Deepwater drilling segment reaches nadir in 2017, may see beginnings of a steady recovery in 2018

Activity is expected to pick up next year as operators achieve impressive cost reductions, but dayrates will remain low until rig oversupply is worked out

By Kelli Ainsworth, Associate Editor

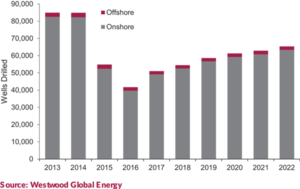

As the deepwater drilling industry looks toward 2018 and beyond, here’s the silver lining: The worst is likely over. Conditions are still difficult, with few work opportunities available for the large supply of deepwater rigs worldwide. However, companies can take some comfort in the fact that things appear to be on the mend, if slowly. “We believe 2017 does actually represent the nadir of activity in deepwater wells drilled,” said Ben Wilby, an analyst with Westwood Global Energy Group. “It increases next year and then increases steadily for the foreseeable future.” This means rig utilization will also see a slow and steady increase beginning in 2018, although a still-oversupplied rig market is expected to keep dayrates down for the foreseeable future.

In 2018, deepwater development drilling is expected to rise, although it won’t reach 2014 or 2015 levels, when more than 220 wells were drilled each year. Westwood Global Energy forecasts that the number of deepwater development wells drilled next year will rise to around 170, from close to 150 this year. Exploration drilling, however, is forecast to stay flat, with the number of wells drilled holding steady at approximately 45.

On the cost side, results continue to be impressive. Even before the downturn – when oil prices topped $100/bbl – high costs had already become a significant concern for operators with deepwater exploration and production projects. Back in 2013, for example, BP took its Mad Dog Phase 2 project in the US Gulf of Mexico back to the drawing board. The initial design, with a price tag of $20 billion, was already considered too costly and too complex. The operator and its partners then simplified and standardized the platform design and in December 2016 sanctioned a much leaner $9 billion project after trimming costs by approximately 60%.

Cost reductions, such as what BP achieved with Mad Dog, will be critical for operators to make more deepwater projects viable going forward. The good news is, most operators appear to be achieving great success. Breakevens for some deepwater projects have already fallen below $40/bbl from a typical range of $70 to $80/bbl just a few years ago, according to Mr Wilby. “Some pre-downturn breakevens were even over $100/bbl, and it was hard to understand how they even got sanctioned at all when a small drop in the oil price would have made them uncommercial,” he added.

Simplification and reengineering of projects, combined with lower rates for rigs and services, have been primary contributors for the cost reductions achieved. The majority of projects now break even at $30 to $40/bbl. Some deepwater projects can even break even below $30/bbl. In August 2016, Statoil announced that the breakeven price for Phase 1 of its Johan Sverdrup development in the North Sea had been brought down to $25/bbl. Initial breakeven estimates for the field were more than $50/bbl, Mr Wilby said. “What we’ve seen is that operators are spending a lot of time evaluating a project before they push forward in a way they maybe weren’t in 2012 or 2013,” he added. “Hopefully it’s something they keep up when the oil price improves.”

Although portions of the cost reductions will likely be lost when the market improves – rig and service rates will inevitably rise again – other parts could be sustained. In BP’s Q2 earnings call in August, Group Chief Executive Bob Dudley noted that he expects the company’s overall unit production costs to be 40% lower for 2017 than in 2013. “Around 75% of these cost reductions are from efficiency, so these should be sustainable over the long term,” he said.

Some operators are achieving sub-$50 breakevens for select deepwater projects even with higher rig dayrates that were signed before the downturn began. Transocean CEO Jeremy Thigpen pointed out in the contractor’s most recent earnings call in August: “It’s important to note that many of our customers are achieving these lower breakevens with rigs that were contracted in the last upcycle, when dayrates were two to three times higher than current market rates.”

Deepwater contractors also recognize that they continue to face stiff competition from the North American shale market. Shale projects require lower levels of investment and cycles around relatively quickly from investment to returns. But deepwater contractors also know that shale resources alone will not satisfy the world’s energy demands. In the long term, deepwater resources, which typically come with much larger production volumes, will still play a critical role in the global energy landscape.

