Five years after Macondo

Significant progress has been made to improve offshore safety, but industry realizes that the journey is not over

By Alex Endress, Editorial Coordinator

Five years ago, a tragic blowout engulfed the Macondo well – devastating the Gulf of Mexico, the global drilling industry and, indeed, the people onboard the Deepwater Horizon. The magnitude of the blowout and resulting spill brought about a heightened awareness of how one incident, on one well, can have far-reaching consequences – nearly wiping out the industry’s social license to operate. It was an awful reminder of this industry’s responsibility to protect the lives of its people and the environment in which it functions.

Five years ago, a tragic blowout engulfed the Macondo well – devastating the Gulf of Mexico, the global drilling industry and, indeed, the people onboard the Deepwater Horizon. The magnitude of the blowout and resulting spill brought about a heightened awareness of how one incident, on one well, can have far-reaching consequences – nearly wiping out the industry’s social license to operate. It was an awful reminder of this industry’s responsibility to protect the lives of its people and the environment in which it functions.

Since that disaster, drilling contractors, operators, service companies, regulators and industry organizations like IADC have each embarked on a quest to make sure such events never happen again, in the Gulf and beyond. Among the first actions taken, just days after the blowout, was the formation of the Joint Industry Task Force (JITF). With more than 200 individuals representing 100-plus companies, the group immediately set out to draft stricter guidelines around drilling procedures and BOPs.

“The industry reacted very strongly. There was nothing that was too difficult or expensive to be done that would be ruled out in order to improve our resistance to major accidents,” Taf Powell, IADC Executive VP – Policy, Government & Regulatory Affairs, said. “Macondo was a game-changer because not only was it a very dreadful loss of life and total loss of the asset, but it was also a very significant pollution incident.”

The JITF ultimately developed a total of 78 industry guid elines and best practices related to topics such as well design, BOP reliability and containment. These were then submitted to US regulators, and many have been implemented into regulations since. The group also catalyzed the establishment of the Marine Well Containment Co (MWCC), which just completed and delivered its expanded containment system for the US deepwater Gulf of Mexico earlier this year.

elines and best practices related to topics such as well design, BOP reliability and containment. These were then submitted to US regulators, and many have been implemented into regulations since. The group also catalyzed the establishment of the Marine Well Containment Co (MWCC), which just completed and delivered its expanded containment system for the US deepwater Gulf of Mexico earlier this year.

In spill response, too, the industry has made significant advancements, Holly Hopkins, API Senior Policy Advisor, Upstream and Industry Operations, said. “The industry has done significant research in oil sensing and tracking using sonar and underwater drones. For shoreline protection, the industry has also made improvements in dispersant, sorbent and booming technology. If we were to have another incident, these improvements make for a more rapid, efficient and effective response. We are much better equipped overall.”

Still, while the industry recognizes the importance of bolstering critically important containment capabilities and response readiness in case of a blowout, most believe that prevention is king. Indeed, that is what the bulk of post-Macondo efforts have targeted. Driven by both regulatory actions and a heightened risk awareness, the industry has made sweeping changes in these five years pertaining to equipment and reliability; workforce training and competency assurance; and management systems and processes.

In this update on the state of offshore safety, DC speaks with industry representatives and regulators from the US and UK to highlight the progress made since April 2010, as well as the work that remains to be done. The journey is far from over.

Regulators react to Macondo

Aside from the drilling moratorium imposed in the blowout’s immediate aftermath, the most tangible regulatory change in the GOM after Macondo was the transition of the Minerals Management Service to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, which eventually led to the formation of the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). “There was a very positive movement in terms of the industry’s response (to Macondo), but I would add that there’s been an equal response from the regulators’ perspective,” BSEE Director Brian Salerno said. “BSEE came out of that event, and it really reflects a concerted effort to look at safety, whereas our predecessor organizations had a much broader portfolio. Those missions still exist, but our focus is on safety.”

By being an agency that focuses solely on safety, BSEE has been able to ingrain a shared understanding between the industry and regulators, Mr Salerno said. “That organizational transition has really changed the way we approach safety, and I think it had a very constructive effect on the nature of the relationship with the industry in terms of a concerted effort to improve safety.”

Randall Luthi, President of the National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA), agrees the formation of BSEE has resulted in “a cooperative, communicative relationship” between the drilling industry and regulators. “Right after Macondo, things got a little frosty because the regulators were under a huge public eye, so it was difficult to communicate shortly after the incident. Over time, that has improved drastically,” Mr Luthi said. “I think there has been a better meeting of the minds.”

