Indirect costs of incidents, fatalities make the financial case for better safety practices

By Joanne Liou, editorial coordinator

An investment in time, effort and money goes a long way to prevent injuries and to protect the work force, while saving millions of dollars and building a positive public image of the industry. “Safety is good business,” Warren Hubler, VP for HSE &T, Helmerich & Payne International Drilling Co, stated at the IADC HSE&T Conference & Exhibition on 7 February in Houston. “The significance is not in the direct costs; the significance is in the indirect costs that many companies do not realize.”

Direct costs of an incident include medical services, treatment, insurance premiums and deductibles, lost wages and OSHA fines. Indirect costs include time spent finding replacement personnel, hiring and training replacements, loss of productivity while shorthanded, downtime, etc. Mr Hubler compared the breakdown of costs to an iceberg. “The top part of the iceberg represents the direct cost that you see associated with the injuries in your workplace,” he said. “What many companies do not see are the indirect costs. It is the bottom part of this iceberg that is a hazard to future business and for you to remain a competitor.”

Building on evidence provided by five case studies ranging from small to large drilling contractors, Mr Hubler presented real-life examples to calculate the direct cost and indirect cost, which was conservatively estimated to be five times greater than the direct cost.

In the first study of an OSHA-recordable finger laceration, the medical treatment would cost $6,500 if the worker is released to resume normal duties. However, if the incident results in a restrictive-duty case, it would cost $25,000, making the average direct cost of either medical treatment or restrictive-duty case $12,500, Mr Hubler explained. “If we used the indirect cost, at five times that amount, there’s another $62,500, and the total cost for that one event is $75,000 to the employer,” he said. According to IADC’s Incident Statistics Program, four OSHA-recordable injuries occur every day in US land and offshore operations. “Our industry as a group, as a whole, is (wasting) away $300,000 every day just to cover the costs of our mistakes,” he added.

Another way to demonstrate the significance of the total cost of an injury is to consider that the cost of one OSHA medical treatment or restrictive-duty case is equivalent to three days of lost revenue, and one LTI is equivalent to 48 days of lost revenue. “Every operations manager and drilling superintendent will jump through hoops to prevent just three consecutive days of downtime. If we won’t tolerate three days of downtime because of its financial impact on our business, why do we accept OSHA injuries as simply the cost of doing business?” Mr Hubler asked.

Further, to emphasize the business impact of an incident, Mr Hubler analyzed the cost of a parted drill line without any personal injury or fatalities around the rotary table as a result of being crushed on the blocks. The direct cost, which includes the new service loop, new drill line, lost revenue and rental equipment, totals $650,000. The indirect cost would then be $3.25 million, for a total cost of $3.9 million. In an up market, the rig would not be making any contribution to the company’s bottomline profits for the next year. “How many rigs can you operate in your operation at zero margin and still remain a competitive, profitable business?” he asked.

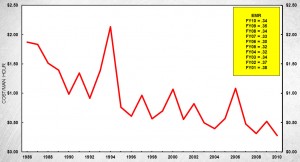

The direct and indirect monetary effects of an incident can be calculated and covered, but the human effects are invaluable. Based on 2003 to 2009 data from the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health, the oil and gas industry has one of the highest fatality rates in the US. For every 100,000 workers, there are 27 deaths versus an average of four fatalities for all other industries.

Mr Hubler emphasized that the direct and indirect costs of an incident can be covered, but not so for the ultimate loss of a life. “It is the employers who find a way to cover the direct and indirect costs of deaths, but our families, their families, do not,” Mr Hubler said. “The ultimate price for workplace injury or fatality isn’t paid by the employer; it’s paid by the employee and his or her family.”

The full article in the January/February 2012 issue of Drilling Contractor features details on the five case studies: large contractor with a high insurance deductible; lost-time injury for small drilling contractor results in zero profit for one month; mismanagement of injuries may cause injury costs to skyrocket; financial impact of a fatality on the worker’s family; and safety is personal – beyond dollars and cents, there is a human cost.