Petrobras takes human factors approach to improve safety and performance in deepwater drilling

Two rigs working on complex pre-salt project go from bottom to top in performance by dumping blame/punish culture and adopting learn/improve culture

By José Carlos Bruno, Petrobras

This article discusses the evolution of the safety and operational performance of two ultra-deepwater drillships owned and operated by Seadrill and working for Petrobras over four years, from February 2015 to February 2019, and how the systematic application of human factors concepts and tools helped to create a much safer environment and an outstanding operational performance improvement.

In 2014, Petrobras entered into a consortium with four other major oil and gas corporations to constitute a joint project team (JPT). The objective was to develop one of the world’s most significant fully integrated ultra-deepwater projects in the petroleum industry 200 km off the coast of Rio de Janeiro state in the Brazilian pre-salt area.

From the very beginning, and having the Macondo disaster yet fresh in mind, the JPT decided that a project of such magnitude should be carried out under the highest safety and operational standards – much higher than what had been practiced in the industry so far. It would require a massive effort to ensure excellence in both safety and operational standards.

The project would require dozens of wells to be drilled, completed and connected to production platforms located in water depths around 2,100 m. It represents an immense enterprise from both financial and operational perspectives. Developing and operating an oilfield of this size costs billions of dollars and exposes millions of human-hours to one of the most hazardous and complex working environments on Earth.

In mid-2015, the JPT director formed a team tasked with giving the HSE department a more operational focus. At the time, the exploratory drilling campaign had just started, with two state-of-the-art seventh-generation drillships, the West Tellus and West Carina, which began in Q1 and Q2 2015, respectively.

The two rigs, however, did not start well. They started by ranking in the last quartile among floating rigs working for Petrobras. It was recognized that immediate efforts were needed to improve their operational and safety performance.

Fortunately, the nature of this joint venture allowed a certain level of experimentation. Therefore, an ambitious pilot program with a focus on human factors was developed and approved by the JPT, with the primary objective of enhancing the level of maturity of the safety culture to guide operations. As a framework, it was also decided to initially follow the recommendations issued by IOGP (Reports 435 and 452) as a pathway toward safety excellence in offshore operations.

Therefore, the safety culture program followed the highly reliable organizations (HRO) theory, with a focus on highly complex socio-technical systems. Three pillars constitute the basis of the HRO theory: trust, learning and accountability.

Drilling an oil well, particularly in deepwater environments, is a highly hazardous and complex activity. Such complexity requires the driller to be skilled at adaptation and human intervention in order to keep drilling operations running efficiently and safely. However, even after Macondo, there was still a strong belief among many organizations in the oil and gas industry that safe behavior programs are the best approach to safety. Unfortunately, such an approach inhibits workers from locally adapting to normal variability and closing the gap between the work as imagined and the work as done.

Industrywide, such adaptations were not only unacceptable but equal to violations subject to disciplinary measures. Therefore, meaningful safety interventions were designed to control the behavior of people on the front line through rigid compliance with rules and regulations.

In the field of human factors, this is known as the “old view of human factors.” Safety performance is reactively measured by the number of incidents, mainly personal accidents (e.g., behavioral deviances and injury rates). There is a belief that preventing these minor high-frequency incidents will also predict and prevent major catastrophic events.

It was not difficult, then, to realize the large gap between the enormity of this challenge and the available repertoire in the field of safety science, particularly human factors and systems safety. These were concepts that were barely known by most of the leadership in the oil and gas industry, especially back in 2015.

Human error is normal. Learning how the work is done is the best approach to help people work safely, rather than fixing things when something goes wrong. Such concepts synthesize the “new view of human factors.”

How could the team develop an effective safety culture following HRO principles if all the organizations directly involved in the deepwater drilling operations – the operator, partners and the drilling contractor – had their safety management systems based on the traditional approach of command and control, which sees human error as the primary cause of accidents and which makes people a problem to control? In summary, how could the team step away from a deeply embedded “blame-and-punish” culture and start moving toward a “learn-and-improve” culture?

First, it had to be recognized that learning and punishment cannot work together; blaming silences people and fixes nothing. Then, it was decided to pick up learning as the main driver for safety and as the framework for the development of the safety culture program.

Human error is normal. Learning how the work is done is the best approach to help people work safely, rather than fixing things when something goes wrong. Such concepts synthesize the “new view of human factors.”

Many leaders in the oil and gas industry still see human factors as a mysterious and abstract concept, too academic to be translated into practical tools that can be applied in day-to-day operations. To get leadership onboard with these new paradigms, the initial stages of the safety culture program focused its main goals on reinforcing management awareness. It was crucial to get their understanding and engagement and to work with the front-line staff to build an environment based on trust and accountability to safety.

Therefore, biweekly safety meetings chaired by the JPT director (Petrobras executive manager) with Seadrill’s VP Brazil and their staff were established to share expectations and define common goals on a collaborative approach to safety. The main goals were to have an increasingly transparent flow of information among the stakeholders and the construction of an environment based on mutual trust and collaboration, coupled with accountability.

