Rotary steerables: Cost, reliability still key; higher dogleg capability, downhole motor integration also on asking list

By Linda Hsieh, assistant managing editor

Once upon a time, the land drilling industry dreamed of a rotary steerable system that would replace the downhole mud motor. The system would provide accurate downhole directional control while rotating the drillstring at all times, thereby boosting ROP and improving efficiency. It didn’t have to be fancy, but it had to be low cost.

At least, that’s what the industry thought it wanted. It turns out, however, that just because onshore drilling is a lower-cost market doesn’t mean it necessarily needs only lower-specification equipment.

“A few years ago … the industry was saying they would accept limited functionality, limited dogleg capability. They weren’t really interested in sensors. They just wanted to take the mud motor out of the operation,” said Jerry Keen, Weatherford International business unit manager for US drilling services. “Well, that’s changed. Now they want the same systems we have offshore. They just need us to figure out a way to build those systems cheaper” other than by stripping out functionality.

Especially when it comes to dogleg capability, service companies are finding that land-based customers often have even higher requirements than offshore clients. Due to the advent of unconventional resources and horizontal drilling, achieving build-up rates of 6° or 8°/100 ft is no longer enough. In fact, land-based operators are pushing for rotary steerables to go as high as 15°/100 ft so they can get the curve section built a lot sooner.

“They moved the target on us a little with respect to dogleg,” said George Sutherland, global business development manager for Halliburton’s Sperry Drilling. “Many of the shale applications in North America require that we increase our dogleg capability above 10°/100 ft, which has challenged us to make rotary steerables meet that demand.”

Mr Sutherland explained that doglegs well above 10°/100 ft are achievable now in smaller hole sizes like 6 in., but where it’s really required is in the 8 ½-in. and 8 ¾-in. sizes.

Operators also are asking for consistency in the doglegs, said Mike Williams, global accounts manager for Schlumberger’s Drilling & Measurements group. “The new grail in terms of that is, ‘Give me a system that gives me X dogleg regardless of the formation type.’ That’s not easy, by the way. … I think there’s a little bit of work to do in that for everybody.”

LAND UP-TAKE

Even with current capability limits, however, rotary steerable technology has been able to achieve significant performance improvements for land projects.

In some onshore horizontal wells, rotary steerables have been able to double the length of lateral that can be achieved, Mr Keen pointed out. Especially when used in combination with advanced LWD technologies, improvements can be significant.

He referred to a horizontal, updip drilling operation in Montana that his company recently completed using a rotary steerable system driven by a mud motor, and in conjunction with a triple combo LWD system; days were saved in the overall operation. “We basically added 2,000 more feet to the average lateral that (the operator) hadn’t been able to achieve in the past,” he added.

Achievements like that are why land-based customers who wouldn’t even discuss rotary steerables a few years ago are now willing to try the technology in their own drilling programs. Schlumberger, for example, noted that rotary steerables now account for 50% of its total footage drilled, both onshore and offshore, up from 20% five years ago.

Perhaps it’s because the market penetration of rotary steerables offshore is already quite high, but Mr Williams emphasized that “land is where the increases are coming.” Even though the number of active land rigs in North America has fallen substantially since the global economic recession began, the number of rigs moving to horizontal drilling from vertical drilling continues to increase. Moreover, land markets outside North America are picking up rotary steerables as well – in places like China, Saudi Arabia and Russia. “It’s hard to find a market now where we can’t justify rotary steerables in some applications,” he continued.

Adding to the demand for directional-control rotary steerables on land is the growing need for vertical-control tools that can keep well deviation below 0.5° or 1°. These tools allow the driller to place a higher weight on bit to increase ROP without having to worry about deviating from vertical, Mr Sutherland said. “If you can drill a very straight and smooth vertical portion, you don’t have to deal with a lot of torque and drag issues that can hurt your ability to drill your curve and extend your laterals,” he remarked.

Interestingly enough, the vertical-control market that started onshore is also shifting to offshore, particularly in deepwater, where true verticality can be very desirable, Mr Williams said.

In one Anadarko deepwater well in the Walker Ridge area of the Gulf of Mexico, Schlumberger provided its rotary steerable system with a PDC bit to vertically drill the 26-in. hole section. A total of 2,166 ft, including 733 ft of salt, was drilled through to reach section TD with a single BHA and a hole inclination of 0.19°. This allowed the 22-in. casing to reach bottom on the first attempt.

