Industry takes cautious but sure-footed steps toward hands-free drilling, automation

by Linda Hsieh, Assistant Managing Editor

When it comes to risk-taking, this industry seems to suffer from a case of multiple personality disorder. On the one hand, it has a tendency to be big gamblers. It’s willing to spend millions or tens of millions of dollars – maybe hundreds of millions or more, if you’re talking deepwater – drilling exploration wells that have unknown chances of success. The industry understands that although the risks may be high, the rewards that could be gained are even higher.

When it comes to automation technologies, however, that philosophy sometimes gets overlooked. The risk-taking optimist gets pushed to the back, and out comes the cynical conservative who eyes “machines” and “computers” with mistrust. “Will it really improve the drilling operation?” “Will it cost me NPT with failures and extra maintenance and repair time?” “Will it require additional training for my crews?” “Will the benefits outweigh the costs and risks?”

Historically, the drilling industry has been slow adopters of new technology, and steps that have been taken toward automation and mechanization have been hard-earned. In general, we don’t like to be the first to try anything new – we want The Other Guy to try it first and make sure it works.

Given the costly and complicated nature of oil and gas drilling, a cautious approach is entirely understandable. But as the industry inches along the path toward automation – and some companies say this path is inevitable – both drilling contractors and service companies point to the potential rewards that could be gained. They include better safety, increased efficiency, reduced risks and overall optimized drilling.

TECHNOLOGIES ON THE RIG

As a whole, today’s drilling rigs are far more technologically advanced than ever before. Through the widespread use of equipment like electronic drillers, PLC-based control systems, top drives, iron roughnecks, pipe-racking systems and mechanized catwalks, rigs nowadays no longer have to rely on manual control and mechanical systems, which are much less consistent, efficient and accurate.

“George Boyadjieff’s top drive set the stage for a lot of things in terms of automation,” said Alan Orr, executive vice president – engineering and development for Helmerich & Payne International Drilling Co (H&P). Such as providing the capability to back-ream while pulling out of the hole; this enables drilling today’s long horizontal sections and extended-reach wells.

Later, coupling the top drive with variable frequency drive AC power propelled the industry into a new era of control systems, bringing new levels of precision and repeatability to rigs. PLCs also emerged in the oilfield, allowing the integration of many mechanical devices on the rig floor and letting drillers and assistant drillers coordinate activities remotely from within climate-controlled driller’s cabins. Improved data telemetry techniques delivered to the drillers more downhole information, which was being acquired in larger amounts and in better quality with the use of technology such as wired drill pipe, logging while drilling, optimization algorithms and improved electronic sensors.

Mr Orr noted that with the introduction of the electronic driller on H&P’s FlexRigs, the land drilling industry took another step forward by using computers, software and touchscreen controls to monitor and adjust multiple parameters and to optimize drilling and reduce/eliminate problems that used to plague the industry.

For example, he continued, electronic drillers together with VFDs brought regenerative braking to the oilfield. That replaced mechanical brake systems and resulted in much more precision, steady-state control and less physical exertion for the driller.

Used in conjunction with real-time surface and downhole data, automated systems can set specific speeds for pulling in and out of hole to reduce the surge and swab issues that are sometimes associated with human errors. Currently, organizations have used surface data and modeled drilling systems to enforce such speed limits on a platform drilling in the North Sea. Wired drill pipe has been used to send downhole information to the surface at accelerated data rates. R&D efforts at several companies are under way to integrate surface and downhole data to add fidelity to drilling models and perhaps, in the near future, to provide closed-loop control on certain downhole operations.

And even for conventional rigs with early-generation braking systems, incremental improvements through retrofitted basic digital controls have been made possible, due to advances in signal processing and electronic controls.

Autodrillers continue to improve, and David Reid, vice president for E&P business and technology with National Oilwell Varco, said he believes the industry has gotten to a point where autodrillers are what the top drilling performers are using and are bringing benefits on a regular basis. “People are getting efficiencies up to 30% on any given well just by using autodrillers and optimizing the drilling process,” he said.

