Deepwater leveling out but likely to stay flat through 2018

Current focus on short term results in more early rig contract cancellations, cold stackings, but long-term optimism remains as deepwater is still expected to play crucial role in global energy supply

By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

- Deepwater rig utilization is expected to fall by approximately 5% in 2017, then remain flat in 2018.

- Golden Triangle regions accounted for 75% of early rig contract terminations in 2016.

- Between US Gulf and West Africa, operators appear to be prioritizing the former due to the higher costs of drilling in Africa.

- Some deepwater rigs are now working at dayrates in the high $100,000s, which is close to or beneath breakeven levels.

When oil prices began falling in 2014, the industry’s collective hope was that they wouldn’t stay down for long. However, the industry is now closing out its second full year in a massive downturn, and there’s not much good news on the horizon for offshore drillers. Over the past two years, many of their older assets have been retired – 10 drillships, 52 semis and 27 jackups since July 2014, according to IHS. But that hasn’t been enough. The offshore rig market is still out of balance.

“The number of rigs being retired is not enough to reduce the overhang of available rigs,” said Tom Kellock, Head of Offshore Rig Consulting for IHS. As of October, total under-contract utilization for the main types of offshore rigs was sitting at 53%, and that is not expected to budge much over the coming year. There is simply not enough work to increase utilization, Mr Kellock said.

For rigs that are finding work, in most cases they’re not getting long-term contracts like they used to. “We are seeing a number of short-term contracts popping up, mostly where companies either have an obligation to drill a well, or they’re taking advantage of the low dayrates to do work that would have to be done in the future, like plug and abandonment work,” Mr Kellock said.

Compared with deepwater, shallow water is faring slightly better because there are more lower-cost and short-term projects that can be performed. “Deepwater tends to be the larger, more expensive projects. Until the oil price changes and cash flow for operators starts to rise again, they’re going to be very careful about implementing larger projects with higher costs.”

Such deferrals of exploration and development in deepwater may make financial sense now – clearly it is what shareholders want – but the industry is likely to regret it down the road, said Chris Beckett, CEO of Pacific Drilling. “Unfortunately, in a downturn like this, there tends to be an excessive focus on the short term,” he said. “I just encourage everyone to start thinking about what’s going to happen by the end of the decade if we don’t get the industry back to work very quickly.”

The industry has been curtailing not only its exploration and development drilling but also its workovers and in-field drilling. This means that much of the oil that’s being used isn’t being replaced. For the short term, this doesn’t present a significant problem due to the excess oil sitting in storage. But “when you look at that on a forward-looking basis, our estimate is that by the end of the decade, we’re going to be potentially as much as 10 million barrels short of supply,” Mr Beckett said. “So I’m very bullish on the fact that there’s going to be a lot of demand for deepwater drilling as a key part of the oil supply picture.”

Flattening out

As of September, the marketed utilization rate for deepwater rigs was 65% and total utilization was 50%, according to Quest Offshore, which was recently acquired by Wood Mackenzie. Those numbers are bleak, but the silver lining is that utilization is not expected to fall much further, said Leslie Cook, Senior Research Manager for Quest Offshore. “We really do feel that 2017 is the year of leveling out, and we think it’s going to be flat through 2018.” The company expects utilization to fall no more than 5% through the coming year, after which it should flatten out.

In terms of dayrates, some deepwater rigs are already working at rates in the high $100,000s – close to or under breakeven levels. And while there are still some rigs working under long-term contracts that are paying $400,000-plus, Quest expects some of these contracts to soon go through “blend and extend” negotiations that will result in lower rates but longer contract terms.

Further, early contract terminations are still running rampant. Pre-downturn, between 2009 and 2013, only nine floating rig contracts were canceled. But in 2014 alone, eight contracts were terminated early. That number increased in 2015 to 32. In fact, 60% were rigs that were stacked last year were ones whose contracts had been terminated early.

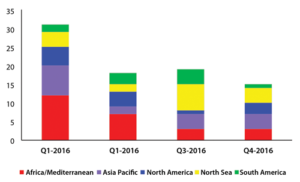

For 2016, 28 contracts have been terminated early as of the end of September – several were carrying high dayrates that were secured before the downturn. “The key drivers of these early terminations are high rates combined with low demand, a lack of sublet opportunities, and there just hasn’t been a shift toward using the rigs for other purposes like workovers and plug and abandonments,” Ms Cook said.

Geographically speaking, Brazil accounted for the biggest share of early contract terminations in 2015 – 35% – largely due to the bribery scandal. The US Gulf of Mexico (GOM) accounted for 30% of early terminations, and Africa accounted for 15%. In 2016, Golden Triangle regions accounted for 75% of early terminations, which have been evenly split across Brazil, the GOM and West Africa. Several major operators, including BP, Shell and Chevron, which have typically been active in the both the GOM and West Africa, appear to be prioritizing the GOM over other high-cost regions, Ms Cook said. She cited the higher costs of drilling offshore Africa as a major reason. “There’s about a 20% premium to work off Africa versus the Gulf because Africa’s not as mature and operators have to pay local content government fees.”

