Depth perception

Need for efficiency drives shift toward standardized, automated subsea completion systems, faster product cycles

By Katie Mazerov, contributing editor

The business of finding and producing oil and gas is all about safe and responsible recovery, reliability and return on investment. Nowhere is that mission more important than the world of subsea completions. Today’s subsea completion operations are being ratcheted up a notch to meet another mandate: efficiency. What 20 years ago took 40 or more days from a fixed platform, with multiple trips, using wireline, coiled tubing, tractors and mechanical tools, is now being done in less than half the time using remotely operated tools, automated equipment and new wellhead designs. The vision is having systems that can operate on the seabed floor, eliminating the need for platforms.

To achieve this, operators and service companies are joining forces in a new level of collaboration and upfront planning. High-end solutions for both new and mature fields are hitting the marketplace in record time, bringing greater efficiency and safety to production in wells that are longer, deeper, hotter, more pressurized and more diverse than ever.

“The outlook for the subsea sector is good,” said Tassos Vlassopoulos, marketing director, subsea systems, for GE Oil & Gas, a global provider of advanced production technologies and services. “According to recent analyst data, orders for subsea trees are expected to grow an impressive 25% this year versus 2012.”

Africa is growing in importance, while investments in Brazil, Australasia, the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) and the North Sea are continuing with varying degrees of intensity, he noted. “Key industry challenges include insufficient engineering capacity to satisfy industry demand and technology development to open up the next frontiers of our industry, for example, power and processing. Furthermore, operators are looking to the supply chain to provide wellheads and production equipment that can reliably withstand increasing depths and pressure requirements.”

GE is making a number of large-scale investments, developing subsea equipment rated to 20,000-psi yield and enhancing the loading capacity of the subsea wellhead range to support increased casing loading and fatigue requirements. “We have a structured portfolio, but we are completing the ‘family’ with a deepwater vertical completion variant to help our customers push the boundaries of what is technically possible in terms of field development,” Mr Vlassopoulos said.

In addition to the extensive green-field opportunity in Africa, Australia, Brazil and the North Sea, GE is placing focus on brownfield extensions. “GE is in the final execution phase of a significant brownfield extension for a North Sea operator,” he said. “There is also increasing acknowledgment of the low recovery rates for subsea fields, which operators are addressing with targeted oil recovery programs.”

The need for greater efficiency and cost-effectiveness is driving a shift toward standardized equipment that will lead to improved cycle times, reduced complexity and greater consistency of field procedures, he added. Innovation is also occurring in the subsea processing field to locate equipment, such as multi-phase pumps and compressors normally found on the platform, onto the seabed floor. “An increasing number of field developments will only be economical with the application of subsea processing technologies,” Mr Vlassopoulos noted.

Safety is also a key driver of innovation. “Redundancy has always been a feature of subsea equipment, and we are now seeing even more emphasis and layering in this area per recent safety guidelines,” he said. “Well construction has evolved to include additional risk mitigation steps, with more safety factors, redundancy during drilling and additional casing strings and loads applied to the wellhead system.”

Despite the high degree of innovation, technology adoption has been and will remain cautious, Mr Vlassopoulos indicated. In addition to equipment for higher pressures and subsea processing, subsea control equipment needs the capability to process increasing amounts of reservoir and well data, while the service sector finds better ways to optimize equipment performance and ultimate recovery.

A collaborative effort

New subsea completion tools and technologies also come with a high price tag. Increasingly, however, the endgame is not the cost of the actual equipment but the cost of overall operation. “The economics have totally skewed to reducing the time spent completing wells, which drives a greater level of sophistication in the technology,” said Paul Day, global director of business development, well completions technology, for Weatherford. “Reliability is absolutely key because the equipment in these wells has to work the first time and also work for the life of the well. To that end, we’re finding that the level of operator engagement in the design, development and testing of equipment has grown 10-fold over the last five to 10 years to ensure the integrity of the equipment being installed.”

Whereas in the past, rig costs and actual drilling accounted for the biggest portion of a well construction budget, the current focus is on investing in completion equipment to reduce installation time and eliminate the need for intervention, even on the simplest of operations. Proper completion design and installation can shave millions off of the well construction cost.