COST, COST, COST

Despite significant technological progress and impressive growth in operator acceptance, the fact is that rotary steerables’ onshore market penetration remains quite low. As Mr Keen put it, land is a market where “the mud motor is still king.”

The obstacle – not surprisingly – is cost.

Rotary steerables have always been more of a “high-end” tool, understandable considering the complicated electronics and functionalities involved. Yet costs to deploy the technology have been able to come down steadily since its early days due to a variety of improvements, for example, in tool design and manufacture and ways to repair/maintain the tool faster and change hole sizes faster. Market competition and, more recently, the overall market slump also helped to bring prices down.

But has it been enough?

“We’re still playing at the higher end of that low-cost market. We’re not playing at the low end of it yet. Day in and day out, our clients request a low-cost rotary steerable,” Mr Williams said.

And “low cost” does not mean fewer functionalities, as was pointed out previously. It doesn’t even necessarily mean cheaper.

“If ourselves and our competitors really envisage the day that rotary steerables cover the whole gamut of applications – land, offshore, high tier, low tier – then we have to make it cost-efficient. Notice I didn’t say cheap,” Mr Williams said.

Comparing the cost of rotary steerables with the cost of mud motors will always be a futile effort because it’s unlikely rotary steerables will ever become cheaper on a unit-cost basis. New technologies are also coming out to make conventional slide-drilling more efficient, such as a system from Canrig that rocks the drill pipe back and forth to break the friction while sliding.

So, instead of tackling the issue of cost through cost, service companies are coming at it through performance and efficiency.

If using rotary steerables can help an operator extend his lateral and shave days off total drilling time compared with conventional slide drilling using a steerable directional motor with a bent housing, then the value-versus-cost argument can begin to tilt in favor of rotary steerables.

In the technology’s early days, low levels of reliability meant efficiency was low as well. Now, reliability has reached a point where rotary steerables are “not a gamble anymore for the operator,” Mr Williams remarked.

It’s also worth noting that every service company interviewed for this article emphasized their focus on reliability. It’s something they’ve worked hard to improve, and they’re proud of the strides they have taken.

“A lot of things we do in terms of making improvements to the products are not necessarily apparent from product features alone, but what is apparent is that we constantly and consistently improve our reliability,” said Baker Hughes product line manager, automated drilling systems, Mark Freeman.

His company constantly tracks reliability through metrics like MTBF (mean time between failure) and percentage of nonproductive time, although he declined to provide specific numbers, citing the industry’s lack of a recognized common metric for reliability. It’s still an industrywide obstacle that makes it difficult to make direct comparisons between different companies and different systems.

PUSHING THE ENVELOPE

Directional drilling technology has come a long way since the days of no MWD, no mapping of the wellbore and spotty steering control. Nowadays, a variety of sensors and tools can be used to provide information about formation characteristics and downhole dynamics so the bit can be strategically steered within the reservoir and drilling parameters can be optimized.

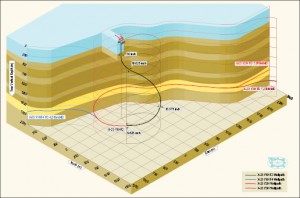

“Our directional drilling is really more about drilling optimization than trajectory control now,” Mr Sutherland said. “Directional drillers are focused on providing overall efficiency rather than just focusing on keeping the well on track. Lateral trajectory control is now much easier, with recently developed deeper-reading LWD measurements routinely allowing us to precisely place laterals 100 percent within zone.”

Companies also continue to push their systems’ operational envelope, both onshore and offshore, through advances in sealing technology, mud pulse telemetry, preprogramming capabilities and downlinking.

Additional benefits are coming from the enhanced ability to model drill bits and bottomhole assemblies, the improved side-cutting capability of PDC bits, and overall better bit designs that inherently produce less vibration.

“Long-gauge bits have made big improvements in hole quality and vibration reduction,” Mr Sutherland said. “(They) are proving much more effective at drilling smoother, less tortuous wellbores.”

Expansion of rotary steerable systems’ available hole sizes is also giving operators more options in well design. Especially offshore, operators are showing a growing interest in rotary steerables for top-hole sizes. “I would guess the market in the big hole sizes has doubled or tripled over the last couple of years,” Mr Williams said. Part of that is due to the increase in deepwater drilling projects. But also, operators are recognizing that they can “make the well plan simpler further down by doing some work at the top, i.e., rather than just drilling a vertical hole,” he said.

