Automated systems steer wells to better paths, and with optimized execution

AI and digital technologies advancing industry’s ability to precisely place wellbore in best geology while still reducing days vs depth

By Stephen Whitfield, Senior Editor

For a long time, drilling as fast as possible was one of the driving metrics for measuring performance. If a drilling contractor and an operator could drill a well an hour or even a few minutes ahead of schedule, that well was considered successful. However, as the geologies in which the industry drills its wells becomes more complex, multizone developments and pad-drilling applications become more commonplace, and production timelines tighten in a more capital-constrained economic environment, the accuracy of the wellbore’s placement is becoming an equally important measure of success.

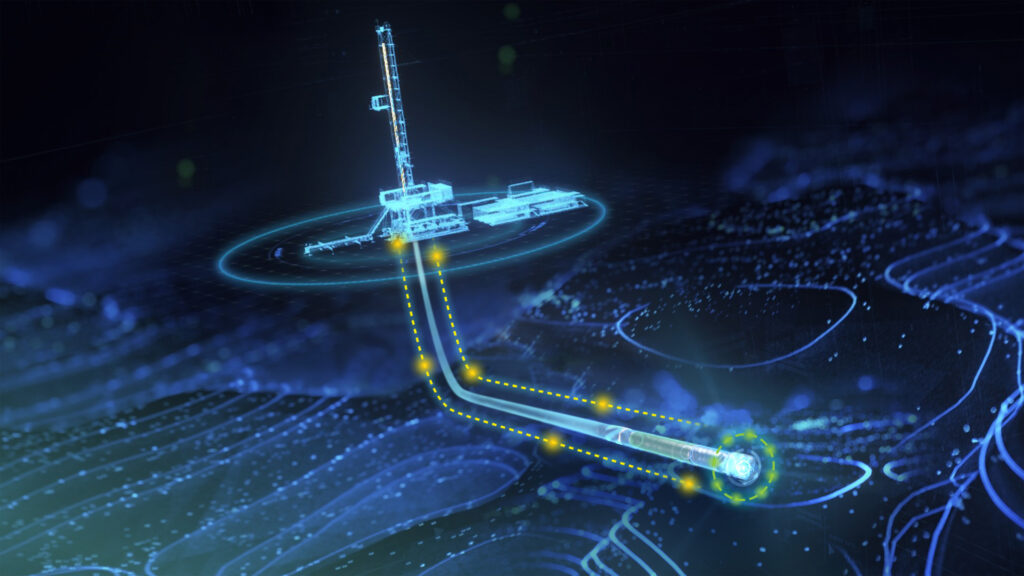

Digitalization and automation tools have helped the industry drive efficiencies in drilling operations and other areas of asset development and management. Specifically in the area of well positioning accuracy, digital resources are helping companies reduce the ellipses of uncertainty around wellbore trajectory in directional wells, mitigating the risk of wellbore collision and enabling drillers and operators to avoid costly errors downhole.

“When we talk about optimizing the wellbore, we’re talking about the convergence of a few elements: the accuracy around trajectory in real time, the execution, and the understanding of reservoir characterization,” said Chuks Akpenyi, Digital Subsurface Champion at SLB’s Well Construction Division.

“When the technologies that enable these elements are integrated, we have the best of both worlds,” he continued. “Ultimately, that’s what we’re driving. It’s really important to understand that there’s a convergence of technologies in different disciplines, like drilling, reservoir evaluation, geology and geophysics. We’re bringing all of them together to make sure that customers have the best shot at maximizing asset performance.”

However, even as the industry works to reduce the uncertainty in wellbore placement, the need to deliver wells quickly has not gone away. Operators are still looking to reduce drilling time and, in the process, lower their costs. Automation and digitalization can help deliver both – even if the systems used to optimize accuracy sometimes come at the expense of rate of penetration (ROP), they can still help operators minimize the amount of time spent in hole by reducing nonproductive time (NPT) and the total days spent in hole. These efficiencies can generate significant savings per well.

“At the end of the day, we know that what’s most important to our customers is time. Time is money,” said Todd Fox, Director of Product Management at H&P. “Reducing days vs depth, reducing hours in the curve, and being able to get casing to bottom. So, our customers are very in tune with not chasing instantaneous ROP. They’re chasing the lowest days versus depth for the well. A lot of our contracts have performance elements in them, so we’re in lock step with our customer base at using technologies that can help minimize days vs depth.”

