Despite challenges, lure of Latin America too strong to ignore

Abundant resources, from Brazil to Argentina to Guyana, will drive industry to push past geopolitical and fiscal uncertainties to sustain long-term investments

By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

In 2014, an investigation by the Brazilian federal police, dubbed Operation Car Wash, raised suspicions that several politically appointed Petrobras executives had been accepting bribes in exchange for offering construction and engineering companies inflated contracts. Portions of these ill-gotten gains were allegedly paid to politicians and their political campaigns.

Dozens of elected officials were still under investigation as of early August, and multiple arrests have been made. As a result, Petrobras did not publish its Q4 2014 financial statements until April 2015 because PWC refused to certify the statements until Petrobras revalued its assets to reflect the alleged bribes. When the statements were finally released, they included a $2.1 billon write-down for the inflated contracts.

Despite this corruption scandal rocking the Latin American oil giant, experts believe that it will not diminish Brazil’s importance to the global E&P market in the long term. Brazil’s offshore presalt fields contain an estimated 65 billion bbl of recoverable resources, according to Pre-Sal Petroleo SA (PPSA), the organization created in 2013 by the Brazilian government to oversee presalt production trading contracts. Foreign oil companies are unlikely to shy away from working with Petrobras, which they must do in order to explore the presalt, according to Jorge Piñon. Mr Piñon serves as Director of the Latin America and Caribbean Energy Program at the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin. “Brazil is too big to ignore,” he said. It is also worth remembering, he added, that the majority of the company’s thousands of employees were not involved in the scandal.

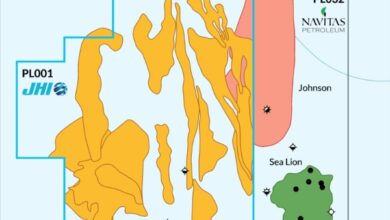

Brazil is not the only Latin American country with E&P opportunities, however. Shale exploration continues to ramp up in Argentina, which holds the second-largest shale gas and fourth-largest shale oil reserves in the world, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Promising discoveries have also been announced this year in Guyana and the North Falklands Basin, by ExxonMobil and Premier Oil, respectively. Farther north, Mexico’s energy reforms are opening additional exploration opportunities by allowing foreign oil companies to operate in the country for the first time in 75 years.

These opportunities signal long-term optimism. In the near term, though, the global oil price slump is taking its toll on drilling activity. The Latin American rig count was 314 in June, down from 398 a year ago, according to the EIA. In Brazil specifically, the rig count was down to 52 – 28 semisubmerisbles, 22 drillships and 2 jackups – by July 2015. That’s compared with 67 rigs in July 2014 and 84 rigs in July 2013, James Hearn, Analyst for Infield Systems, said.

That’s not good news, but it’s also not indicative of a dire outlook, experts say. Operators are likely to remain future-focused, even if they are cutting CAPEX now. “The industry is not asking, ‘What is the price of oil today?’ The industry is asking where the price of oil will be three, five, seven years from now,” Mr Piñon said. “Oil companies are not going to hold back growth because when the market gets to $100/bbl, that’s not when you start drilling. You start drilling now in anticipation of where the market is going to be long term.”

Prominence of presalt

Presalt fields are playing an increasing role in Brazil’s oil production. In October 2013, presalt production averaged 303,000 bbl/day and accounted for approximately 15% of total oil production. By 2020, presalt oil is projected to make up 50% of Petrobras’ production, according to the company’s 2015-2019 business plan, announced in June.

Although the rig count in Brazil has fallen by a third since 2013, many of the rigs that remain working are those in the presalt due to the high production levels there, Justin Smith, Senior Rig Specialist, IHS, said. “While it isn’t cheap to drill in the presalt, it’s the most productive. One well in the presalt just produces so much more than a number of wells in a more traditional field.” Earlier this year, Petrobras reported that the average daily production from a presalt well is 25,000 bbl/day – some even go up to 30,000 bbl/day.

This type of production potential will keep not just Petrobras but also other companies interested in the presalt, despite current economic circumstances. “The huge potential resources, together with institutional stability and a well-established regulatory framework, make the Brazilian presalt very attractive to new investments in the mid- and longer terms,” PPSA President Oswaldo Pedrosa said. “Even in the short term, despite the cyclical downturn of the oil and gas industry, Petrobras and the other oil companies engaged in the presalt exploration and production activities maintain their presalt projects as top priority.”