One of the most significant pieces of offshore regulations that came out of the new agency is SEMS, which requires operators to implement safety and environmental management systems (SEMS) in order to remain active on the US Outer Continental Shelf. Requiring operators to cooperate with their drilling contractors and third-party service providers, the rule also incorporated existing API best practices for drilling, production, construction, well workover, well completion and well servicing. While many companies had been using such management systems in one form or another since the 1990s, the BSEE rule set out a clear and uniform expectation across the board.

In short, SEMS I and SEMS II were put in place to provide a baseline of safety performance, Mr Salerno said. “It’s essentially a performance-based approach to managing safety and managing risks, with a heavy emphasis on the human element,” he explained.

Within the first couple of years after Macondo and SEMS becoming a regulatory requirement, there was misunderstanding around SEMS audits and BSEE expectations regarding SEMS. The Center for Offshore Safety (COS) was established in 2011 to facilitate with compliance, to develop common practices around SEMS auditing and audit service providers, and to help the industry improve SEMS performance. “COS is unique in that we’re an industry association that only works on safety environmental management systems,” COS Executive Director Charlie Williams said. “We are continuously building better audit tools. We’re accrediting audit service providers, developing safety performance indicators and learning from incident data. Most importantly, we’re trying to build systems that can effectively measure SEMS effectiveness and determine what are the best areas of focus for work to continuously improve SEMS,” Mr Williams added.

Among key tools that the COS has put out is the SEMS Toolkit. It sets out practical guidance such as audit protocols, compliance readiness and operator-contractor audit tools, and knowledge and skills worksheets. COS has also provided a “leadership site visit” best practice.

Although the SEMS rules initially lengthened the process for attaining an offshore drilling permit, the industry is acclimating to the extra steps, Mr Luthi said. “We’re reaching that equilibrium where there’s a better understanding of what is required and, therefore, industry has a better knowledge of what to submit,” he said.

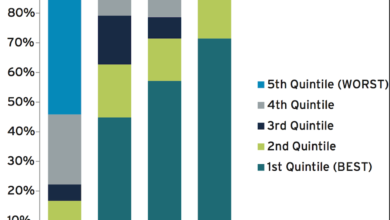

Looking at industry progress since Macondo, Mr Salerno praised parts of the industry but prodded other parts to do more. “Some companies clearly understand their role in managing safety and are pretty far ahead. (They) have been doing this without us telling them they had to – they were doing this on their own, and they’re the industry leaders,” he said. “The other end of the spectrum is companies that just want to know what’s necessary to be in compliance with the regulations, and it becomes a paperwork exercise. That completely misses the point of why we have SEMS.”

Although SEMS is a GOM-specific regulation resulting from a GOM blowout, Macondo’s impact did not stop with national boundaries. Many countries have reexamined their own regulatory frameworks and expectations. “Everywhere that there is a well-deployed regulator regime for safety and the environment, there has been a significant appraisal of whether their regimes are fit for purpose,” Mr Powell said. In particular, the International Regulators Forum, a regulator group comprising the US, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Norway, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand, evaluated SEMS policies both collectively and as individual authorities. “With all of this activity going on, it became quite clear that regulators were actually looking for different behavior from the industry.”

In Europe, the European Commission (EC) reacted to Macondo in a direct way by issuing proposals in 2011 for new legislation in the 28 member states of the European Union, including the UK, Denmark, Italy, Bulgaria and The Netherlands, as well as countries of the European Economic Area, including Norway. “A pan-Europe directive for controlling risks of major offshore accidents for safety, environment and economic liability came into force in July 2013,” Mr Powell said. He was appointed to be the EC’s expert adviser on offshore drilling and production during the drafting and negotiating of the legislation. “All the countries subject to the directive must implement the legislation into their national law by July 2015, and industry must comply within one year. IADC and organizations such as IOGP (International Association of Oil and Gas Producers) are monitoring the implementation plans with the aim of securing a new level playing field of offshore safety and environmental regulation throughout Europe. This will have obvious benefits for our industry.”

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has approached the issue by emphasizing the importance of controlling major accident risks by controlling hydrocarbon releases and ensuring the structural integrity of installations. The regulator also wants to make sure that senior industry leaders take responsibility for the control of major accident risks offshore.

“The drilling industry can only thrive by pulling off the right balance: producing/operating safely efficiently and reliably,” Susan Mackenzie, Director of Hazardous Installations for the HSE, said. “I understand the importance of drillers: Nothing is produced from a well without your rigs and people. You, therefore, are in control of what contribution you make to process safety and, as a consequence, the viability of the industry.”