Drillers and service providers alike agree that the human will continue to provide valuable insight into optimizing the wellbore. Automated systems can perform the repetitive calculations and measurements that can often lead to human error, but humans still have the historical knowledge of what a BHA might do in a given geology, or when faced with a given anomaly. Incorporating that knowledge into the increasingly automated downhole environment will help to deliver even more accurate wellbores.

“Every system is different, but you need rules if you’re trying to automate anything, and if your rules don’t make sense, then the system doesn’t know what to do,” said Alex Genthon, Directional Coordinator at MS Directional. “Automation cannot say that something’s coming up in 500 ft. It’s not to the point where it can be intuitive. It’s garbage in, garbage out. There are certain things that a directional driller just knows might happen – even if the numbers don’t make sense – and they know to take a certain course of action.”

Using automation to merge disciplines

Mr Akpenyi described the current challenge of optimizing wellbore placement as enabling “the convergence of the accuracy around trajectory, execution and understanding reservoir characterization in real time.” Over the last few years, SLB has focused on maximizing digital and automation capabilities to help the industry better understand the geology of a given field and minimize the need for human intervention in positioning the wellbore, saving time and cost for the operator.

At the heart of these efforts is the company’s Neuro autonomous solutions portfolio, launched in 2022. The first system in the portfolio, autonomous directional drilling, uses AI algorithms built within surface and downhole automation workflows to self-determine steering sequences.

Neuro autonomous solutions for drilling consist of four separate subsystems: a subsurface adviser that interprets subsurface data to create a comprehensive visualization of the reservoir; a directional drilling adviser that uses the interpretations from the subsurface adviser to recommend an optimal trajectory for the wellbore; an intelligent downhole system; and a surface advisory system. These four subsystems combine and automate directional control as the well is drilled.

“What we’re doing with this is to better understand the structure of the geology,” Mr Akpenyi said. “We’re leveraging machine learning to handle model training, which means that, as we run the physics to identify the different layers of the geology, our global models and the local models we utilize for a specific well will help us derive the best levels of accuracy and precision in interpretation. It’s a system that gives us the highest level of confidence in reservoir mapping and interpretation, which helps us with the accuracy of the wellbore.”

The intelligent downhole and surface advisory systems are particularly useful when using a rotary steerable system (RSS). Drilling with an RSS traditionally requires manual operation, involving a command sequence applied repeatedly to control the curve trajectory. This sequence is often comprised of multiple interventions and downlinks from the directional driller at surface for steering force, toolface orientation and measurements. The tool data is then fed back to the surface for adjustments in commands.

Mr Akpenyi said that this process, also known as control-loop time, can take several minutes to complete. By automating the downlinks within Neuro autonomous directional drilling, the process can become instantaneous.

“Downlinking is really just messaging,” he said. “When you automate it, that messaging triggers itself when needed, and the system knows when to change commands in the direction of the well to what extent is needed and for however long it is needed. The downlinking connects the onboard computers with the tool downhole, giving us another dimension of accuracy in placing the trajectory.”

Another benefit of the automated downlinking capability is that it reduces the amount of downlinks needed during drilling. For instance, an operator in the Middle East used the Neuro system in 2022 to autonomously drill a well from 22° to 90° inclination with a 2,500-ft curve section and a 5,400-ft lateral section.

The Neuro system minimized the number of downlink commands needed to meet all primary targets. For the well, the operator drilled a 61/8-in. lateral section from a measured depth of 9,417 to the total depth of 14,828 ft, averaging one downlink sent every 258 ft. The length between downlinks marked a 36% improvement in the average length between downlinks compared with offset wells that did not use the technology. Additionally, the Neuro system reduced the time spent for off-bottom downlinks by more than 80%, bringing the aggregate time to only 10 minutes for the entire well.

Last year, SLB added autonomous geosteering to the Neuro portfolio, a closed-loop system that integrates and interprets subsurface information in real time to autonomously guide the drill bit through the “sweet spot,” or the most productive layer of the reservoir.

During conventional geosteering operations, geologists manually interpret subsurface data to identify a well target, update the well plan and trajectory, and communicate this plan to the directional driller. The Neuro system does all of this by itself, effectively removing the need for human intervention in geosteering and reducing the time needed to complete a geosteering trajectory change.

Last year in Ecuador, SLB deployed Neuro autonomous geosteering to drill a 2,392-ft lateral section in an onshore well for Shaya Ecuador. During this operation, the Neuro system completed 25 autonomous geosteering trajectory changes, with each interpretation and decision cycle taking an average of 22 seconds.