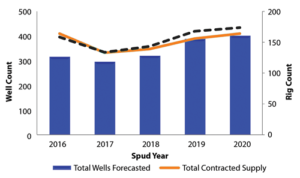

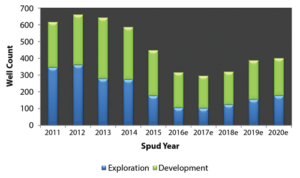

Regardless of geography, however, deepwater drilling activity overall is expected to remain flat into 2017. There will be little, if any, change from the total 316 deepwater wells that are expected to be drilled by year-end 2016. That breaks down to 105 exploration and appraisal and 211 development wells and represents a 30% decline over 2015 numbers. In that year, 448 deepwater wells were drilled – 177 exploration and appraisal wells and 271 development wells, according to Quest.

Operators pursuing cost reduction

Cost reduction and efficiency improvement have become top priorities during this downturn, but Statoil’s Stig Åtland points out that cost had become a big concern even when the price of oil was above $100/bbl. “It was apparent to us because we saw the costs were rising,” said Mr Åtland, Head of Offshore Exploration Drilling for the Norwegian operator. “The drop in the oil price has helped to show that now there is an apparent need to succeed on this in order to keep up activity.”

Back in 2013, Statoil had already launched a cost improvement agenda to reduce operational costs. The initiative has helped the company to increase by 70% its meters drilled per day on production wells. The total time required to drill wells has dropped by an average of 40%, and costs have decreased by an average of 30%, Mr Åtland said. Although lower rates for rigs and services have contributed to these achievements, he attributed much of Statoil’s cost reduction to simplifying and standardizing the planning and well design process.

The company has also reduced NPT by 10% across its exploration portfolio over the past year by ensuring that all service providers and rig contractors adhere closely to the required maintenance programs. “We make sure the maintenance program on the rig is according to what we expect,” Mr Åtland said. “We don’t have any overdue actions in our exploration rig portfolios; that’s not acceptable.”

Statoil also uses an approach called Contract the Best Supplier as a method of preventing NPT. Under this approach, the company includes terms in its service contracts that allow Statoil to change providers if there is too much NPT or if low-quality work is delivered.

Mr Åtland also suggested that operators increase their levels of collaboration amongst one another – especially those working in nearby deepwater locations – in order to drive costs down further. “We could, for example, share rig equipment or maybe also service providers between two operators instead of having two separate mobilizations and demobilizations for similar operations,” he said. Mobilizing a service company to a remote rig location can be quite expensive, he added. “If we can share the costs, that’s good.”

So far, Statoil has not attempted this type of collaboration because there hasn’t been an opportunity where another operator was working closely enough and was in a similar stage of operation. “It’s not a given that it’s the right solution, but if we are to reduce costs without bringing down the rig rates and service rates, then we need to look at project setups, and that brings us into more collaboration between companies.”

The company also sees value in using the same service provider to carry out as many services as possible on a given project, rather than relying on several different providers, particularly in remote frontier areas. “If a company has to establish themselves in a new country or new area that’s remote, it’s more efficient if one service company works on a project, rather than five providers,” Mr Åtland said. When Statoil was drilling offshore Newfoundland, Canada, last year, the company was able to utilize just one of the major service providers throughout the campaign.

In terms of technology, Mr Åtland pointed to managed pressure drilling (MPD) as something that’s highly enabling yet something that still requires more work to make it more modular. “The technology is fairly well known, but it’s still a big project to install it on the rig and get it up and running. We would like to see more plug-and-play systems.” Cost and time remain significant barriers to more widespread adoption of MPD technologies, he said, adding that having more rigs that are already MPD-capable could help.

Next year, Statoil is planning to utilize MPD to drill exploration wells in Brazil’s pre-salt beginning in Q3 or Q4. Offshore Canada, two additional exploration wells will be drilled beginning in May, though not with MPD. Statoil’s other major deepwater exploration project will be in the Barents Sea, which will be the operator’s largest project on the Norwegian Continental Shelf for the year. This campaign is expected to kick off in April. Worldwide, Statoil expects to drill between 80-90 wells in 2017, a decrease from the 120 anticipated for 2016 and 117 in 2015. Approximately 15-20 of the 80-90 will be exploration wells.