“For example, we’ve developed tools that allow us to plug a well without any intervention,” Mr Day said. “Previously, we would have run a well plug downhole on wireline, an operation that would have taken eight to 10 hours, using a rig at a (spread) rate of approximately $1 million to $2 million per day. That $10,000 or $15,000 plug would have cost upwards of $500,000 to install. So it makes commercial sense to use a remotely operated tool that may cost 10 times the cost of the wireline but can save $350,000 to $500,000 in overall well costs.”

Through focused collaboration, operators and service companies are designing and developing tools for specific challenges and bringing those tools to market in a matter of months, a process that 20 years ago would have taken at least two years, Mr Day noted. For a 10-well injector program for a major operator off the coast of Angola, Weatherford deployed a sophisticated open-hole packer, allowing a one-trip sand face completion, cutting days off the completion time and saving the customer $300 million over the 10-well program.

The same operator, for another project in Norway, deployed an advanced water and gas injector, nine open-hole packers and 27 remote sand face tools. The net well savings was estimated at between $10 million to $15 million. A further deployment is planned for this year, with six more to follow. “A great well” as described by the operator provides a foretaste of further advances to come, Mr Day said.

Weatherford is also active in the GOM, which presents a number of completion challenges. “As we look at completing the GOM, technologies that provide improvement in operational reliability, flexibility and cost, and which mitigate risk, are critical,” said Yvonne McAnally, product line director, upper completions, for Weatherford. “For the GOM’s Lower Tertiary, industry doesn’t yet have the tools to develop the more difficult reservoirs, where bottomhole temperatures are more than 30,000 psi. That will drive us to develop new solutions; operators are already asking for equipment that is rated above 15,000 psi and 350°F.”

The company’s new radio-frequency identification (RFID) platform uses tags to actuate downhole tools, such as opening and closing sliding sleeves and barrier valves and set production packers, Ms McAnally said. The RFID-based Keystone platform is a tubing-mounted control module that uses remotely operated tags to actuate multiple tools in the well, significantly reducing trip time. “We’re trying to automate the process and avoid the need for intervention.”

The RFID device tells tools to do things that previously required the use of intervention services, such as wireline and coiled tubing. “We’re developing smarter systems,” Mr Day said. “We’re trying to maintain the same level of reliability we had 20 years ago with simple mechanical tools – and so, far, we’re achieving that goal.”

Backlog of new fields

FMC Technologies also is optimistic about the future of subsea production systems, anticipating a growing new development market and the need to increase recovery from older fields. “There is a significant backlog of new fields to be developed in all regions, and many of the long-producing existing fields are adding satellite fields and systems to support infrastructures already in place,” said Tore Halvorsen, FMC Technologies senior vice president, subsea technologies.

A second trend centers on the service side of subsea completions, driven by the need for increased recovery, maintenance and upgrades of older fields. Many operators have launched dedicated programs to increase uptime of older fields, introduce upgrades to more modern technology and life-extension programs, he noted.

The company also is seeing a push for efficiency, reflecting the increase of marginal fields. “Innovation comes through the need for improved efficiencies and reduced costs,” Mr Halvorsen said. “The practice of running trees on a wire from a small vessel is an example where cost efficiency led to riserless light well intervention systems, moving non-drilling activities off the rig to a mono-hull vessel.

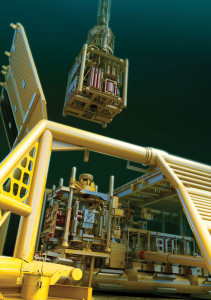

Two Oceaneering Millennium remotely operated vehicles in the Gulf of Mexico are used for maintenance work for a tension leg production platform, the Olympic Intervention IV, which was chartered since it was built in 2008 by Oceaneering.

Among’s FMC Technologies recently launched offerings are a landing string that is a subsea test tree for cleanup and well testing and a non-penetrating annulus-monitoring system to detect pressure buildup outside the main production casing. “We also are developing all-electric systems on the seabed, replacing hydraulic systems with electric actuators, primarily for manifolds but also for subsea trees,” Mr Halvorsen said.

Challenging subsea reservoirs also are forcing operators to rethink their requirements for wellhead systems. “Larger, taller and heavier blowout preventers (BOPs) connected to the wellbore on top of the tree impose more force to wellhead systems,” he explained. “In the old days, reservoirs were shallow, and we drilled straight down and stayed on the wellhead for a few days, with hardly any workover activity required. Now, with long horizontals, ultra-deep wells and the large number of workovers, we have to think differently about how we design the wellhead system, which becomes the anchor point for all activity. We are seeing a clear shift from conventional wellhead systems to rigid lock systems, where the wellhead is rigidly connected to the conductor to better transfer bending load.”