Guiding the bit

While automation also holds priority within H&P’s efforts to optimize wellbore placement, the company recognizes that the human perspective cannot be ignored. Mr Fox noted that automated systems are still unable to fully replace the driller’s intuition and insight.

“At the end of the day, there’s no substitute for a knowledgeable human to acknowledge that certain points are so critical and so costly if we’re wrong,” Mr Fox said. “At different points in the well, different pieces of technology require very light touches from the human, versus a more deliberate use at some points. We still don’t have a looking glass into all of the geology downhole, and that’s an uncertainty that’s still difficult to overcome.”

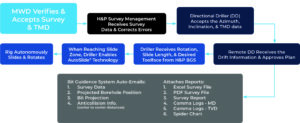

The company’s Bit Guidance System (BGS) aims to strike that balance between human and machine insight with the wellbore. BGS is a cognitive computing system that makes steering calls for conventional, bent motor directional assemblies.

“Bit Guidance is a combination of edge and remote cloud computing to make optimal decisions. It’s running all the math and looking at every different wellbore trajectory to say, actually, this one wellbore trajectory makes the most sense all the way around. Once you get to a certain depth, it directs you to execute a slide, hold this particular tool face for this many feet,” Mr Fox said.

The system takes directional surveys captured by a measurement-while-drilling (MWD) provider into an electronic data recorder (EDR) and creates a feed that can be communicated to the rig using one of two ways. One is through the deployment of a computer and communications gear to the wellsite, which is then tied into the required WITS0 feeds and display outputs over a Wi-Fi network set up to H&P’s tablets. The other option is data via WITSML from the EDR provider outbound to an H&P remote command center, where the information is fed into a dedicated hub.

After the data is communicated to the rig, it is analyzed before the output calculations are sent back to the EDR through a browser tab and displayed on a dashboard with the go-forward steering or rotate calls. AI and machine learning algorithms within the BGS then calculate the well path that would reach the target in the shortest amount of time.

The BGS can be used in conjunction with H&P’s AutoSlide software to automate control of surface equipment and steerable mud motors. However, even with that automation, Mr Fox said the BGS is meant to serve as a complement to the operator and the directional provider, rather than replace them outright in the process.

For one, operators have the option to not use the AutoSlide software with BGS, making the system more of an adviser for personnel who are manually handling the BHA. The system still requires well plans, surveys and offset well data – the same information that a directional provider and operator would exchange to execute a well not using this system.

However, even if an operator chooses to use AutoSlide, H&P personnel and the operator will still select various parameters that will be entered into the BGS, such as the distances or drilling windows that the operator wants to maintain, the dogleg severity maximums, survey frequency, highs and lows above target or slide, and any “no slide zones” based on geological conditions. H&P can then input multiple targets into the BGS and make changes to accommodate changing drilling conditions that AutoSlide can execute in real time.

Mr Fox said this flexibility, bringing humans into the automation process, is valuable for accounting for unexpected anomalies that come up during drilling. “When you look at something like an unexpected fault, the offset well data might not show it. The geologists might not realize it’s there, but you find an unexpected fault that may require the well plan to be adjusted. There may be unexpected water flow from that fault that could cause some issues. Knowing that you have knowledgeable eyes watching the data and bringing you in when needed, working together on a solution to either adjust the well plan or drill ahead, is extremely valuable.”

The BGS has proven useful in helping operators save time and money reaching their targets, both with and without AutoSlide. One operator in the Eagle Ford Shale used BGS on a pad in which eight wells were drilled within 1 mile of one another at approximately the same time, with nearly identical lithologies, well path geometries and BHAs.

Not every well on the pad used BGS. The system was reserved for four wells with complex well geologies and longer laterals – the non-BGS wells had an average of 5,300 lateral ft versus 6,600 lateral ft for the BGS wells.

The wells that used the BGS saw significantly better results in drilling time, accuracy and tortuosity compared with the non-BGS wells. The BGS wells stayed within 5 ft of the well plan 79% of the time, compared with 44% for the non-BGS wells. Further, the BGS wells saw zero percent NPT due to MWD or mud motor failures, compared with 13% MWD mud motor-related NPT on the non-BGS wells. This led to an overall per-well savings of 28 hours of drilling time on the BGS wells, which H&P calculated was equivalent to approximately $70,000 in cost savings per well.