Of course, the dogleg capability that’s needed in the bigger hole sizes isn’t as high as with 6 in. or 8 ½ in. tools. “There is no need for 15° doglegs in 26 in. hole or 28 in. hole, but if we had a system that could do 5° in that size hole, then the whole market would change,” Mr Williams said.

On the other end of the scale, smaller-size tools below 6 in. are also shaping up to be “a boom market” due to the increasing number of re-entry wells being drilled. In the North Sea, for example, slim-hole rotary steerables as small as 3 7/8 in. have been helping operators save costs by going through existing production tubing and sidetracking out the bottom. They are also being used to go through deepwater Christmas trees so they don’t have to be pulled, Mr Williams said.

The challenge with smaller hole sizes lies in having the right size tool, because there are no standard sizes once you go below 6 in., Mr Williams said. “So how do you build a system to cover the vast number of weird and wonderful hole sizes? That is a challenge.”

MOTOR-DRIVEN SYSTEMS

Oddly enough, even though rotary steerables were initially developed as a means to take mud motors out of the equation, operators now want to put them back in. As a result, running rotary steerables in conjunction with downhole mud motors is now providing significant performance improvements in a variety of applications.

The advantages are many, but the primary benefit is in providing more power to the bit, which increases ROP. This can help to extend lateral sections, as well as push the limits of extended-reach drilling.

“Over time, we recognized the opportunity, especially drilling in extended-reach applications, where you might be torque-limited with what the top drive or rig can deliver to the bit at the end of the drillstring,” Mr Freeman said.

The same can be said for long horizontal wells onshore, where motor-driven rotary steerables are being deployed on smaller rigs that might otherwise be underpowered for the type of wells planned.

Service companies stress that using this tool combination isn’t as simple as putting a mud motor on top of the rotary steerable. One issue to consider is that the bearings and transmission in the motor section would need to handle the extra weight of the rotary steerable. Using a normal motor that might not be able to handle the extra torque and load could be asking for trouble.

There’s also the issue of real-time communications. How will information from the rotary steerable – inclination, azimuth, gamma ray, etc – get passed over the motor section to the MWD and sent up to surface? Is it better to hard-wire the motor or to use electromagnetic “short hop” telemetry?

“If you’re going to put the mud motor back in, you have to rethink the whole operation. ‘Do I need to put the whole mud motor back in, on top of the rotary steerable? Or can I just come up with a way to rotate the mud motor 100% of the time?’ ” Mr Keen said.

With the industry continuing to push wells to extreme depths both on land and offshore, service companies see the motor-driven rotary steerable as something that could become a major enabling technology in the coming years. Mr Williams, for one, believes that market up-take will be rapid and substantial. His company’s motor-driven rotary steerable system already accounts for approximately 20% of the company’s total footage. “My feeling is it will be over 50% within the next two or three years,” he said.

ROTARY STEERABLE LINER-WHILE-DRILLING

Enhancing the capability and application range of rotary steerables this year was the introduction of a rotary steerable liner-while-drilling system developed jointly by Statoil and Baker Hughes. With this system, the liner is attached to the BHA and drillstring while drilling the directional program. Once TD is reached, a drop-ball system is used to unlatch the setting tool. The BHA and drillstring can then be pulled out of the hole, leaving the liner in place.

The system is currently available with a 7 in. liner system for 8 ½ in. hole and a 9 5/8 in. liner system for 12 ¼ in. hole. Statoil has deployed both sizes in the North Sea, starting with the larger-size version in April 2009 off of the Brage platform.

The second deployment, of the smaller-size version, was just completed in January on the Statfjord Field. Mr Freeman remarked that the operation “went off without any significant issues, what we learned will be incorporated as improvements to the system. It was definitely a success.”

HPHT

Although the world’s current HPHT market can only be characterized as tiny, industry trends continue to point to the need for higher-spec HPHT tools, including rotary steerables. “There has been a push from the operators. They’re showing us areas they’d like to develop (where) they’re being challenged with temperature and pressure,” Mr Sutherland said.

He continued: “The greatest challenge we face today is probably the higher temperatures and pressures. Keeping motors and rotary steerables in these environments is really pushing the envelope in the industry … and of course you have to have MWD and LWD systems to match what your rotary steerable can do.”