The first presalt field opened to production sharing under PPSA is the Libra field, which holds 8-12 billion bbl of recoverable reserves, according to the EIA. The field, situated in the Santos Basin, is operated by Petrobras, which holds 40% interest. Mr Pedrosa considers the Libra partnership, formed in October 2013 with Total, Shell, CNPC and CNOOC, to be an important PPSA accomplishment. “The management of the Libra project has been performed in a collaborative joint venture environment with all the members, favoring project performance and transparency in the decision-making process.”

Libra’s first appraisal well, NW1, was drilled in 2014. It reached a final depth of 5,734 m in a water depth of 1,963 m and confirmed the presence of a 290-m oil column. Seadrill’s West Tellus and West Carina drillships are currently contracted to carry out further appraisal drilling on the field.

One of the biggest challenges in presalt is developing technologies that can lower costs without compromising safety and environmental compliance, Mr Pedrosa said. “As we consider the relevance of well construction costs in the presalt fields, major efforts will have to be conducted toward the development of new cost reduction techniques, especially those for drilling in very thick salt layers,” he said. “New rig concepts, automation, managed pressure drilling and new materials could be listed among the main points in the industry’s wish list.”

Although Petrobras has seen successes in developing presalt technologies, Mr Pedrosa believes further innovations are needed to allow improved exploration in the presalt layers and production from thick, heterogeneous carbonate reservoirs. Key areas are “equipment and systems for very high productivity wells, smart well completions, new subsea technologies, large-capacity FPSOs, complex gas processing and separation units and cost-competitive gas utilization systems, among others,” he said.

Problems for Petrobras, problems for Brazil

Analysts say Brazil’s rig count began declining as early as mid-2013. This, Mr Smith of IHS said, is because Petrobras is the most indebted oil company in the world. “They’re massively indebted, so they’ve been trying to shed costs,” he explained. Part of this indebtedness is due to the Brazilian government’s requirement that the company subsidize the cost of fuels in the country.

In 2010, the Brazilian government instituted a requirement that Petrobras be the operator and hold at least 30% interest in all presalt projects. This exerted an additional financial strain on the company. “All these changes … put a heavy burden on Petrobras,” Dr Francisco Monaldi, Latin American Energy Fellow at the Baker Institute of Public Policy, explained. When the corruption reports began surfacing last year, the company’s position worsened.

The silver lining to these problems is the industry has a tendency to learn and grow from difficult situations. Mr Piñon said he believes the oil and gas industry will grow from this scandal, as it did after Exxon Valdez and Macondo. “All of these events make the industry a much stronger industry. It adds transparency, responsibility and accountability,” he said. “It wakes us up to be better and more responsible operators. I think once we go through this difficult process in the next year or so it takes for the Brazilian government and Petrobras to get their house in order, they are going to come out a much better company.”

In February, Petrobras announced that Aldemir Bendine, former Chief Executive of Banco de Brasil, was taking over as Petrobras CEO. Mr Bendine told the Brazilian newspaper “O Estado de S.Paulo” in August that he believes it will take the company five years to recover from the corruption charges.

In the meantime, Petrobras will continue to cut costs. In June, the company released a new business plan that projects a 40% spending cut starting this year. It also scaled back the company’s production forecast from more than 5 million BOED in 2020 down to 3.7 million BOED.

The spending cuts have already begun to take effect, Mr Smith said, as Petrobras has allowed rigs to roll off contract without renewals and has announced approximately $13.7 billion in divestments. The divestments are divided among exploration and production (30%), downstream (30%) and gas and power (40%). In July, Petrobras sold 20% of its stake in the concessions of Bijupirá and Salema fields in the Campos Basin as a part of this divestment plan. The transaction was worth $25 million. As a result of these divestments and cuts, Mr Smith forecasts Brazil’s rig count to continue to slide slightly over the next two years.

In addition to not renewing some rig contracts, Petrobras also canceled five out of six rig contracts with Brazilian drilling contractor Schahin in May. The contractor was experiencing its own financial problems and had to take the five rigs out of service for a month. During that time, as a part of its ongoing effort to manage costs, Petrobras canceled the contracts for all five of those rigs – three drillships and two semisubmersibles. Two of the drillships had contracts that extended out to 2022.

