement. “To reduce costs long term, we need to simplify and standardize our requirements,” she said.

To demonstrate the lack of standardization within the offshore industry, she pointed to the color of subsea pipes. Different companies may request a pipe that is a slightly different shade of yellow than the pipes an equipment supplier might generally provide. For the supplier, this could mean having to keep 15 varieties of the same piece of equipment in their warehouse. “If a long chain of suppliers can use the same components for all operators globally, that’s less costly than making something specific for each individual operator.”

To counter this trend, the offshore drilling industry could look to the maritime industry, said Per Jahre-Nilsen, Business Development Leader, Drilling & Well at DNV-GL. The maritime industry has global standards for each particular type of vessel or ship, rather than many sets of individual standards or requirements that vary by company. “The standards are harmonized, and there’s a track record showing that they work,” he said.

Earlier in his career, Mr Jahre-Nilsen was working for a company that provided equipment for the offshore and maritime industries when an order came in for a 2-megawatt electrical generator for a drilling vessel. “There were so many add-ons that came into the picture,” he recalled. “All these tiny, small things that really increased the cost of this product. The price tag was five or six times higher than is typical.”

In many cases, he said, companies tend to add complexity without adding value. It could be they want to ensure regulatory compliance, but it could also be due to competitiveness – a desire to be best-in-class. “You’re afraid of doing something wrong, so you add on and you add on and you add on, instead of asking the question ‘What is good enough?’ ” he said.

Another driver of complexity is documentation. In 2012, for example, approximately 10,000 documents were needed to install a basic subsea system, Ms Torp said. By 2015, that number had increased to 40,000.

To minimize documentation and the associated time required for review, DNV-GL started a joint industry project in 2014 aimed at the documentation-heavy subsea sector. Participants include Aker Subsea, Kongsberg Oil and Gas Technologies, Statoil and OneSubsea. The goal is to get operators, contractors and suppliers to agree upon a typical set of subsea systems and functions and its required set of minimum documentation. This could result in reduced project lead time. The JIP participants expect to publish a Recommended Practice on subsea documentation by Q3 2016.

Ensuring reliability

For OEMs, the most important role they can play in operators’ and drilling contractors’ cost reduction strategies is to ensure equipment reliability, said Bob Judge, Director of Product Management at GE Oil & Gas. “We’ve got to minimize the number of days that a rig isn’t drilling a well,” he said. “The best way we can do that is to ensure equipment is available when it’s called upon to do its job.”

On drilling rigs, data suggests the No. 1 cause of downtime is the BOP control systems. Industry practices require that two pods on the subsea portion of the control system be operational in order for a rig to drill ahead. If a pod fails, the general practice is to retrieve the BOP stack and fix the pod, which can lead to anywhere from five days to 14 days of downtime.

In October 2015, GE released its 20ksi drilling system, including the SeaPrime I MUX BOP Control System, which is able restore functionality even after components have failed. The system isolates and then reroutes critical hydraulic functions while remaining subsea. According to GE, it can deliver three times more availability than a traditional MUX pod system. “We’ve got a system that can suffer a fault without requiring a stack pull,” Mr Judge said. Instead, the system can be reconfigured from the surface in hours, rather than days.

The SeaPrime system utilizes what GE calls smart redundancy. The system has the required two pods, but rather than including a redundant component for every part of the stack, only critical components have a redundant element. “If one of those were to fail, I have redundancy for that one in a certain fault-tolerant way that I can then activate to recover that function.”

The amount of tubing inside the subsea pods has been reduced by 40% in the system. When the pods are undergoing surface maintenance, this allows the maintenance crew to access the components they need to work on more quickly and easily. It also reduces the likelihood of an error during the maintenance process. “If I have 40% less tubing, that’s a 40% less chance that one gets assembled incorrectly,” Mr Judge said.

Meeting with drilling contractors before a drilling program begins has also helped shorten the time required for performing between-well maintenance, Mr Judge said. “What we have found is if we can be involved in those conversations, we’ve been able to significantly reduce the number of days required just by being in the room and having a voice at the table as maintenance activities are planned.” In one case, this sort of collaboration reduced the time a drilling contractor spent performing between-well maintenance from 12 days to four, according to GE.

To minimize engineering costs and lead times, GE also looks to standardization. Last year, the company reduced the lead time for its annular BOP line by providing options for nine variations of the equipment that are considered standard. By avoiding customized solutions, lead time for this equipment has been reduced from 52 weeks to 20 weeks. “We’ve had customers who previously didn’t order these because of our lead time come back to us and start ordering,” Mr Judge said.

Equipment providers, drilling contractors and operators have all contributed to the industry’s drift toward high levels of customization and complexity over the years, Mr Judge said. “We, as an industry, have encouraged that behavior because we accommodated it for a long time. The industry asked, we put an invoice in front of them, and they paid it.” However, in this environment, GE has seen customers express a willingness to seek out and adopt standard solutions. “We are starting to have those kinds of conversations about what can be done to reduce costs other than just reducing prices.” DC