Today, an advanced autodriller can continuously and simultaneously monitor multiple drilling parameters – weight on bit, rate of penetration, torque and differential pressure (delta P) – in conjunction with sensors, computers and data acquisition systems. In a paper presented at the 2009 SPE/IADC Drilling Conference in Amsterdam, field results from the Barnett Shale over a seven-month period showed that wells drilled with an advanced autodriller increased rate of penetration by more than 30% and reduced the numbers of bits used by 7%, compared with wells drilled with a conventional autodriller.

EVOLUTIONARY PROGRESS

When asked if there have been revolutionary automation advances in the past few years, several service companies seemed to agree that there haven’t been dramatic new inventions. That isn’t to say there hasn’t been progress.

“In the last few years, the achievements have been to stabilize the technologies that have been available for the last 10 years – making them less susceptible to minor errors, easier human machine interface, improved fault-finding technology – because that’s been the main feedback from operators,” said Bjorn Rudshaug, vice president – research & development with Aker Solutions.

In fact, automation systems on the sixth-generation offshore rigs have “pretty much” the same functionality as the fifth-generation rigs – they just perform better, he said.

At Weatherford International, global product line manager – rig mechanization Egill Abrahamsen agreed. “It occurs to me that the drilling rig packages being delivered have been refined to a point where they are no longer revolutionary, the way some of them may have been looked at earlier,” he said.

There certainly have been incremental improvements though. Mr Abrahamsen pointed to V-tech, a Norway-based company acquired by Weatherford in 2008, and its development of the UniTong and UniSlip. The UniTong is a combination iron roughneck and casing tong able to handle casing, completion and drilling operations. Its thread compensation system can be used for connection and disconnection of all kinds of tubulars, and it has an integrated torque/turn computer and can be remotely operated from the driller’s cabin.

The UniSlip allows one set of slips to handle all tubulars in two intervals, from 2 3/8 in. to 10 ¾ in. and 9 5/8 in. to 16 in., to reduce the number of required change-outs on slips, especially for bottomhole assemblies in different sizes. There is also no need for changing inserts or slip segments during drilling or casing operations.

Control systems also have advanced, and one big step they’re taking now is having the ability to multi-task. Mr Reid of NOV cited the multi-machine controller his company provided for Maersk Drilling’s MÆRSK DEVELOPER semisubmersible. It is capable of letting one crew member control eight machines with one joystick, on top of normal controls. This means the human isn’t just telling the machine to perform single actions; he’s telling the machine to do a sequence of actions that can add up to an entire task.

On the MÆRSK DEVELOPER, the pipe setback has been moved to a separate level from the rig floor, and it’s the machines that are constantly working to bring pipe up to where they’re needed. “The guy who’s drilling is really getting pipe delivered to him. He just sets the rate at which he wants pipe to be delivered so he can use it to drill,” Mr Reid explained.

He added that while NOV has been doing this type of automated sequence controls for several years on different applications, the Maersk system has been their first true multi-machine controller. “We’re finally getting to the point where we think we’re doing it well,” he said.

DOWNHOLE AUTOMATION

Looking beyond the surface side and rig mechanization, one area that’s stirring excitement among drilling people is the automation of downhole activities and its integration with surface equipment. The interest was particularly evident at this year’s SPE/IADC Drilling Conference in Amsterdam, where the drilling automation session was one of the most highly attended sessions of the whole event.

“There was a huge turnout of people who were interested in automation. It wasn’t just curiosity; they were actually interested in doing it, and that hadn’t existed up to this point. The real forward-looking companies were there before, but the masses weren’t. So the numbers weren’t there to justify the assignment of resources to do a lot of these projects,” said Fred Florence, product champion at NOV.

“Now, I think the business conditions are changing. As people look for ways to ensure they get the well to bottom and drill within their cost target, they’re more open to using (automation technologies) for risk mitigation and cost reduction,” he continued.

Downhole measurements have also gotten better, allowing operators to see into the wellbore much more clearly than before. At the same time, breakthroughs like wired pipe are bringing data up to surface much faster and in larger quantities. “How can we put all this data to good use?” is the question many have been asking.

“The connection between downhole processes and topside automation is making large progress in terms of expert systems for drilling,” Aker’s Mr Rudshaug said.

“Like tight hole detection, automatic rate of penetration … where standard operations are integrated into the control system. … That’s currently being developed by several parties.”