Streamlining processes

On the drilling contractors’ side, companies are bracing for another rough year in 2017 and continuing to explore ways of cost reduction. “I think every drilling contractor in the world has spent the last 24 months trying to work out how to reduce the cost of their operations and put themselves in the best shape possible, and Pacific’s certainly part of that,” Mr Beckett said. Over the past year, Pacific has reduced its overall costs by 30%, resulting in annual savings of $160 million. In addition, the company has lowered its rig operating costs by 25%.

Pacific Drilling’s smart stacking approach has brought stacking costs down to $30,000/day for a deepwater rig, compared with $80,000/day for a warm-stacked rig and $150,000/day for a hot-stacked rig. A smart-stacked rig can be ready to go to work in 90 days, according to Mr Beckett. “It’s very expensive to bring a rig out of a cold stack, and there’s a lot of uncertainty about the condition the rig is in when you try to do so,” he said. “What we did was try to find an approach that would get the costs down toward the same level as cold stacking but provide the benefits of warm stacking, or ideally, hot stacking. In other words, a rig whose condition we are sure of at all times.”

To enable this approach to stacking, Pacific looked at each individual cost source associated with stacking a rig. For instance, only the crews needed to do essential maintenance work are kept on the rig.

Another method of cost reduction has been encouraging operators to involve the drilling contractor earlier in the well planning process. For instance, an operator may want to use a particular type of drill pipe for a project that the contractor might not have onboard the rig. Switching out the pipe could add as much as $10 million to a project without adding any value, Mr Beckett said. “We’re working with clients to make sure they’re not over specifying the equipment sets they need, that they understand the cost benefits to the driller and, therefore, to them and to the whole system of using available equipment and not demanding new systems.”

At the same time, Mr Beckett said, there are opportunities for operators to more fully utilize contractors’ capabilities. For instance, in some projects the operator will have Pacific run casing strings or tubulars, while in other projects the operator may bring in a third party. “There can be a perception that a third party can bring a skill set that’s greater than what’s available on the rig, and I’m not sure that perception is always accurate,” he said. Certainly there are third-party operators with specialized equipment that can bring benefit to the process in some cases. However, when the specialized equipment requires additional people to deploy it, additional costs will be incurred. “We just have to look at the way we do some of these things and make sure we’re using the resources we have as efficiently as we can.”

Cost reductions are critical in the short term, but Pacific is also considering the long term. Whenever the market improves, contractors will have to ramp up multiple rigs simultaneously and bring in new people to work the rigs. The experienced workers will have to be distributed across the fleet to lead and train the new-hires.

In preparation for such an upturn, Pacific launched a leadership training program called Project Origin in January. “We’re focused on training our people to be better leaders and better managers so that when we spread them more thinly across our fleet, they’re capable of helping the new people to the industry learn quickly and do their jobs safely.” Every Pacific employee in a supervisory role will be trained through this program.

One rig is being trained at a time. Once crews return to the rig from classroom training, coaches will continue to work with employees one on one. This ensures what was learned in the classroom is being applied on the rig.

The leadership training program comes on the heels of Pacific’s late 2015 launch of a training center equipped with a cyber drilling simulator in Houston. The facility will be used to train new-hires when the market rebounds. “As we ramp up, we expect to bring people through that training program so they get the experience of what they’re going to be dealing with on the rig before they do it for real,” Mr Beckett said.

Uncharted territory

With the decline in exploration over the past two years, few E&P projects have received final investment decisions (FIDs) during this time period. Because it often takes two to five years from the time of FID to starting a drilling program, this means there will be very few large-scale, long-term projects for drilling contractors on the horizon, Lyndol Dew, Senior Vice President of Worldwide Operations for Diamond Offshore, said.

In turn, this means that marketed utilization for offshore rigs is unlikely to reach 85% anytime in the next year. “At 85% we start to see some pricing power,” Mr Dew said at the 2016 IADC Asset Integrity and Reliability Conference on 30 August in Houston. With the marketed utilization rate for deepwater rigs closer to 60%, according to Quest Offshore, operators are in a position to be as selective as they like about rigs. “They can choose the price, they can choose the rig, they can demand more things, and they can minimize the term they’re committed to,” Mr Dew said.

He also reminded the industry that operators favor high-spec rigs that are either rolling off contract or hot stacked. “If we’re going to work and we’re going to keep our crews together, we have to make the necessary decision to keep some rigs hot,” he said. “From the numbers that we’re looking at right now, all rigs can’t stay hot. It’s prohibitive to keep them hot. I think, as an industry, we will have to do more with less.”

Mr Dew believes that onshore unconventionals and shallow water will not be enough to fulfill global oil demand. He estimates that deepwater will need to produce 5.6 million bbl/day to fill the remaining gap. “Our industry is not dead,” he said. “Our challenges are many, but our industry is resilient. We always have come through and have always survived as an industry, and we’ve always done well when it turns around.” DC