HSE&T Corner

Government mandates, industry innovation drive change in rig-site fall protection

By Steve Kosch, 3M

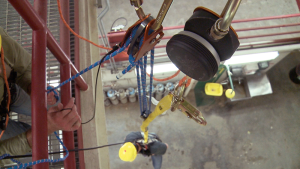

The hazards associated with working high above the ground on a drilling rig presents significant safety concerns, from the potential of a well blowout to the possibility of a worker losing his or her footing and falling.

API Recommended Practice 54 and its subsection 6.10 regarding auxiliary escape address these concerns. It requires a “specially rigged and securely anchored escape line” that provides ready and convenient escape from a worker’s platform.

The most commonly used device for such escape is a manually operated escape device. The device consists of a line, which is attached to the derrick or mast and anchored to the ground at an angle, as well as an escape trolley with a hand brake that workers use to escape the rig and descend to the ground at a speed dependent upon manual brake control. If the worker lets go of the brake, they descend down the line as fast as gravity takes them, creating a potentially unsafe descent rate.

Land-based oil and gas operations have relied on this escape device for decades. In comparison with other escape system technologies that are available today, however, this device can be considered to be antiquated and even unsafe. The device, for example, is free-riding and is not designed with a lanyard to securely attach the worker to the device.

The potential for improper rigging also presents potential safety risks.

Many work sites don’t even have rig workers conduct hands-on training with the device out of fear for the workers’ safety. This could pose additional safety risk during an emergency situation when the worker’s life may depend on the device and his or her knowledge of how to properly use it is minimal.

Now, a combination of government mandates and industry innovation are helping to drive change in fall protection.

Wyoming Leads the Way

Wyoming is a top-10 oil producer in the United States. The state’s annual oil production exceeded 100 million bbl for several years in the 1970s and 1980s, but production had tapered off to around 50 million to 55 million bbl/year for much of the 2000s. With the introduction of new technology and new wells, the state exceeded 60 million bbl in 2013 for the first time in nearly 15 years, according to data from the US Energy Information Administration.

The Wyoming State Geological Survey (WSGS) estimated in its 2014 oil and gas summary report that Wyoming’s oil production will exceed 66 million bbl in 2014. The WSGS expects that figure to continue trending upward in the coming years as various projects in the permitting stage have the potential to add more than 23,000 wells between 2014 and 2018.

Amid this boom, Wyoming has taken a renewed look at safety requirements for oil and gas workers. Specifically, Wyoming lawmakers are implementing a ban on the use of manual-brake escape systems for escape from oil and gas rigs.

The revised law removes language requiring “an approved safety personnel carrier with a brake” for controlling descent. It will instead require that “an approved emergency descent device shall be installed on the escape line and kept at the derrickman’s working platform.” The emergency-descent device and escape line must be inspected prior to each trip, and employers must provide workers with training for its application and use.

The Wyoming law will be the first of its kind when it takes effect in 2016 – fitting for a state that describes itself as being “like no place on earth.”

The law represents a significant shift forward in helping protect workers in simulated and real escape procedures. But employers outside of Wyoming need not wait for their state governments to follow suit – emergency-descent devices that are simpler, lighter and more versatile already exist.

Device Alternatives

Compact, modern descent systems can provide an ideal alternative to the manually operated devices used in most oil and gas operations. These more portable devices can provide automatic-descent capabilities with the twist of a dial to stop, start or adjust the speed of a worker’s descent, giving workers added confidence.

Such devices weigh a fraction of traditional manual-control escape devices, making them easier for workers to carry when working at heights. Whereas concerns about the safety of emergency escape devices used on rigs today might prohibit training, the added confidence provided by modern systems can be an enabling force to conduct training and ensure workers are familiar with the system and the escape process.

Certain compact descent systems also offer more versatility than traditional devices and can support assisted rescue operations. Remember that falls aren’t the only hazard when working at heights. Workers can also become overwhelmed and incapacitated due to strong fumes, heat exhaustion, blunt-force trauma and electrical shock. Even a seemingly minor bee sting can send a worker into anaphylactic shock, rendering him or her unable to perform a self-rescue and, thus, requiring an assisted rescue.

When evaluating potential replacements for a manual-control escape device, these general criteria can help guide companies through the selection process:

• Speed. Descent speed can be vital during a blowout or other critical event. Some escape and rescue devices offer a controlled descent rate of up to 3 m/sec (9.8 ft/sec). The ability to rescue multiple workers using one device can also expedite rescue time when every second counts.

• Application Suitability. Flame-resistant escape lines are essential in oil and gas environments where the potential for fire always exists. Some modern systems use advanced materials for ropes that are rated for resistance in temperatures of up to 925°F.

• Ease of use. Many devices must be specially reconfigured for a large or small person. This adds complexity to the rescue process and requires a higher level of user training. Consider using pre-rigged systems that can be more easily configured regardless of how heavy the person might be.

• Training. OSHA and ANSI Z359.2 require annual training at a minimum, but both encourage more rescue training. Look for devices that don’t need to be sent off for recertification after each use. This can allow repeated use of the equipment for training purposes and help better prepare workers for an actual emergency.

• Certification. The equipment should comply with the most stringent requirements for worker escape – such as Wyoming’s law replacing API RP 54. Equipment should also comply with ANSI Z359.4, which covers technical requirements and testing procedures for rescue descent devices, harnesses, ropes and other equipment.

To ensure the drilling industry continues on to improve its safety performance, employees should be properly trained for quick escapes or rescues. Replacing the emergency-escape devices of yesterday with a more compact system that provides automatic-descent capabilities can instill greater confidence in workers regarding their safety, support more frequent training, and provide greater versatility in rescue and safety operations.