New safety perspective focuses on investigating what goes right

Traditional safety approach views people as the problem; Safety II recognizes people are the strength of today’s complex systems

By David van Valkenburg, AdviSafe Risk Management BV

At a recent team meeting of an investigation into an incident on a production platform, one team member raised the point that the procedure, drafted specifically for the activity, was not followed. This is quite a common comment in current perspectives on safety. This example and the underpinning beliefs about safety will be used in this article to highlight two complementary perspectives on safety – Safety I and Safety II (Hollnagel, 2014).

These perspectives were introduced by Erik Hollnagel, a leading professor in the field of safety.

The article will then introduce ways of using the perspectives in practice. Using different perspectives on safety can increase people’s ability to solve problems, by freeing people from quick fixes and recommendations that don’t tackle the real issues.

Traditional safety focus

The below sums up the most important characteristics of Safety I (White Paper 2013):

• Safety I is about ensuring that things don’t go wrong. The manifestations from a Safety I perspective are the incidents and accidents that companies want to avoid. To explain these unwanted events, causality (the causality credo) is used.

• Causality credo is “the belief that adverse outcomes happen because something goes wrong and that causes can be found and treated.” The outcome can be used to trace back the causes that are attributed to this outcome. The causes are constructed by using two assumptions that drive the way people make sense of these events: decomposition and bi-modal functioning.

• Decomposition means organizations can be decomposed into its components (technical, human and organizational). It’s assumed that because the behaviors of the components are known, something useful can be said about the behavior of the whole system.

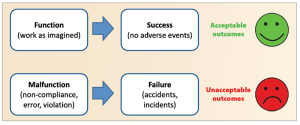

• Bi-modal functioning means the components in the system either function according to specifications or they fail. This is assumed for technical components, as well as for human and organizational components.

• Implicitly, the Safety I assumptions view people in the system as the problem. Technical systems have become so reliable – which is sometimes erroneously used as a synonym for safety – that people have become the most unreliable component of the system and, thus, the most prominent “cause” of failure.

• Implicitly, it follows that success is achieved because all components function as designed. This includes the people adhering to processes, procedures and rules. This implicit assumption is called work as imagined (WAI). WAI is the way that people removed from operational practice (managers, designers) think that work is executed (Figure 1).

The difficulty with Safety I is that the assumptions are not always valid in today’s interconnected world. The assumptions are based on systems that are linear and easy to understand. The current reality is that systems have become so complex that the limitations of the assumptions of Safety I have been reached.

Additional perspective

The limitations of Safety I have fueled the need to come up with different perspectives that are better aligned with current reality. Safety II provides a different way to look at the same problems seen in today’s systems. The below sums up Safety II (White Paper 2013):

• Safety II is about ensuring that things go right. The manifestations are the successes and failures of the system, the spectrum of possible outcomes. To explain the outcome of systems, systems thinking and complexity theory are used.

• In Safety II, it is assumed that the performance of the system is an emergent outcome instead of a resultant outcome. Emergent outcomes arise out of interactions among technical, human and organizational components. Emergence is a term from complexity theory and is a phenomenon that can’t be explained using linear or causal relations. Emergence can be seen in complex systems, such as the ones the industry operates nowadays.

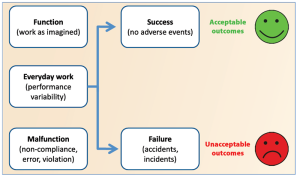

• Safety II assumes that companies should look at everyday performance to explain success and failure. Performance, especially human performance, is variable to match the conditions and demands of everyday operational life. People have to adjust to ensure that things go right. This process usually results in good outcomes and sometimes results in bad outcomes.

• In Safety II, it is made explicit that people are the strength of the systems. They make the system work because they constantly adapt (performance variability). It is what the system needs to function properly.

• From these characteristics, it follows that the process that precedes successes and failures is the same (Figure 2). That focuses our attention on work as done (WAD). WAD is what actually takes place in everyday operational life; it’s the starting point for analysis, assessments, etc.

When looking at system safety using the Safety II perspective, safety is no longer about the absence of something but rather the presence of capabilities (Dekker, 2015) that allow people to anticipate, react and adjust to demands and changing conditions. Decomposition and causality are not able to deal with these emergent outcomes, which undermines some of the current models and methods.