Activity from IOCs is unlikely to offset Petrobras’s cuts sufficiently to keep the rig count in Brazil steady. Total and Premier Oil, for example, both own blocks in the Foz do Amazonas Basin off Brazil’s northeastern coast, near the border with French Guiana. However, Mr Smith said, there would likely not be any activity in these blocks before 2016. Even accounting for this activity, he continued, the rig count in Brazil will likely still drop slightly before leveling out.

Dayrates have fallen, too, as they have in other markets around the world. Any new contract signed in Brazil in the current environment would command a rate of only $300,000-350,000, Mr Smith said. “The days of signing $600,000/day contracts are gone, at least for a while,” he said. In fact, there have been no new rig contracts signed at all in Brazil this year.

Mexico takes the stage

EIA data shows that Mexico’s production has steadily decreased since 2005. In 2013, the country produced an average of 2.9 million BOED – its lowest output since 1995. Production fell even further in 2014, to 2.4 million BOED, according to Pemex data. Rig count has also declined – averaging 88 in 2014 compared with a high of 124 in 2009.

To reverse these declines, Mexico reformed its energy policy in 2013, opening itself to foreign investment for the first time in decades. “They have had a difficult time the last couple of years,” said Mark Edmunds, Global Lead Client Service Partner and Vice Chairman for Deloitte. “They’re producing less oil. They need a lot of help and a lot of foreign capital to come in and develop their rich resources so they can get into a net export position and be a more powerful energy player.”

One round of bidding that was open to foreign companies – offering 14 shallow-water blocks – has already been conducted under the reforms. Only two blocks were awarded, however. Both were won by a consortium made up of Siera Oil and Gas, Talos Energy and Premier Oil.

A combination of unappealing commercial terms and the fact that many operators are holding out for the deepwater blocks to be auctioned later this year likely contributed to the low activity level in this round, Mr Piñon said. “I think we’re all disappointed that this Round One was not as successful as people expected, but I think that Mexico learned that they have to make contracts more attractive, and you’re going to see some changes for the next round,” he said. “Also, the concession areas that were put forward in these bids were not that attractive.”

The Mexican government is currently assessing and revising terms for future bidding rounds, including deepwater and unconventionals. Mr Edmunds said the deepwater bidding round will likely be delayed by a few months while the government establishes new terms, while the unconventional round “should follow that by a few months, although it could be further delayed due to the higher recovery costs and low prices keeping bids down. We should have a better idea of timing in the next few months,” he said.

Independents that have expertise drilling unconventional plays in the US and Canada will likely seize the opportunity to do the same in Mexico, he added, particularly in formations that are similar to ones they’re already drilling. The same goes for deepwater operators, and that’s good news for Mexico. Deepwater is where Mexico and PEMEX can really benefit from the experience and knowledge of companies that have been successful in similar formations, Mr Edmunds explained. Deepwater operators have already developed the processes and technologies to drill in some of the US Gulf’s high-pressure, high-temperature deep and ultra-deepwater formations. “They’re going to find a lot of offshore plays that are very similar to resources they’ve already exploited in the GOM,” he said. “It’s never exactly the same, but I’m sure they’ll find a lot of similarities and use a lot of the same techniques and the same drilling contractors to help them.”

The flow of expertise into Mexico will also translate into new technology facilities and corporate offices in Mexico City and a boom to Villa Hermosa, a major staging area for Mexico’s offshore activities, Mr Edmunds said.

Looking to the future, Mexico has an opportunity to be seen as a significant competitor to Brazil for operators’ attention – if it handles its reforms appropriately. “Mexico has become a formidable competitor for Brazil at this point, even though Mexico hasn’t yet started auctioning off the deep offshore areas that could be a sort of competition for the presalt in Brazil,” Dr Monaldi said.

Mexico’s proximity to American oil and gas infrastructure, as well as operators’ existing knowledge of the GOM, both add to Mexico’s attractiveness to some operators. “Mexico has a relative advantage over Brazil because the GOM geology is known and the proximity to the US is very beneficial,” Mr Piñon said. “The synergies of Mexico and the US working in a common area such as the GOM are going to make Mexico more attractive than Brazil.”