In addition, FMC Technologies has developed a reactive flex joint, a device that can be bolted on top of the BOP to neutralize bending of the wellhead. When the rig moves, the device sets up a negative bending action to minimize the loading on the wellhead itself. It has been tested and is in the application phase.

For the growing HPHT market, the company has introduced a 20,000-psi wellhead. However, as operators consider 25,000-psi and even 30,000-psi wellheads, it is clear the HPHT sector has yet to be fully developed. Particularly on the temperature side, challenges remain, Mr Halvorsen believes. “The BOP drilling business has been elastomeric-based, and that won’t be adequate for ultra-high-temperature fields.”

For ultra-deep wells, “everything from the hang-off shoulders in the wellhead to the casing threads must be reviewed to see how deep it is possible to go,” he added. “Add a salt layer to the equation, and collapsed pressure also becomes an issue with ultra-deep wells.”

Down the road, Mr Halvorsen believes there will be more focus on increased recovery techniques. “The idea of producing 30% of the reservoir and leaving 70% behind won’t be acceptable,” he said. The longer-term vision is to do everything on the seabed floor, eliminating the need for platforms. “Robotics and condition-based monitoring will play a key role in maintenance on the seabed, where prediction of maintenance will be essential for quick replacement of modules. This will be especially true in extreme environments, such as the Arctic, where operators will have to access fields beneath heavy ice caps.”

A great enabler

A key aspect of the industry’s ability to go into deeper and more challenging reservoirs has been the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) that, when outfitted with the appropriate tools, can perform tasks that promote safety, asset integrity and reduce costs by providing completion support to ensure reliable production through the life of the well.

“The ROV has been a great enabler of the deepwater boom that the industry is engaged in right now,” said Clyde Hewlett, senior vice president, subsea projects for Oceaneering International, a global provider of ROVs, specialty subsea hardware, installation services, asset integrity management and other services, with a focus on deepwater applications. “At the end of the day, the only way to really know what is happening under water is with an ROV.” Since it was first introduced as an experimental technology in the 1970s, the ROV has evolved into a necessary tool for delivering vision and stereo for depth perception, manipulating large objects, clearing debris, deploying sophisticated telemetry and other subsea tasks.

“We’re increasingly seeing two ROVs on a rig to provide redundancy and to perform specialty tasks, such as those associated with the BOP,” Mr Hewlett said. “For example, if control is lost in the normal remote-control BOP operation, the backup ROV can be used as a secondary means of keeping the BOP running according to specifications, so operations can proceed. Otherwise, the operator might have to pull the BOP.” A second ROV also can be used for more general purpose work, such as checking the wellhead or surveying the riser.

One of the ROV’s most important functions is enabling remediation services when there is a problem after the well has been completed. Flowline remediation tools, for example, can address issues such as hydrates, which are common in deepwater environments due to the cold temperatures at depth. “Gaseous hydrocarbons in the presence of water turn into ice, or hydrates,” Mr Hewlett said. “An ROV with a suite of hydrate remediation tools, such as hydrate skids, can disassociate the hydrates and open up the flowline to re-establish production.”

Such services increasingly are being provided from separate vessels, often at a fraction of the cost of a deepwater drilling rig. “One of our objectives is keeping the rig doing what it does best, drilling and completing the well, while doing other work from smaller vessels using ROVs and specialty tools.”

Another important consideration in the subsea sector is making equipment capable of operating at water depths of 10,000 ft or more. In that regard, Oceaneering provides installation workover control systems (IWOCS) during the final phase of a downhole completion to perform such tasks as landing the tubing hanger. “We can run IWOCS off the side of the rig, away from the drill center, so activities can be done in ‘hidden time,’ outside the critical path,” he explained.

Asset integrity, the assurance that equipment is functioning properly, efficiently and safely is an area that will grow for subsea fields, Mr Hewlett believes. “Just because we can’t see the equipment, we know it’s there, and we need to know that the integrity of those tools is good,“ he said. “As industry continues to push into ultra-deepwater environments, one of the next big challenges will be to demonstrate that the tree, the manifolds, flowlines, umbilicals and other equipment can be inspected and monitored in such a way that every stakeholder has the assurance those assets have integrity.”

Keystone is a trademarked term of Weatherford.