Ms Mackenzie praised the IADC for the progress made in the past few years, noting that the North Sea Chapter, in particular, has been instrumental in preserving the industry’s ability to continue drilling operations on the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS). “The UKCS is not the easiest basin in the world in which to operate, and the IADC North Sea Chapter has clearly responded to my challenge to do something substantial towards process safety,” she said.

The chapter is currently developing guidelines for North Sea rigs around third-party contractor competence assurance. “IADC has worked hard to develop something that will ease the burden on rig management, whilst at the same time raising the bar on competence assurance of subcontractors attending rigs where the rig owner has no say in the contractual appointment,” Ms Mackenzie said.

Regardless of specific regulations that companies face in various jurisdictions, it’s clear that collaboration between industry and regulators will be paramount to further safety gains. “The regulators, the producers and the drilling contractors are the primary duty holders in safety and environment, which necessitates an open line of communication between the three,” Mr Powell said. “After regulators implement policy from an oversight perspective, producers must have the knowledge to implement new rules into well planning, and contractors must execute the plans.”

Fortifying equipment, securing the well

For obvious reasons, the BOP has been a core focus for most equipment-related work that grew out of Macondo. Within days after the incident, API began to update API Standard 53, “Blowout Prevention Equipment Systems for Drilling Wells,” which came to fruition in November 2012. It added procedures for the testing and routine maintenance of BOPs. Converting the RP into a Standard effectively mandated a number of equipment items and procedures that had previously been considered as “recommendations.”

A newer effort that is still under way is the BOP Reliability and Performance Information Database. IADC and the IOGP are collaborating on this joint industry project (JIP) – involving contractors, operators and service companies – to develop a BOP performance database to improve subsea BOP systems and related operating procedures. The JIP will be based on a platform established by the Subsea BOP Executive Group, more commonly known as the “Group of 7.” This consortium of offshore drilling contractors was motivated by the reporting requirements set by API Standard 53 to construct a system that will form the basis of the an ongoing performance database. “Equipment failures must be reported by the user to the manufacturer of the equipment, so the system was set up with that in mind,” Steve Kropla, IADC Vice President – Offshore Division, said. “When the JIP’s first phase launches later this year, it will track and report failures of BOP equipment and will eventually be useful for tracking BOP component reliability trends over time.”

Also related to the BOP, BSEE proposed a new regulation on 13 April on well design, operational procedures and integral well control equipment, including subsea BOPs. “The comprehensive rule will contain both prescriptive and performance based requirements that will reduce risks and save lives,” Allyson Anderson, BSEE Associate Director for Strategic Engagement, said. In particular, the regulation addresses BOP design, construction, maintenance and inspection. “We are proposing requirements for double shear rams and technology that increases the likelihood that a well can be safely shut in during an emergency,” Ms Anderson said. “We will also improve the information that’s collected on BOP component failures, which will help BSEE and industry identify trends in those failures and ultimately help prevent accidents.” The rule outlines third-party review verification that equipment will perform to design specifications, as well. “The proposed rule also has a new requirement for real-time monitoring. Having real-time data available for onshore personnel would increase the level of oversight throughout operation,” she said.

Per the proposed regulation, operators would be required to submit drilling plans describing formation pressure and well control options that would be used while drilling the well, including cementing, casing and subsea containment. “Despite the current downturn in oil and gas activity, long-term projections are for offshore activity to continue to grow. Therefore, it’s important that we get this right – that we reduce the risk to people and the environment to the lowest practical level, while allowing industry to perform its purpose of providing energy to the nation,” Mr Salerno said. “We believe this proposal sets the bar at the right level.”

BSEE will accept public comment on the proposed regulation until mid-June. Mr Salerno said he’s targeting early 2016 for implementation.

As most would agree, addressing the equipment itself is useless if the industry doesn’t also address the people operating and maintaining that equipment. Over the past five years, a multitude of companies have ramped up employee training and formalized competence assurance programs. Especially for drilling contractors, whose crews are at the heart of well control and BOP operations, people have been at the core of most post-Macondo initiatives.

Several major offshore contractors, including Maersk, Noble and Diamond Offshore, have committed significant capital investments to state-of-the-art simulator-based training centers. These facilities allow rig crews to apply knowledge gained in a classroom setting and hone various skills in a life-like environment. Some allow crews to train as a team, and some are able to re-create the exact environment of the drilling rig on which the crews work.

“We’re moving from an environment where we used to train people almost exclusively offshore for the tasks of their job,” Noble President, Chairman and CEO David Williams said in a 2013 DC article on the Noble NEXT Center. “Now, in order to be effective in our operations, we have to be far more structured, standardized and specific about the training that we provide. This center is built around that concept,” he said.

