How to learn from our past: Debunking 6 myths of process safety

Asking the right questions will bring new perspective on process safety, create new solutions

By Vivek Bhatnagar, Phillip Townsend Associates

“The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the level we were when we created them,” said Albert Einstein. And yet, we continue to do the same things over and over again, expecting different results.

Are we missing something? Why is it that despite several major oil and gas industry disasters, we continue to repeat the same fundamental mistakes? You may argue that each disaster is different and, therefore, cannot be compared, and you would be right.

However, if we look at the investigation reports more carefully, peeling away layers of individual actions, there are striking similarities at a fundamental level: the focus on slips, trips, and falls as opposed to major catastrophes; absence of policies and procedures with regard to critical high-hazard activities; failure in learning from others; a system of rewards that promotes and recognizes high-frequency, low-consequence events but mostly sits silent on low-frequency, high-consequence events; absence of procedures that automatically escalate a high-risk situation to more experienced and competent people when things deviate from their planned path; silo’ed systems with absence of cross-functional integration and communication; an organizational culture that fosters and even forces budgetary and schedule imperatives to take precedence, exposing the rig to much higher but not necessarily fully understood risks; and finally, a huge perception gap between senior leadership’s stated vision and their information regarding what’s actually happening on the rig floor.

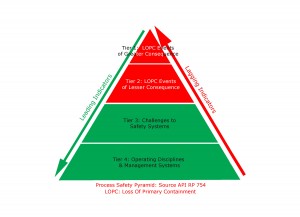

All of these causes basically relate to operating disciplines and management systems and therefore – given its broad definition – classify under process safety. Figure 1 explains the different tiers (or grades) of process safety as published in API RP 754.

Have we failed to learn from our past?

If we have, it is attributable to these three reasons: Process safety is 1) hard to understand, 2) difficult to measure and 3) tough to manage.

In the absence of a better understanding, with every new disaster, we take recourse to doing more of what we were good at: focused harder on personnel safety, bringing down our LTIRs and TRIRs even further; strengthened our policing, increasing the number of our HSE personnel and policies and instituting stricter penalties for violators; improved our compliance; and in general have done everything we thought would help while continuing to remain at the same level where the problem lounged.

Not surprisingly, our results haven’t changed much. Remember, if you do what you’ve always done, you’ll continue to get what you’ve always gotten.

Time for new perspective

The time has come to see the world differently, and this starts with our understanding of the very concept of process safety.

The International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (OGP) defines process safety as “a disciplined framework for managing the integrity of operating systems and processes that handle hazardous substances. It is achieved by applying good design principles, engineering, operating and maintenance practices. It deals with prevention and control of events that have the potential to release hazardous materials and energy.”

Since this involves actions starting as early as the design phase and continues all the way to actual drilling operations, it covers a whole range of activities. Any human behavior, equipment failure or process gone awry that eventually contributes to a blowout is therefore included under this definition.

Since we routinely deal with hazardous substances under tremendously high pressures, use ever more sophisticated machines, follow intricately complex processes and utilize a myriad of focused competencies in people, process safety is how we do our very business.

But hasn’t this been the way since the time we started drilling? What has changed now?

It’s semantics

Over the ages we have called process safety by different names, starting with the generic “cost of doing business” and “standard operating procedures,” moving on to the more narrowly focused “asset integrity,” then flirting with “operations integrity” and now to “process safety” – a term we had heard before but never really cared about since it didn’t apply to us.

How come things have changed suddenly?

There has been one change other than the semantics, and that has had a far more profound impact on our business than we have cared to acknowledge.

In the old world where things were less complicated, we could get away with more blunders and taking far more risks using much simpler processes.

Not anymore.

As we move deeper and farther offshore, we encounter challenges not faced earlier. Yet, in many regards, we have continued with a “fly-by-the-seat-of-our-pants” way of doing business. This has resulted in situations with far worse fallouts than previously conceived or experienced. In cases where we have not been able to control them, results have been catastrophic.

