Norwegian minister: Climate change, greater access, Russia driving Arctic development

By Katie Mazerov, contributing editor

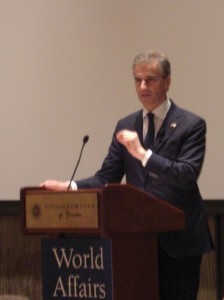

The Arctic could hold the answer to energy security and independence as the world continues to need fossil fuels, a high-level Norwegian official told a gathering of industry executives at the Petroleum Club of Houston on 6 January. The event was sponsored by the World Affairs Council of Houston.

In the address, “Melting Ice, Moving Frontiers: The Challenge of Energy Development in the Arctic/High North,” Norwegian Foreign Affairs Minister Jonas Gahr Støre said climate change, expanding sea routes and Russia are three main drivers of change for opening up opportunities in the Arctic. Those forces also must foster international cooperation among the Arctic coastal states – Norway, the US, Canada, Denmark (Greenland) and Russia – to solve boundary disputes, develop uniform environmental measures and manage energy independence, he said.

“At a time when countries and industries are looking to the east and the south – China, Indonesia, India, South Africa and Brazil – they are also looking to the north,” Mr Støre said. “This is a great time to focus on the opportunities that exist in the Arctic, which may hold up to 25% of the world’s untapped resources, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS).”

As the world’s second-largest exporter of natural gas and the sixth-largest exporter of oil, Norway is a “small country with a big commodity” that expects to maintain its already-dominant position in global hydrocarbon production, Mr Støre said, noting last year’s two significant oil discoveries, including one in the Barents Sea. The country also is able to share its knowledge about strong environmental stewardship. “In Norway, there is a social contract between the government, the people and industry that hydrocarbon production is accepted and is moving north. But, it must go hand-in-hand with major and dedicated efforts to develop groundbreaking technology to deal with climate change,” he said.

Climate is warming

Acknowledging that climate change is a real phenomenon can serve to enhance Arctic exploration and production, not close it down, he maintains. “Make no mistake, the climate is warming, as evidenced by the changing environment in the High North. A consequence of that shift is that sea routes are opening up. We can now sail the Northwest and Northeast passages and around the polar basins. This transformation of shipping routes will bring greater access to resources in the region.”

Russia, he continued, is a nation in transition that has huge resource potential; it also shares a border with Norway. A 40-year-old border dispute involving 175,000 km of overlapping boundaries between the two countries became a landmark case for establishing a legal foundation to extend the United Nations Law of the Sea to Arctic waters.

Using the Law of the Sea as a basis for negotiation, Norway and Russia last year signed a historic treaty defining their boundaries as they relate to both energy and commercial fishing interests. “This served as an important signal to the rest of the Arctic states that these issues can be settled through negotiation,” Mr Støre said.

Energy, he said, is one of seven key “dimensions” in defining how Norway sees the Arctic developing over the next 20 years. The opening up of shipping routes, the emergence of Norway as a major research and development hub for studying such issues as climate change, pioneering work on integrated marine management and greater recognition of the Arctic Council as the circum-polar organization to facilitate ongoing cooperation and treaty negotiations, will help facilitate Arctic hydrocarbon production.

“The Russian petroleum sector is increasingly moving offshore,” Mr Støre said. “The Barents Sea will likely be an important energy province.” Concerns about the 2009 Russian oil spill signal the need to raise the level of common environmental standards, he said. “With Russia, we need to encourage transparency. The rules themselves are stringent, but we need to draw Russia into the international forum and hold it accountable.”

Improving environmental standards while making energy available requires “sophisticated, democratic political decision-making,” he said. “If this is going to work, if there is going to be a new energy region in Europe that is modern and prosperous with great potential, industry must be part of a joint venture in developing new technology to master climate change.”