KOC program takes systematic approach to major accident hazards

Implementation of process safety management borrows from chemical process industry

By Garry Gopaul, Kuwait Oil Company

Catastrophic plant and equipment failures involving significant releases of hydrocarbons and hazardous chemicals have resulted in some of the most severe industrial accidents. In April 2010, the world was again reminded that drilling operations are among the most hazardous in the world, with the potential for major accidents. The Macondo incident resulted in 11 lives lost, almost 5 million bbl of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico over an 87-day period and significant financial loss.

It also served to remind us that while many good companies are expending significant efforts on personal safety programs, which are essential for safe drilling operations, these alone cannot effectively manage major accident hazards and risks.

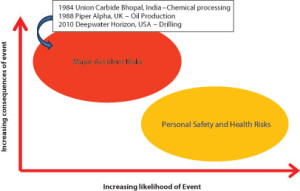

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between personal safety and major accident risks and lists a few previous major accidents.

The chemical process industry has recognized the value of process safety management (PSM) and has been using it for some time to manage major accident risks. The E&P industry can look to this industry to learn valuable lessons on PSM implementation.

This article looks at how PSM implementation, aimed at reducing the potential for major accidents, has commenced at an onshore E&P operation involving more than 60 land rigs comprising both local and international drilling contractors and service companies, and discusses the challenges of integrating the culture of process safety into existing operations.

Is this necessary?

There are many definitions for PSM by different organizations that go into varying detail. A simple explanation put forward by the UK HSE in HSG 254, “Developing Process Safety Indicators,” is as follows:

“PSM is used to describe those parts of an organization’s management system intended to prevent major incidents arising out of the production, storage and handling of dangerous substances.”

Many organizations involved in drilling and well servicing are reasonably aware that handling “dangerous substances” is part of everyday operations and recognize that a history of no previous major accidents is no guarantee of the same in the future. This, coupled with the fact that the losses associated with major accidents in this industry are so significant that they can drastically affect the viability of a company, points to the need for this.

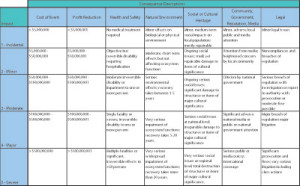

Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) has identified operational excellence as one of its 2012-13 strategic objectives and developed measures for this (Figure 2). To achieve this, the management system must cover not only the high-frequency, low-consequence risks but also the low-frequency, high-consequence ones.

Low-consequence risks are typically targeted by personal safety programs and measured under the umbrella of “strengthen our commitment to HSE” at the drilling and other groups level.

High-consequence risk actions, identified from major accident hazards, are captured in enterprise risk management at the company level. These, along with other similar business risks, are tracked as a measure called risk index under “strive for excellence in performance.”

To measure overall implementation of the PSM three-year plan, a “PSM index” was introduced into the balanced scorecard of each group, with a target of 95% closure of actions. Integration of PSM into the key performance indicators of the business scorecards is important to provide impetus to move forward.

Implementation challenges

PSM began in KOC around 2005, when it was called integrity management, with the primary focus on oil and gas production facilities, storage facilities and transit pipelines. At that time, the focus was on preventing significant leaks from transit pipelines and processing facilities in a systematic and proactive manner.

Additionally, the potential for major accidents and the impact this would have on KOC’s overall operations and growth strategy was recognized. Subsequently, PSM implementation became mandatory for the exploration and production development (E&PD) directorate, responsible for drilling operations, in 2009.

Some of the challenges faced in building the PSM culture are:

• Absence of organization and support provided by a mature regulatory regime experienced with driving major accident hazards.

• Good HSE performance in industry is still largely judged by occupational incident frequency rates, such as LTIFR and TRIR, which target the high-frequency, lower-consequence incidents, or working a large number of hours/days without recording a LTI. However, even when frequency rates show steady decline or safe working hours increase, which both reflect improved safety performance, they cannot be used as indicators of good risk management associated with major accident hazards.

• In KOC, drilling and well servicing operations are conducted via rig contractors and service contractors. KOC has no direct ownership, maintenance and operations of equipment, or management of personnel similar to its production facilities. Direct control can facilitate enhanced implementation of PSM.

• The drilling groups have 60-plus rigs in operation. This, along with the service contractors, represents a very large fleet to engage in PSM implementation.