While the world around us changed, we continued with our existing perceptions that were grounded more on tradition than on the new reality surrounding us.

Since in the past our major concern was more related to personnel injuries, we generally equated safety with slips, trips and falls.

The same pioneering and adventurous spirit that “got the job done” in the past turned our boon into a bane.

However, it must be acknowledged, given the spate of high-consequence incidents in the recent past, there has been renewed interest in the subject. We have made progress in better understanding, albeit it’s more about our lack of knowledge of the same than anything else.

And that has made us realize there are several challenges that lie ahead. Unless we find a way to deal with them, we will continue to struggle.

Now what?

The biggest challenge in solving any problem involves separating truth from falsehood. This requires knowing what is real and what isn’t. While this may sound simple, it is not.

Notwithstanding, we have to start somewhere. One reason process safety, despite its ubiquity elsewhere, is hard to understand is that it comes with a lot of baggage. Separating those myths from realities is a good start.

The six process safety myths

Six myths surrounding the concept of process safety as they apply to the offshore drilling industry have prevented us from achieving a better understanding of the subject.

Myth 1: Process safety applies to steady state operations typical of the downstream chemical industry

While the concept of process safety was more popularly espoused by the downstream chemical industry to better manage their steady state and largely predictable operations, if we read the definition of process safety carefully, we see that it has more to do with managing integrity of operating systems and processes dealing with hazardous substances – something we do on a routine basis – than with being steady state or predictable.

We can’t say that process safety doesn’t apply just because our operations are more dynamic. We still rely on laid down and systemic processes and procedures to deal with rapidly changing and unpredictable operations.

Once we internalize the idea that our actions, however small, contribute toward making operations inherently safer or otherwise, we are better positioned to effectively apply process safety. Things that earlier we were either ignoring or not even noticing, we would now be able to see them as potentially undermining process safety. A simple example would be deliberate bypassing of alarm systems. Rather than finding a way to improve our alarm system, it is not uncommon to find a way to bypass it because of its sheer nuisance value. While one can get away with it a majority of times, when things are going wrong, this practice could prove disastrous.

Myth 2: We can measure process safety

This is only partially true.

What we measure and call process safety is different from what we have been focusing on so far. We do have metrics to measure process safety incidents, but that’s after the fact. There’s little we can do about it. The process safety we are interested in is about things we can do something about. We are interested in the leading indicators that tell us where we are headed instead of lagging indicators that tell us where we have been.

And that is something that you cannot measure. This is because, by its very definition, process safety involves almost every aspect of our business. To measure process safety would be to measure everything. While possible, that is a herculean task. Worse still, we don’t even know what relation a particular metric has with the possibility of a disastrous event. This causal relationship is not apparent.

While past incidents do provide a valuable treasure trove in the form of insights and lessons that can help avoid repeating the same mistakes, there is one huge challenge.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, studying a major incident investigation report tells us the aspects of the operating disciplines and management system that were responsible for that particular disaster. We can take corrective actions to prevent a similar mistake happening again as part of our follow-up learning. But the next disaster may not follow the same course. It may involve other operating disciplines and management system aspects that may be the same at the fundamental level but differ significantly at an implementation level; and to know which ones in advance is nearly impossible. It’s only in hindsight that we have such great vision.

While waiting for another disaster to give us a new list of things to avoid might seem a logical step, it is too costly and inefficient way to learn.

The better way, therefore, might actually involve measuring everything, however big or small, and then using the power of data analytics to look for correlations that may be invisible to the human eye. In this, the larger the data pool, the better the chances of success.

Myth 3: Our current safety performance metrics are good indicators of our (process) safety performance

Nothing is farther from truth than this, and nothing exemplifies it better than Macondo, where one of the biggest offshore industry disasters in US waters happened on a rig that was being recognized for its exemplary safety performance.

We have judged our overall safety performance using the wrong tools, facing the wrong direction and measuring the wrong things. It’s like driving with our windscreen completely blacked out and using only the rear view mirror. Just because we have driven a couple of miles without running over someone does not mean we are not about to do so or drive over the edge of a cliff the very next minute.