For the past couple of years, Aker has been participating in the eControl project being undertaken with SINTEF, HPD and StatoilHydro to develop a system that will use wellbore visualization and drilling process models to optimize and control drilling. “We’re basically working on an automated drilling sequence where we integrate downhole measurements in an online decision support tool,” Mr Rudshaug explained.

This is a development that can be integrated with CADS (configurable automatic drilling sequence), a software tool involving sequencing automatic machine functions. “The control system will control the whole sequence. You can press a button for trip out, and the control system will do every step in that sequence for you. Previously, that required a lot of operator interface to start and stop the different machines,” he said. The CADS system was launched at the Valhall IP for BP in 2002. Since then, its functionality has been further developed and sold to other clients as well.

A similar but separate drilling automation project has been Drilltronics, where participants are trying to create a “drilling autopilot.” Like systems used to steer aircraft or ships without human guidance, Drilltronics hopes to ultimately be able to control drilling equipment using computer models for analysis of drilling processes. StatoilHydro, BP, ENI and NOV are participants in the project, which is based on the research and development of Norway’s IRIS.

NOV’s Mr Florence explained that a central focus of the project has been creating “envelope protection.” For aircraft, flight envelope protection refers to the control system that prevents the pilot from making control commands that would force the aircraft to exceed its structural and aerodynamic operating limits. Drilltronics is extending that same concept to drilling.

Participants are modeling drilling processes that can lead to automation or risk reduction, and Mr Florence said the bulk of the current work is on downhole pressures.

For example, a computer model has been created that can determine the maximum velocity at which the mud pump can run without damaging the formation at pump start-up. The computer can either notify the driller of the safe “envelope” to stay within, or actually control the equipment so that the driller can’t accidentally exceed the maximum speed without pushing an override button. Ideally, real-time downhole data will be used to continually update the model.

Field tests for Drilltronics were completed on the Statfjord C platform in the North Sea in 2008. According to IRIS, modules for tripping control, semi-automatic pump start-up and automatic friction test were applied during the drilling of the sidetrack 12 ¼-in. and 8 ½-in. sections. Drilltronics was applied during drilling in the reservoir without problems.

Currently, additional work is being done on the next phase of the model, Mr Florence said. “Once that’s done, they will schedule another field trial.”

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

A lot of innovative automation technologies are available on the market today, but perhaps what has kept them from really taking foothold is integration – a glue that will bind all the different pieces of the puzzle into a coherent picture. And although much work has been done to improve integration, much work remains to be finished.

NOV’s Mr Reid pointed to the large offshore rig-building cycle of the 1990s, when companies picked their favorite pieces of equipment from different vendors and put everything together into a complex machine. “But nobody really was sure who owned responsibility for the process,” he said.

In this newbuild cycle, it has become much more common for rig buyers to choose entire drilling packages – which means that process responsibility falls squarely on the suppliers to make the package of various equipment into an integrated and working machine.

Mr Reid said that NOV realizes the opportunities it has to advance integration for the entire industry, considering the company’s size and the variety of products under its roof. The company is pushing its internal groups to actively explore the potential for further integration.

“We’ve been able to see that the ability of all our equipment and systems to talk with one another is an opportunity for us,” Mr Reid said. “There’s an opportunity for us to look at the bigger picture and develop products that fit together. … We’re taking it quite seriously. We realize we have a responsibility as a community of suppliers rather than just individual people doing their thing.”

Drilling contractors are doing their part as well, making sure their rigs have all the supporting technologies and the right environment to help automation technologies perform as they were designed.

For example, Maersk Drilling has made significant investments in advanced technologies and equipment to make their fleet one of the world’s youngest and most sophisticated. Claus Hemmingsen, CEO of Maersk Drilling and partner & member of the Group Executive Board in A.P. Moller–Maersk, said his company has made “a profound effort in optimizing our fleet. … Offering dual pipe-handling systems, computerized drilling systems and fully mechanized tubular handling, our new-buildings are up to 20% more efficient compared to less automated rigs.”

“Very early on, we in Maersk Drilling acknowledged the huge potential in removing activities from the critical path and having parallel activities, thus reducing overall time to perform the operations. Introducing offline stand-building of casings has made it possible to increase rig performance and productivity due to allowing drill pipe stand-building operations to continue whilst drilling.”

The remote operation of the drill floor and the fully automated riser handling system also have resulted in almost no crew members being on the drill floor while drilling, which has led to safer operations, Mr Hemmingsen added.