Industry organizations have also rolled out multiple competency-driven initiatives aimed at lifting the industry baseline as a whole. IADC has led such efforts in the drilling space, with the launch of the Knowledge, Skills and Abilities competencies database and the Workforce Attraction and Development Initiative. The association also recently launched WellSharp, which provides drilling, workover and subsea curriculums tailored to the post-Macondo world (see Page 20).

More specifically targeting well control is the establishment of the Well Control Institute (WCI), an independent subsidiary of IADC. “It’s in the early stages of establishing itself as the most influential and competent body for dealing with the priorities that are outstanding for improving well control,” Mr Powell said.

Industry buy-in to the WCI goal and vision is already evident, said Moe Plaisance, who agreed to chair the WCI after his retirement from Diamond Offshore last year. Management-level representatives who sit on the WCI board come from BP America, Cameron, Helmerich & Payne, KCA Deutag, Maersk Drilling, Murphy Oil and Gas, National Oilwell Varco, Noble Drilling Services, Petrobras, Precision Drilling, Saudi Aramco, Seadrill and Shell International. IADC President & CEO Stephen Colville will serve as a non-voting member, and IOGP Executive Director Michael Engell-Jensen has been invited to participate, as well.

“Our goal is to ensure that as we go into deeper water, or deeper and longer laterals on land, we’re capable of handling the changes that are required,” Mr Plaisance said. “As we push the boundaries and go further out, we must initiate action to address areas of well control in the drilling industry that need help.” In the late 1990s, Mr Plaisance served as Chairman of the task force that published the first IADC Deepwater Well Control Guidelines; he served as Executive Adviser to the recent rewrite of those guidelines, led by Louis Romo of BP. The new edition was issued earlier this year.

Looking ahead, the WCI will be working to address its top two priorities – competency, which encompasses scenario-based well control training and personnel credentialing; and safety management, which includes procedural discipline and communications. Other priorities that have been identified include BOP reliability, high-reliability systems, incident reporting and kick detection automation.

Procedural discipline is already an emerging area of focus for the industry. In September 2014 at the IADC Drilling HSE Europe Conference in Amsterdam, BP’s Director S&OR HSSE Richard Osmond put the issue front and center with his keynote address. Rules and procedures are present on every drilling rig, he said, but how does a company know if those rules and procedures are being rigorously followed?

After an analysis of incident data, BP launched an operational safety plan centered on improving procedural discipline. This includes engagement with front-line employees to ensure they have ownership of the procedures they will use. A self-verification process was also implemented to check that procedures are followed. “We’re working in collaboration with our contractors and service providers to strengthen procedural discipline and self-verification across our industry. We believe this will further drive improvements and reduction of incidents or gaps of procedure use,” Mr Osmond said at the conference.

Another still-emerging area of focus is using near-miss data to identify trends that could become leading indicators for safety incidents. Although many companies already capture near-miss information for internal use – and IADC introduced the Drilling Near Miss/Hit Report in 2013 – the bulk of near-miss data is not being put to rigorous use at an industry level.

To change this, BSEE is working with the Bureau of Transportation Statistics to launch a voluntary and confidential near-miss reporting system for the offshore drilling industry. “I know from dialogue with many companies that many of them are capturing information for their own use, but it’s not well shared,” Mr Salerno said.

In a presentation at the 2015 IADC HSE&T Conference in Houston on 4 February, Robert Middleton, BSEE Deputy Chief of the Office of Offshore Regulatory Programs, emphasized the confidential nature of the database. “This is not a regulator system. We can’t use it to regulate. We can’t use it to write incidents of non-compliance. It is purely one of information gathering and analysis,” he said.

The way forward

Significant progress has been made to improve offshore safety in the five years since Macondo – more than can possibly be captured in one article. But it’s clear that the path forward must be paved with a foundation of collaboration – between industry and regulators, between operators and drilling contractors, among different segments of the oil and gas industry. Only with collaboration will the industry be able to push ahead on process safety, just as it has done with personal safety over the past decades.

“I would say the great unfinished business of Macondo is to improve the reliability of our industry – to move toward a high-reliability platform, similar to the nuclear energy sector,” Mr Powell said. “The offshore exploration and production sector has taken very great strides in that direction through its collaborative programs, a very significant tightening of standards and recognizing that some things are not competitive.”

“Safety is not competitive, environmental protection is not competitive, and corroboratively poor performance in any one company in those areas of safety and environmental stewardship reflects badly on the entire industry,” Mr Powell continued. “In order to secure a kind of public acknowledgement of our fitness to operate, we need to demonstrate our stewardship as an industry of our core values for safety and the environment.”