Full-scale test well study reveals insights into gas migration, shut-in pressures in water, SBM

Shut-in riser pressures from gas influx found to be lower than expected, disproving idea that gas migrates as single bubble from bottom

By Mahendra Kunju and Mauricio Almeida, Louisiana State University

Historically, when there is a gas-in-riser event, well control guidelines have prioritized managing the riser gas first to prevent gas from reaching the surface, thereby safeguarding personnel and assets. However, once the riser is isolated from the wellbore by a closed subsea blowout preventer (BOP), no additional energy is introduced into the riser, and maintaining constant bottomhole pressure during riser gas handling becomes unnecessary. Securing the wellbore with the closed subsea BOP expands the operational window for allowable flow rates and pressures. Consequently, the greater risk shifts to the wellbore below the subsea BOP.

With the advent of adaptive drilling techniques such as managed pressure drilling (MPD), which enables safer, more efficient drilling and rapid response, the industry must reassess and modernize traditional well control practices accordingly.

This article presents results from full-scale experiments conducted in Louisiana State University’s Well-2 using water and synthetic-based mud (SBM). It demonstrates that riser pressures caused by the upward migration of riser gas are significantly lower than pressure values typically estimated in the industry.

The research consists of two main parts. The first investigates gas influx in a well annulus (riser) using water and nitrogen – fluids with low compressibility, viscosity, surface tension, yield stress and minimal gas solubility – to simulate a worst-case scenario of high shut-in pressure. The second explores gas behavior with nitrogen in SBM, which exhibits yield stress, viscosity, surface tension and greater gas solubility and compressibility, enabling examination of gas absorption and desorption.

Both sets of experiments were conducted in the same well, with water and SBM having very similar densities. Beginning with the simpler water-nitrogen system establishes a controlled baseline while the SBM-nitrogen tests incorporate realistic drilling mud properties, providing key insights into gas migration and helping to address industry concerns about gas management in risers.

Figure 1 shows a well sketch of the full-scale vertical research well (LSU Well-2).

Four experiments (W02, W06, W11 and W13) were conducted in a water-filled well to investigate gas-in-riser behavior and quantify pressure changes and the maximum shut-in pressure at the surface. Before each test, the well was circulated and conditioned, then allowed to remain stagnant until static pressure and temperature readings stabilized. Prior to gas influx, pressures measured by the deepest gauge (D) ranged from 2183 to 2188 psi, and temperatures ranged between 104°F and 106°F.

Four experiments (M03, M04, M05 and M06) were conducted in an SBM-filled well to quantify the potential for gas migration to generate high surface pressures under shut-in conditions. This knowledge, along with the gas-handling capacity of the rig, can be useful in evaluating the different gas-handling options based on the associated risks.

Prior to gas influx, pressures measured by the deepest gauge (D) ranged from 2187 to 2196 psi, and temperatures ranged between 100°F and 105°F.

Figure 2 shows the quantified maximum values of final stabilized surface shut-in annulus pressure vs elapsed time for different gas influx volumes in water and SBM.

As the gas front entered the SBM-filled annulus, gas began to dissolve into the mud. The dissolution was not instantaneous. However, it reduced the gas volume in the annulus, causing a drop in the SBM liquid level. Due to U-tubing effects, the liquid level in the tubing also decreased correspondingly. These changes are visible in the plot on the right of Figure 2, where the dashed green line disappears between 8 and 65 minutes, and the dashed yellow line vanishes between 12 and 38 minutes. In contrast, gas dissolution was negligible in the water-filled annulus.

The test results reveal that, contrary to common belief, maximum shut-in pressures due to gas migration in a shut-in annulus are much lower than expected, even in the worst-case scenario using water and nitrogen. Many earlier models treated the gas as a single bubble in a rigid well system. Under this assumption, bottomhole pressure would be expected to reach the surface as the gas migrates upward. However, the observed maximum shut-in pressures are significantly lower than those predicted by field thumb rules or Boyle’s law.

Furthermore, comparing gas influx volumes in water versus SBM shows markedly different behavior, with shut-in pressures substantially reduced in SBM, demonstrating the impact of non-aqueous drilling fluid properties on pressure magnitude.

Factors affecting shut-in pressure

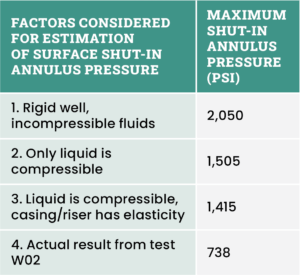

It is crucial to isolate and quantify the individual factors contributing to shut-in pressures being lower than typically expected. Four distinct cases were identified, with their estimated surface pressures presented in Table 1. These calculations consider a 5-bbl nitrogen gas influx migrating from the bottom of a water-filled riser annulus under shut-in conditions.

