By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

Ensuring a safe workplace is a core priority in the oil and gas industry, but health hazards typically receive less attention than safety hazards do, Fitria Nubaidah, Industrial Hygienist at ApexIndo, said at the 2016 IADC Drilling HSE&T Asia Pacific Conference, held in Kuala Lumpur on 24-25 February. In part, this is because the effects of a health problem caused by workplace conditions may not manifest right away. This makes it difficult to determine cause and effect, while the consequences of a safety failure are generally immediate and easy to see.

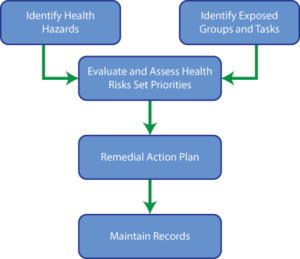

“It is important for companies to start adopting a proactive approach to health risk management. Our workforce does not only deserve a safe working environment but also a healthy one,” Ms Nubaidah said. Using a health risk assessment (HRA) allows companies to identify, assess, control and record workplace health hazards.

The first step in an HRA is to identify health hazards and which employees are exposed to these hazards. This can be done through desktop analysis, walk-through survey and measurement survey. A desktop analysis is essentially a document review. Examining incident reports, incidences of occupational illnesses, sickness/absentee records and material safety data sheets can provide insight to health hazards.

Another method for identifying risk is the walkthrough survey, which involves touring a work site and observing potential hazards. During this survey, the individual or individuals performing the survey should look for working conditions that put employees in an environment where there is extreme temperature, excessive noise, radiation or dangerous chemicals. The survey should also consider how the culture, workload and other intangible factors could impact an employee’s health or well-being.

A measurement survey attempts to quantify hazards. For example, while excessive noise may be observed during a walkthrough survey, a sound level meter could measure the noise level where crews are working. Surveying personnel about their working environments and potential hazards could also help companies understand and quantify health risks.

After identifying the risks, the next step in the HRA is to assess these risks. All risks should be considered using a health risk assessment matrix, which considers the consequences of a particular health hazard, the probability that crew will be exposed to that risk, how long personnel may have to be exposed and uncertainty around the risk. The combination of these factors allows a risk rating to be established.

Next, the employee’s exposure to health hazards must be managed. “Regarding the remedial action plan, it’s almost the same as with safety,” Ms Nubaidah said. “We use the hierarchy of control that starts with elimination and ends with personal protective equipment (PPE).”

To illustrate this hierarchy, Ms Nubaidah pointed to the working conditions around the shale shakers and mud pit on a rig. Particularly when oil-based mud is used, employees working in these areas could be exposed to hazardous fumes. The first level in the control hierarchy is elimination. Avoiding the use of an oil-based mud would remove the hazard. If that is not possible, engineering control can be considered. In this case, ensuring there is good ventilation around the mud pit or shale shakers could help manage the risk of exposure to fumes.

The next level is administration. A company could dictate a maximum amount of time crews can spend near the shaker or the mud pit to minimize their exposure. Finally, at the bottom of the hierarchy is PPE. The crew would be provided with a mask to protect them from chemical or fume inhalation. “When we set up PPE, we should ensure that the PPE we choose is proper for the hazard in the area,” Ms Nubaidah said. The final step in an HRA is record-keeping and communication. “One of the important things is that we need to communicate the results from the HRA, so we can improve the knowledge and awareness of our crew related to health hazards and risks,” she said. DC