Argentina’s unconventional growth

Like Mexico, the Argentine government has reformed its energy policy to encourage foreign investment. Two years after the national government expropriated Repsol’s shares of the national oil company YPF, the country reformed its hydrocarbons laws in 2014 to encourage foreign ventures in unconventional plays. The minimum investment required for a company to be exempt from export controls has been lowered from $1 billion to $250 million. The reforms also extend the length of unconventional concessions to 35 years.

Argentina holds the world’s second-largest technically recoverable shale gas reserves at 802 trillion cu ft, according to the EIA. YPF is hoping to exploit those reserves with the help of international partners like Chevron, Mr Edmunds said, in order to become a net energy exporter.

Unlike a lot of other countries, Argentina has seen its rig count hold relatively steady through the current downturn – it was 107 in June 2014 and 105 in June 2015, according to Mr Edmunds.

Not only is there a greater demand for rigs to develop Argentina’s unconventional resources, local contractors are also looking to upgrade their fleets with new technology. San Antonio International, which has 53 drilling rigs and 124 workover and pulling rigs across Latin America, recently deployed a newbuild National Oilwell Varco Ideal Prime 1500 rig in the Vaca Muerta shale in the Neuquén province. The company will likely order four more high-tech rigs for Southern Argentina next year, Edgardo Lorenzo, North District Manager for San Antonio, said.

The newbuild rig, SAI 651, is working for Pan American, Argentina’s second-largest operator behind YPF. It is San Antonio’s first walking rig, although its fleet already contains skidding rigs. SAI 651 can walk 120 ft along the X axis and 40 ft along the Y axis with a full setback.

As activity in Argentina’s unconventional plays picks up and international contractors, such as Nabors and Helmerich and Payne, bring in their high-spec rigs, competition is ramping up. Mr Lorenzo said local contractors are recognizing that they have to high-grade their fleets. “As the Vaca Muerta shale or other unconventional plays are being developed, all the customers that are going to drill in that place are demanding new technology,” he said. “We can drill a well in the Vaca Muerta shale with a conventional rig, but most of the customers prefer to do it with new or high-technology rigs.”

Simultaneous to the introduction of new rigs, older rigs in San Antonio’s fleet must remain working. The capabilities of these rigs vary – some are mechanical, some DC-powered, others AC-powered. Some are equipped with top drives, while others are not. Overall, Mr Lorenzo said, about 10% of San Antonio’s drilling rigs are considered high tech. These newer rigs, such as the Prime 1500, can drill as deep as 18,000 ft. That capability isn’t needed in all plays but is regardless seen as useful in the Vaca Muerta, where wells are drilled to between 10,000 and 12,000 ft. “We’re relocating older rigs in the country to other areas of Argentina where the drilling demands and the depths of the wells are lower, or the operators don’t need such technology to complete their projects” Mr Lorenzo said. “There are also always customers that prefer to continue drilling with the older rigs because they don’t have enough activity to ensure to a drilling contractor that high-tech rigs will work continuously or at least in a long-term contract.”

To date, NOV has delivered only one other Ideal Prime 1500 rig to Latin America. That was to Colombia in 2014. It has, however, delivered eight other Ideal series rigs to drill in the Vaca Muerta over the past two years, said Tom Hand, NOV Director of Business Development in Canada and Latin America. The 1,500-hp Ideal Prime rig includes an optional walking system.

All of the Ideal rig series, including the Ideal Prime 1500 rig, are equipped with the NOV AMPHION drilling control system. “The control system is really well-suited for shale drilling, for reaching out in those long laterals,” Mr Hand said. “The system has had great success for reducing torque and drag for those long-reach wells.” The integrated system provides control over the drawworks, mud pumps and top drive from the driller’s cabin. It also allows simultaneous monitoring of drilling functions. NOV has sent AMPHION simulators to Argentina to provide training to crews working in the country.

Once oil prices return to higher levels, NOV expects demand for advance-technology rigs – as well as downhole equipment – to pick up. “We believe that drilling contractors and oil producers will be switching to new technologies,” Stanley Gibbs, NOV Vice President of Operations in Latin America, said. “It isn’t just rigs but also technology associated with drilling tools, with new fluid controls or new fluids that we’re bringing to the market.”