In the land drilling market, H&P has no doubt been a preeminent leader in advanced-technology rigs. It was their use of variable frequency drives (VFDs) and AC motors throughout the drilling systems on the Flex 3 rigs that set the stage for land rig acceptance of AC power. That has led to a number of further advances for the company – like the H&P Flexhoist, a drawworks that takes advantage of variable frequency AC’s ability to have full torque at zero speed.

“You’re also able to get maximum horsepower over an expanded RPM range. With that, you obviate the need for a transmission in the drawworks, which makes it much more precise, reliable, lighter and with a smaller footprint,” said Mr Orr, chief engineer of the Flex3 rigs.

That’s in addition to the other advantages that come with VFD AC: programmable control, repeatability and precision.

H&P continues to make improvements to its FlexRig design by refining control systems to incorporate software routines that facilitate downlinking and other aspects of drilling optimization. They also expect to see incremental improvements in software, hardware and tubular handling, while further reductions in equipment weight and footprint will facilitate the industry’s move into areas like the Marcellus Shale.

The company will have close to 200 FlexRigs when its current newbuilding program wraps up in the first quarter of 2010. Noting the growing trend in horizontal and directional drilling on land, Mr Orr said there will be continued and increasing demand for technologically advanced rigs like H&P’s.

SIMPLE, NOT COMPLEX

As the land drilling industry moves toward higher degrees of automation, suppliers are figuring out how to make expensive and complex technologies work in a lower-cost environment. For example, systems that require software support personnel on the rig are probably not going to be practical for many land rigs. NOV’s Mr Reid said considerations like that are pushing companies to re-examine products and find way to make controls easier to use.

“It’s good because it forces us to look harder at the cost and to find ways to get simpler on the machines,” he said.

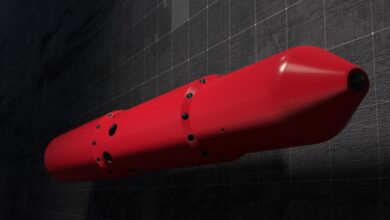

One example of this simplification may be the Iron Derrickman. A racking board-mounted pipe-handling system, this equipment was designed to be retrofitted on rigs – particularly land rigs – fairly easily. The system uses a robotic arm to lift and rack drill pipe and drill collars, eliminating the need for a derrickman on the monkeyboard.

Because the industry’s accident statistics have traditionally shown the derrickman to be one of the most dangerous positions on the rig, the Iron Derrickman offers clear safety benefits, said Jim Jones, business unit manager for Weatherford’s Iron Derrickman product group.

“When you combine tools like iron roughnecks, power slips and top drives, you get to a point where you can drill with most of the routine drilling operations controlled from inside the dog house from the driller’s station. There’s nobody out there in harm’s way, and that’s a good mission to be on,” Mr Jones said.

The company is also building a prototype of an iron floorhand that Mr Jones described as “a robotic arm that is anchored to the floor and controls the approach of the pipe as it swings from the v-door to the well center.” It is designed to complement casing running operations.

Mr Abrahamsen of Weatherford added that, in the last five years, top drive casing running tools have taken a foothold in the industry. “It’s really captured the interest of operating companies and service contractors,” he said.

For example, Weatherford’s Overdrive system combines several conventional casing-running tools into one – power tong, elevator, fill-up/circulation tool and weight compensator. This kind of remote-controlled system achieves hands-off casing running – an obvious safety advantage.

But there are drilling advantages as well. With this system, “you can circle, reciprocate and rotate the casing in the well, which enables you to ream through problem zones and to drill through problem – drilling with casing,” Mr Abrahamsen said.

“You would be able to get strings to bottom on wells that otherwise would have to be pulled out and re-run, or pulled out and recondition the well and re-run again. It’s a risk mitigator and an enabler for drilling engineers,” he continued.

THE HUMAN FACTOR

There are still many barriers that keep automation and/or mechanization from reaching its full potential in drilling operations, and one of the biggest may be ourselves.

During the 1990s build cycle, when many of the first deepwater rigs were built, much of the industry had a terrible experience with automation equipment, and that left a bitter taste in many people’s mouths, said NOV’s Mr Reid, who is chairman of the IADC Advanced Rig Technology Committee. “Every rig was custom-designed, and you ended up with a massive upturn in the amount of software that had to be written in a two-year period.”