Further, shale operators will eventually have to start drilling outside their sweet spots in the shale plays, said Michael Acuff, Senior Vice President, Commercial, for Pacific Drilling. This will push project breakevens up, “which will help make deepwater more competitive.”

Utilizing existing infrastructure

Several major projects that were sanctioned before the downturn are projected to come onstream in 2018. These include the Kaombo field offshore Angola and the Egina field offshore Nigeria, both operated by Total. In the Gulf of Mexico, Chevron’s Bigfoot, in the Walker Ridge area, will also come onstream in 2018. These projects, among others, will help to push up deepwater production by an estimated 7% next year, according to Mr Wilby.

“If you look at production, it looks great for deepwater, but that does hide the more complex picture of projects not really getting sanctioned, or those that are getting sanctioned being a lot smaller,” he said. “Construction-wise, a lot of projects going forward today are subsea tiebacks rather than these huge, five-year build-cycle FPSO projects.”

One example of this is the Buckskin project in the Gulf of Mexico’s Keathley Canyon area. The operator, LLOG, has contracted Seadrill’s West Neptune drillship to begin drilling two development wells starting in Q4 2017. Initially, the field was going to be jointly developed with the Moccasin filed, and both fields would use a floating production semisubmersible. Now, the wells will be tied back to the Lucius platform, operated by Anadarko.

The preference for tying new wells back to existing platforms is influencing exploration activity. Particularly for exploration wells in frontier areas, infrastructure-led drilling has dominated, with operators preferring prospects with lower-cost tieback potential, Andrew Hughes, Head of Research, Global Exploration for Westwood Global Energy Group, said.

While this approach allows operators to develop new projects at a lower cost, operators cannot stick with this approach indefinitely. Eventually, they will have to engage in more frontier exploration, Mr Hughes said. “The lack of FIDs today is, by definition, going to limit the number of infrastructure-led opportunities in the future,” he said.

In terms of exploration, Brazil is poised to be one of very few bright spots in 2018, with seven high-impact wells being planned, Mr Hughes said. Five of these wells will be drilled in the frontier areas of the Barreirinhas, Ceara and Foz de Amazonas basins along Brazil’s Equatorial Margin, as well as the Camamu-Almada basin.

“However, the Foz de Amazonas wells may not be drilled if the operator fails to gain the Brazilian environmental regulator’s approval for their environmental impact studies,” he said. The two remaining wells will target the more established Espirito Santo Basin. All of the wells that are expected to be drilled in deepwater Brazil in the coming years are commitment wells that operators must drill to hold on to their acreage, Mr Hughes noted. Other areas of the world where deepwater exploration is expected to continue in 2018 are the US Gulf of Mexico (seven wells), Cyprus and Australia (four wells each).

Although exploration drilling in the first half of 2017 was 20% lower than H1 2016, the commercial success rate for exploration wells went up from 30% to 53% in that time period. “Westwood suspects that O&G companies were drilling out the last of the commitment wells held in their exploration portfolios in 2016,” Mr Hughes said. “This resulted in wells being drilled that were high or very high risk in terms of commercial success. In Westwood’s view, 2016 was the worst year on record for discovered commercial hydrocarbons.” For 2017, notable deepwater finds include the Payara and Snoek wells in the Suriname-Guyana Basin by ExxonMobil.

Rig oversupply persists

Along with increased production, the deepwater market is expected to see a small uptick in rig utilization in 2018. Current marketed utilization for floating rigs sits at 74.1% globally, compared with 71.4% at the same time last year, said Cinnamon Edralin, Senior Rig Analyst for IHS Markit Petrodata.

Of regions with more than 10 floating rigs, utilization is highest in South America – primarily Brazil – at 88.7%. This is due in large part to long-term contracts that were signed before the downturn, Ms Edralin said. “Petrobras has terminated some contracts early, but most of their contracts are still progressing, and many of these rigs are under five or 10-year charters, so they weren’t really impacted as much as some of the other regions.” Further, Brazilian law does not allow foreign rigs to be stacked there, which helps prop up the region’s utilization rate.