Changing the rules of the game

Although Argentina’s rig count has stayed relatively stable and the high-grading of the rig fleet has resulted in a demand for new technologies, the country’s upcoming elections are stirring worries of instability. Some believe the elections could result in more energy policy changes, Mr Edmunds said. “Economic stability is the big issue. The elections later this year are top of mind for foreign investors interested in Argentina,” he said.

Other countries in Latin America are also being watched for possible energy reforms – mostly to the benefit of the industry, however. The decline in oil price means governments are becoming more willing to do much more than before in order to attract foreign investment. “With low oil prices, these commercial terms matter,” Mr Edmunds said. “When people allocate their precious capital to different projects, in some cases, it can tip the scale to that country.”

A country’s local content requirements, for example, can impose significant added costs for an operator. Brazil has some of the most stringent local content requirements in South America – up to 70% local content is required on some projects. “The local content rules almost end up being an additional tax that companies have to pay because they are very hard to fulfill,” Dr Monaldi said. In other countries, like Colombia, he added, local content rules are often more loosely enforced, thereby placing less of a burden on foreign companies.

With other Latin American countries sweetening their commercial terms, coupled with the fall in oil prices, Brazil may be forced to revisit its own terms. “I think they will slowly and gradually go in the direction the rest of the region is moving, particularly if the oil price remains at these levels,” Dr Monaldi continued. While oil prices are low, he said, companies are going to be more careful and selective in their spending and may opt to invest in countries where it’s less expensive to operate. However, even when oil prices rebound, if Brazil’s terms are not competitive with those offered by other countries in the region, the government may still have to consider reforms. “I think domestic issues with Petrobras and the competition from other countries will probably even force them to reform at higher oil prices.”

Dr Monaldi believes the country is more likely to relax local content requirements than to change its production-sharing terms. The latter would be more visible and politically costly for the governing party, which introduced the requirement that Petrobras operate and hold at least a 30% equity in presalt projects. Still, both reforms are on the table.

For oil companies, this is a good time to work with host countries, as well. As countries like Brazil, Mexico and Argentina seek international partners, IOCs can potentially have some level of influence on the countries’ policies. “It’s an opportunity for the private sector to have an open conversation with governments about what they expect, what they can afford, what they can contribute and how to establish a long-term relationship with the industry,” Mr Piñon said.

It is also important, he added, that host countries offer continuity to their investors and don’t change the rules of the game in the middle of play. “Once a host country establishes what the rules of the game are and the international oil companies come in and invest under those rules, it is totally unfair to all of a sudden change the rules of the game,” he said.

Despite this, there have been instances where a country has radically reformed its energy policy in ways that benefit the country at the expense of foreign companies – and yet companies still invested. This occurred in Argentina when YPF was nationalized, and in Brazil when the government introduced rules that required Petrobras to be the operator in all presalt projects.

There’s no guarantee that these countries won’t do similar things again, Mr Piñon said. However, “they keep coming back because the prize is so big,” he added. “The potential in Argentina for shale is huge; the potential in Venezuela with heavy oil is huge; the potential in Brazil for offshore is huge. That’s why they come back. They come back and have to take that risk.”

Opportunities in the distance

While the low price of oil is making some operators slow to commit investments, others are taking action to benefit from lower buy-ins. Australia-based Karoon Gas is one such company. “In Brazil, we are progressing quickly. A depressed oil market is assisting Karoon in achieving lower rates for its materials and services leading into 2016,” Tim Hosking, South America General Manager, said. Costs have fallen by approximately 30% during this downturn, he added.

In 2010, the company conducted its first wide azimuth 3D seismic survey in Brazil. The survey covered the five blocks Karoon acquired in 2008 in the Santos Basin, 260 km from Navegantes and off the coast of Santa Catarina State. Then in 2013, the company began the first phase of exploration drilling on blocks S-M-1101 and S-M-1165 on the Kangaroo field and block S-M-1166 and S-M 1037 on the Bilby field. Of three wells drilled, two of them – Kangaroo-1 and Bilby-1 – yielded oil discoveries. Karoon encountered a 25-m gross oil column in Kangaroo-1, with samples showing 42º API oil. In Bilby-1, Karoon encountered a proven oil column of 320 gross m with 33º API oil.

During this exploratory campaign, Karoon essentially encountered a new play type, Mr Hosking said. “We’ve basically found a new play type in the Santos Basin, which is the Paleocene restriction play,” he said.