A major operator also used BGS in conjunction with AutoSlide software and another H&P system, the DrillScan software, to help mitigate the risk of unplanned trips in drilling a challenging well in the Haynesville Shale. In particular, the operator was concerned about the high torque and drag it found after drilling the first two wells on the pad using manual slides.

The DrillScan software showed high friction factors caused by high wellbore tortuosity in the first two wells. This information allowed H&P personnel to recommend that the operator lower the doglegs in the curve from 10°/100 ft to 8°/100 ft. While drilling, BGS collected data to make more efficient sliding decisions that were autonomously executed using AutoSlide. Wells 3 and 4, drilled using the BGS/AutoSlide/DrillScan software combo, reduced the average on-bottom drilling hours from 196 to 139 compared with Wells 1 and 2. This 57-hour saving equated to a reduction of approximately $140,000/well, according to H&P.

While BGS was originally developed for bent motor drilling applications and not configured for RSS tools, Mr Fox said the company has begun field testing on a remote RSS downlink.

“This new functionality will essentially mitigate potential mistakes by the driller,” he said. “It enables those RSS suppliers to send downlinks with extreme confidence, knowing that there is no human in the loop. When they submit their coded message to their tool, it’s executed flawlessly and they get acknowledgement back wherever they are in the world.”

Making the best use of digital tools

Through one of its companies, Superior QC (SQC), Patterson-UTI utilizes a cloud-based FDIR (fault detection, isolation and recovery) system within its Automated Directional Drilling Control application. The system uses machine learning algorithms to provide real-time corrections, maximizing exposure to targeted production zones.

SQC also offers the HiFi Nav survey management system, which estimates rotational tendencies and motor yields, and the HiFi Guidance bit guidance system, which feeds those estimates into machine learning algorithms to calculate the optimal shape and trajectory of the wellbore. HiFi Nav continually adjusts its estimates in real time and feeds them to HiFi Guidance, allowing for optimized forward projection and scheduling through a given well section. For the directional drillers who use these systems, there is great benefit to having increased automation in executing the well plan and bringing the BHA to target.

These types of systems that provide alerts to potential collision risk, whether from SQC or other data aggregator software providers, can be especially valuable on large pad drilling sites, said Mr Genthon of MS Directional, another subsidiary of Patterson-UTI.

“With bigger operators that have a bunch of rigs on a pad, and you have situations where two rigs are drilling right next to each other, we want that software to alert people in real time and tell us that we’re drilling tangents toward each other. How far away are they? Do we need to be concerned?” Mr Genthon said.

He pointed to HiFi Guidance, which uses standard MWD survey data along with the real-time rotational tendencies and motor yield estimations from HiFi Nav to calculate wellbore shape and trajectory in 15-ft increments. “Some companies will batch-correct after a certain section, and some might do it after every survey, rather than after 10,000 ft of survey. That can affect you because positioning could change greatly – typically 25 to 150 ft – over that course length. With SQC, you just send them the surveys and they send you back the corrected surveys right away, whatever that looks like. There’s not really a huge time consumption from our standpoint. We give it to them, and they spit it right back out,” Mr Genthon said.

However, even though these automation systems are key drivers in delivering more accurate wellbores, they are not perfect, he said. For example, there is the lack of intuitive user interfaces (UIs), the screens by which the driller views all of the data being processed by the systems.

“The interfaces are just data aggregators,” Mr Genthon said. “You have a time breakdown, you have the BHAs, you have performance reports, and you can build off of all that data. It is just putting everything in one place. That cuts steps out of the process, and it can potentially save you in situations where someone doesn’t see an issue and they accept a target change without having that information. But nothing’s really AI, per se, from the directional drilling standpoint. You’re putting in parameters of what you think is going to happen and you’re getting results based on that.”

Mr Genthon said he would like to see UIs for automated systems incorporate more historical data in real time during drilling. This centers around the basic function of automation systems as the ultimate data processors. While these systems can interpret data and advise the directional driller on the optimal trajectory, providing historical context in real time would put less pressure on directional drillers to rely entirely on their own past experiences in recognizing anomalies or situations where the wellbore trajectory may need to change from the plan generated by the system.

“I would like to see something that’s more like a pop up – say, at this depth and with this BHA we did this, or we saw this ROP. You can go find that information if you know what you’re looking for, but it takes time. With AI, I think that information could come automatically. There are some systems that use historical data to give you a guide of drilling parameters and expected ROP, but more often than not, those are data files loaded by the software provider, with only known offset data sets. It will typically not include every well drilled in a given area.” DC