Many idle rigs that can’t be stacked in South America end up being stacked in West Africa. This practice, along with low activity offshore West Africa, has pushed that region’s marketed utilization rate down to 56.1%, Ms Edralin said.

The US Gulf of Mexico and Northwest Europe are faring better, with marketed utilization rates of 74.9% and 82.7%, respectively. In fact, Ms Edralin noted that the floater market in Northwest Europe is already tightening. “Some operators are now considering that they may need to go ahead and book the floater of their choice if they’re interested in drilling next year,” she said. Part of the reason is there are fewer rigs that can drill in the harsh environments of the North and Barents Seas. Additionally, Statoil has been able to achieve very low breakevens in the region, including its $25/bbl feat on Johan Sverdrup’s phase 1. This has enabled the operator to forge ahead with its drilling programs. Another example is the Johan Castberg development, also in the North Sea. It had a breakeven above $80/bbl in 2013, but the breakeven for the field is now below $35/bbl.

In Southeast Asia, where most of the world’s floater rigs are actually built, the marketed utilization now sits at a dismal 36.7%. This number has been exacerbated by the newbuild floaters that have been delivered with no contract and nowhere to go. “They just sit there at the yards,” Ms Edralin said. In addition, yards have hired out their empty build slots as parking spaces for idle rigs.

Looking ahead to 2018, Ms Edralin noted that while marketed utilization is predicted to increase, how much of an increase can be achieved won’t be known until operators finalize their budgets for the coming year. “Based on what we know so far, we do expect to see an increase in floater demand in 2018, but oversupply is still going to be an issue next year.”

As of late September, drilling contractors had cold-stacked 64 floating rigs since 2014. Additionally, contractors retired 24 rigs in 2016 and an additional 22 so far in 2017, Ms Edralin said. Larger rig contractors have shown a tendency to announce retirements in bundles. In September, Transocean announced the retirements of six floaters: the GSF Jack Ryan, Sedco Energy, Sedco Express, Cajun Express, Deepwater Pathfinder and Transocean Marianas. In its July fleet status report, Diamond Offshore Drilling announced the retirement of five semisubmersibles – the Ocean Princess, Ocean Nomad, Ocean Vanguard, Ocean Baroness and Ocean Alliance.

While these scrappings will contribute their part in rebalancing the rig market, more retirements still are needed to chip away at the oversupply, especially for floating rigs. In Ensco’s July earnings call, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Carey Lowe noted that there are 70 additional floating rigs worldwide that are strong candidates for retirement. These rigs are all either more than 30 years old or scheduled to roll off contract by the end of 2018, he said.

Mergers and acquisitions that have taken place in the drilling contractor space over the past year could help to hasten additional retirements, Ms Edralin said. In May 2017, Ensco announced it was acquiring Atwood Oceanics. This was followed three months later by Transocean’s announcement that it would acquire Songa Offshore. Having more rigs in their fleets will likely make companies like Ensco and Transocean feel more comfortable retiring some of their less competitive rigs, she added. “We’ve seen this before, even before the downturn, that when one company buys another one, it makes it easier to chop something because they don’t need all of those rigs,” she said.

More floater retirements will certainly be needed before dayrates will rise. The leading-edge dayrate for an ultra-deepwater semisubmersible now hovers between $115,000 and $150,000. For ultra-deepwater drillships, leading-edge dayrates range from $135,000 to $206,000, according to IHS Markit data.

Contract lengths also remain short for the most part, as operators have not shown eagerness to lock in rigs at low rates. Exceptions to this trend include Ensco’s two-year contract with Chevron for the DS-4 drillship to work offshore Nigeria, as well as Transocean’s 15-month contract with Suncor for the Transocean Barents semisubmersible to work offshore Newfoundland and Labrador. In October, Transocean also announced a two-year contract, plus three one-year priced options, for the Deepwater Invictus drillship with a subsidiary of BHP Billiton.