• A mix of local and international drilling and service contractors, each with different cultures and standards.

• Most contractors have no structured standards for assessing or managing major accident hazards. The complexity of PSM implementation requires a structured management system approach coupled with active management involvement.

• Adopting PSM to drilling and service company operations when the standard requirements are aligned mainly for process plant type operations.

• Perception that PSM is largely an HSE program led by HSE personnel, which led to a lag in involvement by operations and maintenance personnel.

Commencing implementation

KOC developed a PSM standard to provide expectations for implementation in all directorates of the company. The PSM standard is a large document with many requirements, and the challenge was to identify what should be the first steps on the journey. Essential for setting up the structure and supporting PSM going forward was assignment of accountabilities.

Establishment of PSM accountabilities were:

• The first appointment was assigning a single-point accountability for PSM implementation. This was handed to the deputy managing director (DMD) for the E&PD directorate.

• A management representative was then appointed by the DMD to lead a PSM implementation committee, consisting of representatives from each of the groups in the E&PD directorate.

• Groups were asked to develop three-year rolling plans (2009-12). This consisted of a combination of mandatory and optional requirements. Mandatory requirements included establishment of safety-critical equipment (SCE) registers, emergency response plans to include major incident risks, etc. Optional requirements were selected based on each team’s assessment.

• Roles and responsibilities for key supporting positions were developed – engineering authority and two technical authorities (drilling operations and drilling materials).

• Periodic awareness sessions were held with group representatives to clarify requirements and discuss plans.

Focus on SCE

A mandatory KPI for both the drilling and service contractors was the requirement to have a register of all SCE. The introduction of major accident hazards and SCE to contractors was fairly new, and two issues arose that had to be addressed:

1. All categories of safety equipment were being classified as SCE, and this was undesirable as it could lead to inadequate focus on SCE during periods of resource limitation.

2. The concept of “critical spares,” necessary for continuity of operations, was in some instances mistakenly included under the category of SCE.

To facilitate a better understanding of PSM in drilling and service company operations, a simple PSM handbook was developed. The main focus of this was to understand the concept of major accidents and bring awareness around SCE.

For 2012-13, approximately 75% of rigs have declared they will maintain SCE registers as one of their PSM KPIs.

For the service contractors, all four cementing and four logging and perforation contractors have established SCE registers.

As E&PD drilling operations are undertaken by contractors, it is fundamental to receive assurance that rig and service contractor personnel understand the potential for major accidents, that they can make informed decisions about the effectiveness of SCE and that they will be able to take appropriate actions to provide assurance of functionality. This has been recognized as a key area of focus and will have to be monitored by introducing the requirement for adequate performance standards for SCE.

The Deepwater Horizon Investigation Recommendations, published by BP on its website, reinforces the focus on SCE. Their recommendations include:

• Establishing key performance indicators for SCE;

• Updating requirements for subsea BOP configurations; and

• Establishing in-house expertise for subsea BOP and BOP control systems.

The flowchart in Figure 3, taken from the KOC PSM standard, illustrates the approach that will be applied to the management of SCE.

Inclusion in enterprise risks register

At the company level, any risk that is so significant it could adversely affect achievement of KOC’s overall business strategies (enterprise risks) and the associated actions are individually tracked. In 2009, the E&PD directorate was required to commence reporting on its “enterprise risks.” In the Enterprise Risks Register (ERM) of very high/high risks, SCE risks have been captured under “integrity and degradation of performance of well control equipment.”

Figure 4 shows the ERM risk-ranking matrix, and Figure 5 describes the consequences.

Routine updates on the progress of actions are provided by the ERM team to KOC upper management. As mentioned, adequate control of enterprise risks is also a measure of “operational excellence” and tracked as a risk index.

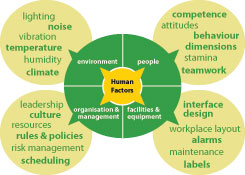

Human factors

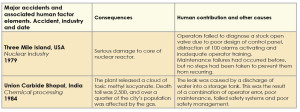

The aviation and nuclear industries use the study of human factors extensively in developing programs to avoid incidents associated with operator error. Figure 6 lists two familiar major accidents with acknowledged human error as contributors.

While these are not associated with E&P operations, it is clear the human factor contributions can also be common to E&P. These usually manifest themselves as unintentional actions by workers due to incompatibility:

• Physical match – people and the work environment; or

• Mental match – information and decision-making requirements.