While today’s downhole tools can generally operate in environments up to 175°C and 25,000 psi, operators are “already asking us to push the envelope even further,” Mr Sutherland said, a sentiment echoed by the other service companies.

The problem with pushing even further, particularly on the temperature side, is the significant amount of investment needed for research and testing. Certainly there are many potential HPHT markets – even onshore North America, some wells in the Haynesville and Eagleford shales can get above 300°F (150°C). Yet, actual existing markets for HPHT field exploration and development still remain quite small.

To this end, Mr Williams voiced a concern that many in the service industry are likely thinking too: “HPHT research is a lot of investment, but you can’t run alone with it,” he said. Unless every part of the industry is working on their little pieces of the overall HPHT puzzle, the few companies that do venture forth could end up with very expensive pieces of tools that can’t be used because other supporting HPHT technologies aren’t available.

Despite these and other concerns, service companies are continuing to invest in HPHT research and development at the request of their customers. One way they justify the investment, Mr Keen said, is by understanding that high temperature is also the next evolution for LWD technology, which shares many common electronics with the rotary steerable. “So if you’re going to upgrade your LWD system, then you’ve already done half the work of upgrading your rotary steerable system as well,” he said.

Companies can also look at their investment from the reliability point of view, Mr Williams suggested. “If you can get a system to work at 200° plus, then the reliability at 120°C to 150°C almost goes up by default. … That’s how we justify it,” he said.

Having one or more operators sign on during a technology’s early development phase is certainly another way to encourage R&D in this area. Mr Sutherland pointed to the agreement that Sperry made with TOTAL E&P and others in 2008 as one good example. The agreement is allowing Halliburton to work toward developing an MWD system capable of operating in temperatures up to 230°C (450°F).

COMING SOON…MAYBE

Looking at the future of rotary steerables, a few trends are emerging that could bring step-changes to the way directional wells are drilled and rotary steerables are run: wired pipe, remote operation and closed-loop automation.

First is wired pipe, which can provide significantly larger bandwidths than mud-pulse telemetries. The latter has seen its own advances that have already removed major communication roadblocks in deep and ultra-deep wells. In fact, except at extreme depths, the industry doesn’t even use the full bandwidth available in today’s wells, Mr Williams said.

And now, wired pipe is coming along so that even more data can be transferred at even faster rates. While the potential benefit is enormous, Mr Williams said, “I’m not sure we know as an industry exactly what we’re going to fill it with yet.” Reliability issues at 30,000-40,000 ft will also have to be addressed before the industry will fully accept wired pipe, he continued.

A second trend comes from directional drilling being conducted from remote locations – commanding the BHA not from the rig but from, for example, a separate operations center based in another country or on another continent. While this is a technology still in its infancy, Mr Keen emphasized that it’s achievable and, in fact, is already being done in some areas of the world. “With the data transmission we have these days, some RSS and LWD/MWD tools can receive downlink command instructions from just about any point in the world. … It opens up a new set of scenarios for how we do our business in the future.”

Finally, there’s the emergence of closed-loop automation of directional drilling, where control of the tools are given over to computers feeding off of real-time downhole data. Mr Freeman said this is definitely a topic that more and more people are talking about and a subject gaining increased interest.

Yet as a matter of actually getting implemented on today’s rigs – the momentum for that is still rather lacking.

“I don’t think the industry is ready to program the well path in and let the system go. Much as some will tell you they are if we have (the technology), I’m not convinced,” Mr Williams said.

Currently, his company is trying to help the industry transition toward full automation via an electronic “adviser” that monitors real-time downhole parameters. When the “adviser” believes there is a better setting that can be used to achieve the directional goal in the wellbore, it will suggest the new setting to the directional driller. The directional driller then gets to choose whether to take this advice or not.

This way, Mr Williams explained, the machine is not working independently of humans, and humans get to retain the control they’re not ready to let go of.

This might seem like only a baby step toward full drilling automation, but without taking baby steps, directional drilling and rotary steerables technology wouldn’t be where they are today either. They just took a few decades to grow up.

Click below for a Geo Pilot animation from Sperry entitled “Wellbore Placement in Real Time Animation.”

[youtube 3DkqdcfRIu8]

Question to author:

Would R-S be more economical than MM in floating drilling where dayrates are $400,000+

Mike

281-206-8412