Alliance model helps Aker BP and its partners adapt to market volatility, stay competitive

New way of working allows for long-term planning, sharing of value gained, and an integrated approach promoting collaboration

By Jessica Whiteside, Contributor

Seven years after Aker BP announced it was forming two separate tripartite drilling and well alliances with selected contractors in the Norwegian Continental Shelf, have these alliances delivered on their mandate to increase the efficiency of drilling operations? For the most part, yes, according to alliance partners who spoke at the 2024 IADC HSE & Sustainability Europe Conference in Rotterdam in September.

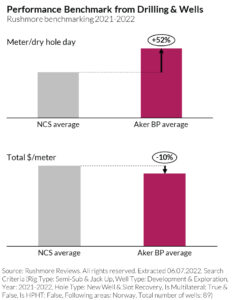

“Our model is working really, really well in terms of efficiency. We are dominating the area,” said Eamon Condon, Vice President, Drilling and Wells – Alliance Support Team for Aker BP. He cited Rushmore Reviews benchmarking data showing that Aker BP’s meter/dry hole day average is significantly higher than the operator average for the Norwegian Continental Shelf while its total cost per meter comes in below the average.

Mr Condon attributed the efficiency gains to the long-term engagement of the alliance partners and their embrace of digital technologies, including digital well planning and field development planning software, as well as collaborative well planning between subsea and drilling and wells disciplines.

“For us, the end game is actually getting oil onto the market earlier, and we believe this model is really helpful in doing that safely and effectively.”

Under the alliance model, the Aker BP-operated Kobra East & Gekko development in the Alvheim area of the North Sea came onstream under budget and about four months earlier than projected. The project was highly complex, involving four multi-branch wells and subsea installations connecting to an existing production vessel. Mr Condon called the project a great example of what an alliance can do “by bringing together one team towards a common goal and shared incentives.”

Alliance structure

For Aker BP, the alliances are part of a strategy to drive the innovation needed to stay competitive and adapt to future volatility amid the uncertainty of geopolitical and energy security concerns, the energy transition and the digital and AI transformation.

“With the world in constant change, we need to work differently, we need to work more collaboratively, and we need to work better together,” Mr Condon said.

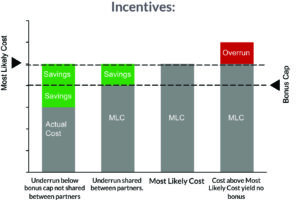

The alliances are structured around three key elements designed to create more value for all partners: a long-term contract that provides continuity through project phases, an incentive scheme that shares the rewards of efficient performance, and an integrated “one team” approach to the pursuit of shared productivity, quality and HSE goals.

In an alliance, the operator and its suppliers relate to each other as more equal partners than allowed by the traditional operator-supplier (order giver/order taker) dynamic. They work collaboratively to plan activities, and there is greater transparency in the exchange of information between partners and greater input from suppliers into early-stage planning and project decision making, although the operator remains ultimately accountable.

“It’s a much more empowering environment where you really want your suppliers and your partners to come on board, be part of one team and give all the best they have,” Mr Condon said.

Aker BP has formed a total of seven alliances: two for platform construction, one for subsea infrastructure and pipelines, one for operations and integrity management, one for well interventions and two for drilling and well construction.

The two drilling and wells alliances include a jackup alliance – with Noble Corp and Halliburton – and a semisubmersible alliance – with Odfjell Drilling and Halliburton. These alliances first formed in November 2017 for a five-year period, during which over 450 km were drilled and more than 100 wells were delivered. In January 2023, the partners renewed the alliances for another five years, extending their commitments to 2028.

The rig alliances’ level of activity will be significant over the next few years as the partners contribute to the development of approximately $20 billion worth of Aker BP projects, including drilling more than 50 wells for the Yggdrasil development.

Long contracts: benefiting from continuity

Because the alliances allow services and rig capacity to be planned out over such a long period, the partners have the security to invest in upgrades and new technologies, including advancements in automation, said Arne Kvamsdal, Vice President Global Account for Halliburton.

“The long-term part of the alliance gives us the opportunity to actually invest in new solutions that will bring the industry forward,” he said. The alliance is open to evaluating solutions from companies other than the partners that could benefit the alliance, but the decision will come from the alliance, not the operator.