We need to look again at the kinds of metrics we are relying upon to ensure we have a much better idea of where we are headed instead of knowing where we have been.

Myth 4: Other companies’ process safety problems are not my problems

We falsely believe that so long as I take care of my process safety problems, I am fine. Unfortunately, that is not the case.

Every major past incident has resulted in new regulatory focus that has hurt not just those accountable for it but also everyone else within the same industry. Therefore, even if one company is not being responsive to ensure it has proper process safety practices, the impact is going to be felt by everyone else. This means your process safety problem is not just yours. It’s mine as well.

This concept goes against the current popular industry thinking where companies compete for the same clients by trying to provide services that distinguish them from their competitors.

Process safety requires a collaborative industrywide sharing of information and a concern for each other’s well being. Unfortunately, at the operating discipline and management system level, there is minimal collaboration happening as of now. This needs to change, if the industry wants to do a better job of its process safety performance.

Myth 5: We can solve process safety issues by better policing

Throwing more money or people with greater power is treating the symptoms while allowing the disease to continue unabated. Adding another layer in an organization with more authority and policing power can provide short-term gains but could ultimately lead to a bigger problem – a false sense of well being, that everything is going well and we have things under control.

A better approach would be to see how each individual in a company is empowered enough to take personal responsibility for doing what is right for the rig. It involves identifying and removing any possible obstructions or management policies that lead to people gaming the system to attain short-term rewards.

It is not about adding layers but removing obstructions. Unfortunately, this is a lesson not easily understood and rarely followed.

Myth 6: Process safety is an HSE function

Going back to the process safety definition, we see that it’s about the way we do our business and not about safety. In fact, the definition doesn’t even include a reference to the word “safety.” It talks about design, engineering, operations, and maintenance – functions at the very core of our business activities, which means it is the responsibility of everyone in the company and not just a particular individual or department.

Therefore, placing process safety under a department such as HSE sends out wrong signals. It gives an indication that process safety is no more my problem; it’s the HSE guy’s.

Additionally, if there are conflicts between the design, engineering, operations and the maintenance people, e.g. when scheduled maintenance collides with operational exigencies – something that is not too uncommon – who do you think is better positioned to resolve the issue? The HSE person?

It has to be a person with the executive authority, a person who can see all these functions with an equal and dispassionate perspective and has the authority to tell one or more of the conflicting representatives to shut down, if and when needed.

I would argue process safety needs to be owned by the very top leadership. Only then is it possible to send out the message that we care enough about how we do our business and that shortcuts will not be tolerated.

Finally, I believe, there is no problem in the world that cannot be solved. So, how come we still continue to struggle with the same problems? Because we are not asking the right questions.

Ask and you shall receive

Instead of asking “Can I get away with this?” ask “Is this 100% safe?” Instead of asking “How soon can I get this job done?” ask “Is my decision to speed things up based upon sound operational policies or is it guided by budgetary and scheduling constraints?” Instead of asking “Are we doing it this way because we have always done it in this manner in the past?” ask “By taking this course of action, am I ensuring 100% safety for all even if we haven’t had an incident in the past?” Finally, instead of asking “How do I reward my people to promote zero incidents?” ask “Is my management system of rewards and recognition doing what it’s supposed to do or is it promoting unintended consequences motivating people to game the system?”

Once we ask the right questions, we will get the right answers. Until then, we will remain at the same level where we were when we created our problems.

This article is based on a presentation at the IADC Drilling HSE Europe Conference & Exhibition, 26-27 September, Amsterdam.

Vivek has an ability to make what appears to be a high-level, complicated subject make sense to those of us involved with field operations whether drilling or production related. Field HSE representatives can be very beneficial to operations in the area of process safety primarily because of their outlook. They can only be so if they are allowed to participate in all phases of the processes including design, installation and maintenance/operation. When there is a line drawn between HSE and the other functions, management is failing to utilize an important tool. Even if HSE functions only to questions regarding risk, they can provide important insight.