Machines went out live on the rigs with barely any field experience and without being fully lab-tested to its extremes, resulting in significant downtime and maintenance difficulties. Instead of needing fewer people on rigs, as many assumed would happen, we ended up needing not only more people but more highly skilled people.

On top of that, machine efficiency often weren’t able to match the speed of manual crews.

“There was a sense of being cheated, that everything they’d hoped for in this new world of automation didn’t deliver,” Mr Reid recalled.

Of course, a lot of those troubles have gone away now. Technologies have matured, people have learned how to properly maintain and repair sophisticated equipment, and vendors have invested much more time and effort to test their products before commissioning. Techniques like hardware in the loop (HIL) testing are now used to test software with the actual hardware used for controls.

Aker Solutions conceived its HIL testing first as a training tool, but then realized it could also be a great tool for commissioning, Mr Rudshaug said. The equipment allows control systems to be run with a virtual model of the rig: “You use the actual control cubicles for the machines… You can virtually observe how the output of your control system is behaving.”

As a whole, the new offshore rigs being delivered in this cycle appear to be starting up without major hiccups. Maersk, for one, said their newbuilds have been launched with relatively few problems.

Since they consider the biggest risk with new equipment to be inexperience and lack of knowledge, they’ve minimized that risk by ensuring crews are well trained beforehand. Also, lessons that are learned on one rig are fed back to the next rig so there’s a constant loop of improvement.

“It’s a question of taking small and secure steps when introducing new technology and of remembering that introducing prototypes always comes with a risk of experiencing teething problems,” said Maersk’s Mr Hemmingsen, 2009 IADC chairman.

He added: “When launching our first ultra-harsh environment jackup MÆRSK INNOVATOR, we witnessed several issues with inexperienced staff that did not hold the required competencies. But as the crew obtained the necessary experience, the rig has now turned out to be one of the most effective in our fleet. When launching the sister rig MÆRSK INSPIRER, the knowledge among the crew of the MÆRSK INNOVATOR could be passed on to the new crew, thus building upon and utilizing the existing knowledge.”

Yet he cautioned: “But even with an experienced crew that has gone through the necessary training, it is important to constantly keep in mind and accept that with new technology, we cannot always do everything 100% right the first time.”

SAFETY VS EFFICIENCY

In deepwater operations like the Gulf of Mexico, mechanization is often not an option anymore; it’s a requirement. Put another way, it wouldn’t even be possible to drill these ultra-deepwater wells with the heavy, long drillstrings that are required without mechanized equipment.

But what about other places where humans can get the job done – maybe even faster than machines?

One of the biggest arguments in favor of mechanization or automation is safety. If you remove humans from hazardous areas like the rig floor or monkeyboard, the chances of injuries and fatalities are greatly reduced. However, sometimes safety alone may not be enough of a driver.

“The efficiency factor always comes in. You have to be providing some value as well,” Mr Reid said. “Safety is something you can train; you can change behaviors and how you work on a rig. It’s a necessity whether you have a machine or not.”

He added that although machine performance has improved with time, it’s not been enough to overcome the efficiency factor. “If you can match manual with a system, you’ll see a lot more people buying into the products. But if you’re lagging behind manual, then you’d better have something else to offer.”

Case in point: the Iron Derrickman. As a standalone tool, it is no faster than a man. A well-trained human could do the simple functions of the Iron Derrickman very well, said Mr Jones. But unlike humans, the machine doesn’t get tired and doesn’t need breaks. It will do its job consistently and repeatedly come rain or shine, hot or cold.

“But consistency and repeatability are hard to quantify in terms of improving productivity,” he said. Weatherford has been working on adding vertical and horizontal offline stand-building capabilities to the Iron Derrickman in order to give drilling contractors the “measurable” improvement they’re looking for. He anticipates these new features will be available by mid-2010.

H&P’s Mr Orr stated, “Delivering a measurable value proposition is essential when drilling contractors decide to invest in new technologies. Technology must provide value for our customers.”

THE CUSTOMERS TOO

Oil companies also have to see the benefit to their bottom line if any technology is really to gain widespread use.