The first case assumes gas migrates as a single bubble and uses calculated temperature and z-factor, predicting a shut-in pressure lower than the value expected by Boyle’s law. The second case adds liquid compressibility, accounting for volume increase as the liquid compresses. The third includes casing/riser elasticity, adding volume from casing expansion. While these three cases improve pressure estimates over simple Boyle’s law assumptions, they still don’t fully explain the lower shut-in pressures observed in actual tests. The fourth case presents the actual test results. Modeling maximum shut-in annulus pressure for LSU Well-2 across these scenarios highlights how estimated pressures can differ significantly from real measurements and often fall below values predicted by traditional field rules.

Because of the large volume of the long, wide riser used on the rigs, system compressibility significantly affects riser pressure and cannot be ignored. To quantify this, two tests were conducted to estimate the system compressibility of LSU Well-2 when filled with water and two additional tests when filled with SBM.

The total injected liquid volume equals the sum of the three component volumes below, assuming no trapped gas in the system.

Volume injected = Reduction in volume due to liquid compression + Volume gained due to expansion of riser (casing) + Reduction in volume due to compression of volume added to fill the additional space created. The average system compressibility measured for Well-2 was 3.7 × 10-6 psi-1 with water and 4.65 × 10-6 psi-1 with SBM.

Data analysis methodology

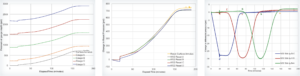

Only the pressure recorded by the downhole and surface gauges are used for the data analysis. All four downhole gauges and the surface annulus gauge show a similar trend of pressure increases due to gas migration, as can be seen on the left side of Figure 3. Because the research is interested in the change in pressure as the gas migrates, a plot of change in pressure at each gauge is shown on the middle plot of Figure 3. The actual pressure at each gauge was corrected by subtracting the stabilized pressure of the stagnant liquid column above it before the test began. To get a better understanding of what is happening to gas, a plot of the difference in the reset pressure values between adjacent pairs of gauges is shown as a differential pressure plot on the right of Figure 3.

The zero time is when the gas front entered the annulus at gauge D and capital letters C, and B shows the elapsed time when the gas front reached gauges C, and B. The small letters d, c, b and a show the elapsed time when the gas tail reached gauges D, C, B and A. These figures demonstrate the possibility of using the methodology for the detection of gas and location of gas in an annulus.

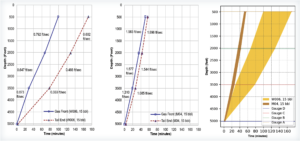

Gas rise velocity

The gas cloud migrates up with a gas front velocity or lead velocity and a tail velocity. The elapsed time when the gas front and tail end reached each of the gauge depths (gauges D, C, B, A) for the 15-bbl gas influx tests in water and SBM is shown as plots on the left and middle of Figure 4. The elapsed time was estimated using the location of gas shown on the differential pressure plot on the right of Figure 3. A comparison of the length and dispersion of gas columns as the gas migrated up in the annulus is shown on the right of Figure 4.

The average gas front and tail velocity between gauges is determined as the slope of the line between the gauge depths. Though both the lead velocity and tail velocity reduced as the gas cloud migrated up, the tail velocity reduced at a faster rate in water. This caused the gas cloud to stretch increasingly during migration. The greater the length of the gas cloud, the lower the gas fraction for a unit length of the annulus. The diverging trend of the gas front and tail end for W06 can be seen in Figure 4. Migration in SBM was finished in a third of the time it took for the same volume to migrate in water.

Conclusions

- Full-scale experiments revealed that shut-in riser pressures from gas influx were much lower than commonly expected, disproving the idea that gas migrates as a single bubble from bottom to surface.

- Lower observed pressures were mainly due to gas dispersion, gas column stretching, liquid compressibility and annular elasticity, even with low-solubility nitrogen migrating through water.

- Bubble fragmentation significantly reduced the gas migration velocity in water, as the swarm of bubbles traveled much slower than the gas front, leading to stretching of the gas column.

- Gas bubble dispersion and stretching of the gas column were not noticeable in SBM tests, as the rheological properties of SBM helped maintain bubble cohesion compared with water.

- The gas front and tail were more sharply defined in SBM due to possible dissolution of any bubble fragmentation and dispersion that may have occurred at the boundaries of the gas column.

- Higher nitrogen dissolution in SBM compared with water was the main reason for significantly lower shut-in pressures in SBM.

- Accurate maximum shut-in pressure estimates require realistic system compressibility values, so compressibility tests are strongly recommended when introducing new mud.

- The method developed to calculate differential pressure changes from downhole gauges effectively detects gas presence and location in the riser.

- To improve well control and avoid overestimating riser pressure in gas-in-riser situations, future methods must include gas solubility, dispersion, bubble suspension, fluid compressibility and riser ballooning. This will enable more accurate risk assessment and better well control strategies for offshore drilling. DC

This article is based on a presentation at the 2025 IADC Well Control Conference of the Americas, 19-20 August, New Orleans, La.