Likewise, weekly safety meetings at the operational level helped to translate those abstract concepts into practical actions on the front line. Operational performance was never discussed in these meetings, since the belief was that focusing on the “learn-and-improve” approach would bring both safety and operational excellence. The objective was to de-emphasize the “old view” to safety, materialized with the massive adoption of safe behavior programs across the industry, and promote an open discussion about different safety approaches, mainly with the introduction of the paradigms proposed by the “new view.”

One of the first steps toward such translation focused on Petrobras’ own supervisors, the company representatives working onboard the rigs. All of them took part in training sessions to increase their awareness of safety and the importance of becoming the messengers – the real protagonists in this long process of transition to a more collaborative environment.

These representatives started, for instance, to actively take part in most of the daily planning meetings carried out by Seadrill’s supervisors. For this, it was critical for Seadrill to demonstrate an understanding of the purpose of the safety culture program, in order to keep the doors fully open to our representatives. Furthermore, every single worker, upon arrival on the rigs, was to be formally received in the arrival briefing by the Petrobras company representative and the OIM to demonstrate the integration and explain common expectations and how everyone could contribute to improving safety.

Logically, to build trust and accountability, the language had to change. Rather than using a coercive manner to get things done, language should demonstrate cooperation, collaboration, shared objectives and respect through non-violent communication at all levels, from management to ground-floor workers.

In the meantime, human factors coaching was provided onboard the rigs, fully supported by both JPT and Seadrill leadership, to speed up the process. This involved walkarounds to interact with people at their worksite; individual and group discussions; training sessions; and lectures to enhance non-technical skills (e.g., hazards identification, risk management, job planning, teamwork, learning teams, human error and systems view).

It was interesting that most of the tools that were used to improve safety onboard the rigs were actually already there at everybody’s disposal – although dormant. The supervisors and crew simply needed guidance to start trusting those tools and see the real value behind them.

As an example, Seadrill makes use of observation cards, like most drilling contractors do, to get people involved in safety. Initially, observation cards were filled in merely as compliance with management requirements. Observations were weak, and proposed solutions for hazard findings were only focused on correcting human behavior as expected.

After coaching and other initiatives, many cards started to show a much broader systems view. Improvements in equipment and tools, design modifications, elimination of non-practical tasks and simplification of procedures are just a few examples of solutions that popped up in the cards.

Another essential tool adopted by Seadrill is what they call PIMED (plan the job, identify the hazards, manage the risks, execute as planned, and debrief for learning). PIMED would work as a fantastic tool to improve safety if workers knew how to plan appropriately, identify hazards, manage the risks, and so on. In this regard, assistance was given to help front-line workers and supervisors to improve their ability to make PIMED a more robust tool.

In parallel, the JPT celebrated an agreement with one of the most renowned private universities in Brazil, the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS) for the development of a research project in human factors and resilience engineering in deepwater operations. PUCRS encompasses a school of aviation, the industrial segment that pioneered the adoption of human factors to improve performance.

This research project has been fundamental in helping the team to learn from other industries, such as commercial aviation. Important lessons included the application of human factors and systems thinking and how their best practices and human factors tools could be adopted into the process of deepwater drilling.

A multidisciplinary team of researchers was assembled and started their work in the first half of 2017 for an initial phase of two years. The researcher had the opportunity to interact with front-line workers onboard the rigs. Several exercises, such as storytelling, were conducted to include middle managers and supervisors (e.g., OIM, drilling superintendents and Petrobras companymen). The objective of the journey was to learn how to close the gaps between the work as imagined and the way the work is actually done.

As a result, in well construction operations, managers and supervisors of both the Petrobras project team and Seadrill became visibly engaged with the project. Most of the staff realized the importance of their contributions to create and maintain a much safer work environment.

It is worth noting the astonishment of anyone getting onboard the two rigs. They could feel the difference. Petrobras, Seadrill and, more critically, the front-line workers were able to collaborate and redesign the working system and empirically demonstrate the best way to reduce errors.

Instead of controlling people to change their behavior, a new context was created to drive people’s behavior onboard the rigs. They felt free and more confident to navigate within the complexity of the environment of their work. Not coincidentally, most of the solutions and improvements were created and developed by the very people working onboard the rigs.

Both rigs started to move upwards in Petrobras’ performance ranking. It took almost four years of hard work, but both rigs left the last positions and reached the top quartile to become part of the best in class among the Petrobras fleet, both in safety and operational performance.

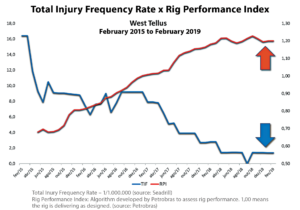

Figure 1 shows the results from the West Tellus after four years, with clear evidence that improvement in safety and operational performance can come together in harmony.

After this successful experience, Petrobras has expanded the work to include all major contractors joining the project, field service contractors and other drilling contractors. For instance, a comprehensive two-day workshop about human factors was developed in conjunction with PUCRS for the leadership, mainly top managers, to enhance their awareness of the new view of human factors and how its concepts and tools can be incorporated to the way safety is approached.

Establishing a cross-company collaborative environment helped the development of programs to stimulate deepwater drilling organizations. It helped them to recognize their inherent complexity and understand why safety must be approached differently in highly complex socio-technical systems to better cope with the sophisticated technologies and processes in drilling operations. DC