“Introducing the new technology with a fully automated drill floor obviously facilitates a safer working environment … but performing in a more efficient way requires a crew capable of exploiting the new technology,” said Mr Hemmingsen of Maersk.

“Thus, training the crew, making them capable of utilizing the equipment to its fullest and thereby convincing the customers of their superiority is the foremost challenge to overcome.”

“If the oil companies are reluctant to take this new technology into consideration, then we might actually see a drop back in the level of technologically advanced rigs in the future.”

Mr Hemmingsen suggested that the success at Maersk Drilling has been predicated on creating partnerships with operators, and that should be the model for future successes as well: “Listening to their expectations and developing the new technology as a joint effort offers the best results.”

REMOTE OPERATIONS

Looking to the future, Mr Reid noted the importance of emerging technologies like wired pipe and single-board computers (SBCs), an alternative to PLCs already being used on some land rigs with success. He also believes that the industry will really start to explore the possibilities of remote rig operation. If rig floor equipment can be controlled from the driller’s cabin, theoretically they can also be controlled from hundreds or thousands of miles away.

That theory actually was proven out back in 2004, when NOV M/D Totco and Schlumberger successfully drilled a test rig in Cameron, Texas, via commands sent from Cambridge, UK. A remote-linking automated control technology, DrillLink, was used to transmit remote signals to the rig’s control system.

“That was the beginning of a larger wedge of being able to remotely control systems,” Mr Reid said.

This linking technology has been used in places like the Gulf of Mexico and Mexico for remote communications to downhole rotary steerable tools used to control the trajectories of directional wells. Moreover, this has been done on rigs with conventional control systems through the addition of an SBC controller. Use of this technique is growing, although the amount of engineering that is required for each rig has been a challenge. Mr Florence said, “There are thousands of rigs with thousands of controls, and they’re all different. Engineering interfaces on all these control systems has been the slowest part of the industry uptake.”

MAN-LESS RIGS?

Automation and remote operation all seem to open up great potential opportunities for the future, but looking at all the effort the industry is putting into these technologies, are we really trying to get to the totally autonomous rig that works on its own? Is that possible and would we even want it?

First of all, experts say we’re nowhere near being able to have an autonomous rig. Mr Rudshaug pointed out that one key element is still missing: standardization, both downhole and on surface, which would allow vendors to standardize all operations. “At the moment there is no drive in the industry to standardize the various dimensions and handling philosophy of various bits and pieces,” he said, adding that there’s also “no dominating player that can introduce the Microsoft Windows for drilling.”

Second, is the goal of automation really to have fewer (or no) people on the rigs? Not really, according to Mr Reid. Machines are only good for some tasks – primarily repetitive tasks and those that require a level of precision or complexity that humans aren’t capable of. So when machines take over these tasks, it’s not so that we can send fewer people out to the rig site. “The goal is to make these repetitive tasks simpler so crews can focus on the more complex variables on the rig, for which humans are best suited,” he said.

In some cases, directional drilling companies have trained drilling crews to load downhole tools into the bottomhole assembly, allowing the directional driller to be located in a remote center. Applications like this do have the potential of helping operators lower personnel travel-related costs and of improving personnel safety and security in high-risk countries.

Finally, automation is not an all-or-nothing concept. There are many opportunities in between for different levels of automation depending on the drilling environment.

“Automation isn’t the goal at all. Nobody is enamored with automation. What they’re interested in is drilling optimization, and automation is just one of the tools. Though we could end up with man-less rigs, that’s not the goal. The goal is to successfully improve our performance,” Mr Reid said.

In fact, the notion of a totally automated rig – “push a button, drill a well” – may sound appealing to some, but to others, it’s neither appealing nor realistic.

Mr Orr, H&P, is certainly in the latter group: “I don’t know if we’ll ever get there. I use the analogy of aircraft and autopilots. With today’s autopilot technology … you can have a plane and not have a pilot, but I’m not going to get on one. I might have to land in the Hudson (River) every once in a while.”

Reference: SPE/IADC 119965, “Multiparameter Autodrilling Capabilities Provide Drilling/Economic Benefits,” Fred Florence, Michael Porche, Randall Thomas and Ryan Fox, NOV M/D Totco, 2009 SPE/IADC Drilling Conference & Exhibition, Amsterdam, 17-19 March 2009.

FlexRig is a trademarked term of H&P.