IHS Markit is forecasting that floater availability will start to tighten and push dayrates upward in 2019. “As rig rates move higher, we’ll start to see more long-term contracts,” Ms Edralin added.

Staying in the game

At Pacific Drilling, Mr Acuff said that short-term contracts remain the norm. The Pacific Bora drillship, for example, is working offshore Nigeria under a one-well plus two-well option contract with Nigerian operator Erin Energy. If options are exercised, it could keep the rig working until the end of 2017. The recent contract for the Pacific Scirocco drillship also had only one firm well, with three optional wells, with Hyperdynamics offshore Guinea.

“For the most part, it’s short-term work at the moment,” Mr Acuff said. The only exception among Pacific’s fleet is the Pacific Sharav ultra-deepwater drillship, which is under a five-year contract with Chevron in the Gulf of Mexico until August 2019. The contract was signed before the downturn.

Mr Acuff also noted that he believes operators won’t award many long-term contracts until they gain more confidence about oil prices. “I think we’ll get to the point in our industry to where we can work at $55 a barrel, but there has to be some certainty to the operators. They need to be confident that you’re going to see six months to nine months of pricing in that range before they will commit to major projects.”

In the meantime, drilling contractors are focused on staying competitive in a market where there are far more rigs in need of a contract than there is work to go around. In a normal market, new, high-spec rigs with features that operators are seeking – such as 2.5 million lb hookloads, dual BOPs and managed pressure drilling capabilities – would have a clear advantage when bidding for a contract. However, in today’s ultra-competitive market, there might be several of such advanced rigs available for the operator’s choosing. “I wouldn’t call it an advantage anymore. It’s what you have to have to stay in the game right now,” Mr Acuff said. “We’re competing against the same 10 or 15 rigs everywhere we go, and they’re all newer, sixth-generation rigs like ours.”

Four of Pacific’s seven rigs are currently “smart-stacked.” The company’s smart-stacking approach allows rigs to be idled at below $40,000/day without having to incur capital costs to put the rig into the stack or take it out of the stack.

One way contractors can differentiate themselves is through performance history, Mr Acuff said. A contractor’s safety record and average uptime can help the company stand out in a crowded field when competing for a contract. Pacific Drilling is currently operating at a rolling 12-month average of 98% uptime, he said, which is higher than the historical industry average of 95%.

Contractors are also pushing their costs down as much as possible in order to offer lower rates to operators. Since personnel and equipment represent a large proportion of a contractor’s costs, these are the most effective levers to pull, Mr Acuff said. Over the past two years, Pacific Drilling has worked with its supply chain to reduce equipment and maintenance costs and has reduced the direct operating costs for its rigs from $180,000/day to $130,000/day.

At the same time, the contractor has high-graded its personnel as it has been forced to stack rigs and lay off employees. “Instead of laying off a full crew, we might take the best people from the rigs and try to deploy them elsewhere on other rigs that are working so that we can maintain the best crews possible,” he said. Keeping the best crews on operating rigs can help the contractor maintain its performance history, by drilling wells as safely and efficiently as possible.

At this point, there is little contractors can do to push their costs or dayrates any lower, Mr Acuff said. “The rigs have basically reached their bottom point… We can’t go much lower, or we’ll have to stack them.” Industrywide, rig dayrates have fallen by 60% to 70%, he estimated, while other services like cementing, wireline and completions have come down by only about 30% to 40%. He believes that further cost reductions may have to be found in those sectors.

While contractors cannot push their rates down much further, they can take on additional services on the rig in order to help operators lower their overall costs. Some operators have shown significant interest in this type of approach, Mr Acuff said.

In recent tenders, for example, operators have asked contractors to provide the ROV and casing-running personnel. However, for drilling contractors, taking on additional services means additional risk, as they can become responsible for any downtime related to the additional tasks. This could negatively impact the rig’s dayrate.

“At the end of the day, it comes down to being more competitive and realizing that in order to get this job and utilize my rig, I may take on these services and potentially this risk.” DC