Recent interest in human factors has commenced in KOC with identification of these contributors for incident investigations. There is good value that can be obtained in drilling operations by integration of human factors into major accident hazards programs due to their profound impact.

Next steps on the journey

The following have been identified as key contributors to move forward with PSM implementation in a sustainable manner:

People

• The competence model for safety, drilling and petroleum engineers must include major accident hazards and PSM, specifically related to drilling and well servicing operations.

• Establish competency requirements for contractor personnel with responsibility for maintenance and testing SCE.

• Identify “safety-critical activities” for drilling operations, i.e., activities that are required to ensure the barriers are in place and working effectively, and develop competency requirements around these for drilling personnel.

• Consider human factor contributors in analysis of major accident hazards.

Process

• Introduce and use specific tools, e.g., failure modes and effects analysis, fault tree analysis, event tree analysis, HAZOP, etc, to assist with SCE evaluations and incident investigations.

• Establish a database of PSM learnings from incidents, both internal and external.

• Include PSM audits for drilling and service company operations in the HSE audit register.

• Build major accident drill scenarios for rig/rigless operations focused around failure of SCE.

• Develop emergency response plans to cover the hazards of events at adjacent facilities, e.g., gathering centers and gas booster stations that could result in major accidents at rig sites and vice versa.

Plant

• Establish management of change tracking and coordination for any change to equipment, or purchasing remanufactured equipment by drilling and service companies.

• Work closely with ERM team on verification of ERM actions for SCE.

• Request the development of performance standards for SCE by contractors after it is confirmed their SCE registers have been adequately developed and awareness of impact of SCE on major accidents is in place.

Key learnings

The E&PD directorate is three years into the journey of PSM implementation, and, as in all program implementation, there are lessons that have been learned along the way. Below are some important lessons learned:

• Sell the story that PSM complements the occupational safety programs and allows a picture of the entire risk profile. Show where it fits in the strategic measures.

• 18002, the Guidance Document to OHSAS 18001, advises that organizations must ensure that their hazard identification, risk assessment and risk control processes must be “suitable and sufficient” to all their risks. Any mindset of “we never had a major accident or won’t have major accident hazards” needs to be removed and replaced with, “we need to identify major accident hazards and manage the risks effectively.”

• Communication on PSM should be specific to drilling operations – use language, equipment, positions, KPIs, training, guidelines, etc, not those specific to chemical process plants or production operations.

• Understanding what SCEs are and recognizing them as barriers to major accidents is essential. The PSM handbook that was produced targets this.

• Continuous focus on reinforcing and confirming key concepts, such as SCE, may be necessary in the early stages of implementation.

• Learn from “experts” who have started the journey. The UK HSE and other organizations that have experience can provide valuable information on implementation.

• Auditing of maintenance and certification of L&P and cementing contractors SCE annually has been a success.

• Share PSM-related incidents and recommendations to build awareness of the importance, e.g., IADC alerts, internal HSE alerts.

• Multidisciplinary involvement is required for PSM, not primarily HSE personnel. Get operations and maintenance personnel from drilling and service contractors involved in early stages.

• The PSM index referred to earlier represents the percentage of PSM actions closed and is a leading indicator. Identification of a suitable lagging indicator is equally important because organizations typically tend to “respond” to these with increased attention and efforts. We cannot, however, set tolerance values based on major accidents or near-misses, similar to what is done for occupational incidents with LTIFR, TRIR, medical cases, etc. Thus, there is a need to carefully consider establishing suitable lagging indicators, which reflect early warning of major accidents due to deterioration of controls for people, process or plant.

Summary

We cannot address major accident hazards in the same manner as personal safety hazards. The costs arising from major accidents are much too great. We need to follow the systematic approach of the chemical process industry but fashioned to drilling and service company operations and recognize the long-term commitment required for this.

This article is based on a presentation at the 2012 IADC Critical Issues Middle East Conference & Exhibition, 4-5 December, Dubai.

Dear Garry,

We are an enterprise asset management company based in Perth,Australia. We offer asset register services, safety-critical Element Analysis consultation and equipment performance standards review for the purposes of enhancing MAE control measures.We would appreciate it if you could provide us with information on some of the relevant work tenders by KOC.