“They didn’t follow the procedure.” This statement holds an assumption about the role of procedures in everyday practice. From a Safety I perspective, the procedure should be followed because that is what creates success. It is then assumed that the “fact” of not following this is at least a contributing factor in the investigation, which will also drive the type of improvements (i.e., training and compliance-oriented approach).

In Safety II, everyday performance and the role the procedure plays in daily practice are examined. Adjustments that have to be made are sought out. It might well be that the procedure doesn’t live up to the real situation, and adjustments are necessary to make it work.

Safety II in practice

WAI vs WAD

The distinction between WAI and WAD can expose the assumptions people have about the functioning of their system. These assumptions also drive the type of improvements they use for the problems they face.

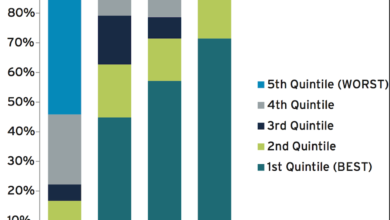

During a project at a Dutch oil and gas company, procedures were being set according to existing standards. To understand the operational life in which these procedures were to be implemented, offshore crew were engaged on topics such as permit to work (PTW). Figure 3 shows that the crews are asked to do a work site visit for every PTW authorized (WAI). In practice, there’s a line of people in the mornings waiting for their PTW to be signed off. Only one platform employee is doing this work. This means that the last person to get their PTW signed won’t start work until the late morning. This is unacceptable since some people are there only for one day, so there is a goal conflict. To solve this, the employee with responsibility to sign off on the PTWs provides PTWs to people he knows, so those people can start their work. He joins the remaining two new people for a work site visit.

This insight is likely not known to the people who drafted the procedure. They are focused on compliance with the procedure even though the procedural requirements are not in line with the demands placed on the people. From a Safety I perspective, the employee is deviating from the procedure. From a Safety II perspective, he is adjusting his performance to meet the multiple and conflicting goals.

What You Look For Is What You Find

Professor Hollnagel also pointed out a phenomenon known as What You Look For Is What You Find (Lundberg et al, 2009). Safety I and Safety II both have their specific assumptions and language that drives what people look for, for example, during incident investigations.

The focus of Safety I is on negative and normative language (Figure 4) that guides what people look for. The rules and procedures serve as a norm to which actual performance is assessed. That is driven by the assumption that the system works because of the rules and procedures.

In Safety II, the starting point is everyday operational life. It’s necessary to have a good sense of how success is achieved everyday, considering the demands and limited resources that characterize daily life at the sharp end. From this perspective, it can be seen where adjustments were necessary to ensure success.

Imagine driving a car. Can someone meaningfully distinguish particular actions and assessments and categorize them as failures or errors when they have had an incident? Or are they constantly adjusting to movements of other cars, sunlight, traffic density and paying attention to signs but at the same time having a conversation with the person next to them? When an incident follows, hindsight can easily blind them from the fact that they behaved just as they do every day on that particular road (Hindsight bias; Fischoff, 1975). But the focus and language of Safety II provides people with the tools to make sense of these things in a different way.

investigate what goes right

An incident investigation was recently completed using the Safety II perspective and the method developed from the Safety II perspective, the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM; Hollnagel, 2012). It was observed that the circumstances in which the incident took place were bad every time they had to perform this activity. But it was also recognized that success was almost always achieved despite these circumstances. At that point, it was proposed to look at this incident in a slightly different way.

Both the process in general and the incident in particular were analyzed. The result was discussed with a group of operational people, which led to recommendations to improve the process. These were based not only on the incident but also on the process analysis. The discussion focused on normal practice, not failures of the people or in the system. The same approach can also be used for successes.

Conclusion

Some theories state that the processes, procedures and rules that have been put in place to make systems safer are actually becoming a risk. Further, examples can be seen of declining (safety) results in terms of traditional measures. Safety I and its methods, tools and measures have taken the industry far in the past decades. But the world is more complex and more interconnected. Using the same measures that have brought these results will only bring more of the same.

The industry should realign its understanding of everyday operational life and start using that knowledge to improve its systems. The focus of organizations will then gradually shift from the traditional command and control approach to improving the resilience and adaptability of the system and especially the people.

The practical applicability of the Safety II perspective is not yet as well developed as for Safety I, but the industry should start to think about the principles and assumptions and consider taking it from theory to practice.

References for this article can be found online at www.DrillingContractor.org.

This article is based on a presentation at the 2014 IADC Drilling HSE Europe Conference, 24-25 September, Amsterdam.