The longevity of the alliances also empowers the partners to work together on strategies to address future challenges, which in the Norwegian Continental Shelf includes trying to extract value from smaller pools of oil once the big and easy finds are gone. The alliances are already setting up teams and thinking about different technologies and business models to address such challenges and generate activity for one another beyond 2028, Mr Condon said.

“We get to think about it now, and we get to work on solutions.”

Incentives: sharing success

From an operator point of view, it’s important to have a healthy supply base, Mr Condon said. For that reason, the alliances’ incentive scheme is based on the concept that when you succeed, you share a part of the winnings. If a well comes in under its projected cost, for example, the savings are shared appropriately among the partners.

“We wanted to create a win-win where when we as operators were getting onto the market earlier, we were sharing financial elements with our investor partners,” Mr Condon said.

Flexibility and negotiation have been key to getting the incentive model to a place that is amenable to all partners. The initial model didn’t cut it because “as we moved along and our performance was good, there was a risk of margin deterioration, but there is a mechanism to discuss that at the steering committee, so we have adjusted the performance versus the incentive over time – and yeah, we are happy,” Mr Kvamsdal said.

The financial model has proven to be an effective motivator.

“If there’s no earnings, then we wouldn’t be here,” said Stein Harald Nielsen, Vice President Operations for Odfjell Drilling.

Collaboration: reinforcing the alliance mindset

The alliance model is based on a “one for all, all for one” principle that aims to create an environment where the partners want to help each other succeed and are open to new ways of co-creating solutions.

To aid collaboration, there’s an alliance management team with representatives from all partners. In addition, certain teams from each partner are co-located, either on the rigs offshore or in an onshore operations center, which helps to boost understanding of each other’s systems, risks and schedules. While a “one team” mindset has always been more prevalent on the rigs, the alliance approach has enabled the partners to establish much greater cooperation among their onshore organizations, enabling the partners to “know each other on a different level,” Mr Nielsen said.

The partners have added some extra roles to their organizations to support effective integration with the alliance, though how those resources are configured differs by company. Some sharing of expertise among partners has also taken place in the form of personnel secondments.

The partners share some HSSE resources and are very aligned on their HSSE strategies and safety initiatives, which has contributed to a downward trend in high-potential incidents, serious injury frequency and other safety metrics. Tor Kvinnesland, Alliance Manager for Noble, emphasized the importance of spending time on making good bridging documents to align procedures before starting a project.

“We are one team, and we have one goal – but we have potentially different procedures on how to get there that we need to be aware of,” he said.

The alliances engage in frequent and transparent communication. This includes biweekly after-action reviews, which are three-way feedback sessions among the partners about lessons learned from incidents, as well as from positive findings. The experience is different from the traditional performance scorecard rig contractors are used to getting from an operator, Mr Kvinnesland said.

“It’s very much a three-way dialogue instead of a one-way dictation.”

An alliance mindset manual explains to crew members what’s expected from them while working in an alliance environment. There’s also a weekly alliance newsletter with updates on what’s been happening on the rigs.

“There’s an awful lot of extra branding, effort and energy to keep that mindset of ‘We’re in an alliance, this is different,’” Mr Condon said.

The effect of all this communication is that the partners are able to catch learnings from each other more quickly than in a non-alliance environment, benefiting safety performance.

“Our ambition is that if anything happens on a rig any day, then by the next day, the other rigs understand what’s happening, too,” said Mr Condon. “This is a key element of working safer in the alliance system.”

Can the Norwegian alliance model work elsewhere?

The drilling and well alliances have had 20 or more different operators come to learn about how they work. However, Mr Condon stressed that the alliance model used by Aker BP and its partners may not be for everybody as different companies and jurisdictions have different challenges to be considered. He advised that for an alliance of this sort to work, there must be trust among the partners. When the drilling contractor shifts from an order taker to a trusted adviser under the alliance model, that trust has to build over time and doesn’t come in the first year, Mr Nielsen cautioned.

“We had to kind of get to know each other,” he said of the early days of the semisubmersible alliance.

Mr Kvamsdal said he thinks companies could take some elements of the Norwegian alliance model and use them anywhere. However, for an alliance to succeed, company cultures and missions must align, which could be more challenging to achieve for an international alliance spanning more than a single country.

Another factor in the success of an alliance is executive support and strong governance from the top of the organization, Mr Condon said.

“Unless you have the CEOs and COOs of companies believing in this model, it’s not likely to work.” DC