The second exploration phase, using the QGOG Constellation Olinda Star semisubmersible, kicked off in November 2014. Once again, two discoveries were made. A second Kangaroo exploration well confirmed a 250-m gross, 135-m net oil column with 39º API crude. The Echidna-1 well, drilled in Block S-M-1102 on the Echidna field, encountered a 213-m gross, 104-m net column. Oil samples measured 38.6º API. The flow test conducted on Echidna produced a facility-constrained stabilized flow rate of 4,650 bbl/day over 2 hours from the Paleocene reservoirs, with a flowing wellhead pressure of 504 psi on a 1-in. choke. “Test results confirm that the quality of the Paleocene reservoir, previously interpreted from mud log and petrophysical data, is better than that observed anywhere else in Karoon’s Brazilian exploration acreage,” Mr Hosking said.

In 2016, Karoon plans to drill at least two appraisal wells either on the Echidna field to confirm the field size or on Kangaroo, depending on the findings. Eventually, the operator envisions building a production hub in the Santos Basin to connect all five of its prospects in the area. In addition to Kangaroo and Echidna, the company owns interest on the Kookaburra, Bilby and Platypus fields. “We’re gearing up to start the appraisal program in the first quarter of 2016 to discern the size of our discoveries and hopefully move on to bigger and better things throughout the program and get ready for first oil in the near future.”

Karoon Gas is also gearing up for exploration offshore Peru, with its first well planned for 2016. It will be the first well in water depths greater than 623 ft (190 m) in the country’s history, Mr Hosking said. The well will be on Block Z-38 in the Tumbes Basin, 6 miles (10 km) off the Peruvian coast. “They’ve only drilled in shallower depths. A lot of the existing wells have only been drilled in 50 or 60 meters of water depth, so there’s no infrastructure,” he said. This means Karoon will need to bring in supply vessels, as well as a multitude of equipment. Karoon is currently planning to drill two additional wells in the basin, to be drilled after the first 2016 well, in waters ranging from 1,148 ft (350 m) to 2,296 ft (700 m).

Karoon first established its presence in Peru when the company opened a regional office there in 2008. In 2010, it conducted a seismic survey of Block Z-38, which covers an area of 3,029 miles with water depths ranging from 1,148 ft to 3,280 ft. The company was attracted to Peru, Mr Hosking said, because of its underexplored hydrocarbon basins.

A critical challenge Karoon has encountered in Peru is having to essentially educate local authorities and regulators about drilling in deeper waters. “We’re working very closely with the Peruvian government to obtain all the necessary approvals and to educate them on what our plans are for Peru and explain to them how the offshore industry works in places such as Brazil, the Gulf of Mexico and offshore Australia to ensure that we implement a world-class drilling program,” Mr Hosking said.

Besides Peru, underexplored basins abound across Latin America, offering significant potential. Countries such as Guyana have seen more drilling activity in the first half of this year than in years past, Mr Smith of IHS said. “Part of the reason is because northern South America and the eastern side of Brazil at that Atlantic margin has a similar geology to what they have in West Africa,” he said. “There have been a number of decent discoveries there. People seem to be pretty optimistic about those countries in the future.”

One of these discoveries was made by ExxonMobil in May in the Stabroek block, 120 miles off the coast of Guyana in 5,719 ft water depth. The Liza-1 exploratory well was drilled by the Transocean Deepwater Champion drillship and encountered 295 ft of oil-bearing sandstone reservoirs. Another discovery was announced in December 2014, when Petrobras, in partnership with Ecopetrol and Repsol, struck natural gas in the Tayrona Block, 24.9 miles off the coast of La Gaujira, Colombia. The Orca-1 well was drilled to 13,910 ft and encountered natural gas at 11,811 ft. Petrobras, in a press release, said the well marked the first discovery in the history of Colombian Caribbean deepwater exploration.

Although the vast majority of Latin America’s untapped hydrocarbons will remain locked in for the next few years, analysts believe the region will see a flurry of activity when prices climb higher. “I think a lot of people talked about Latin America at the start of 2014 as being the shining light frontier region,” Mr Hearn of Infield said. “I think that still exists, and the region still holds a lot of potential… I would expect oil prices to pick up around 2017 onwards, and then you’re really going to see the region come to the fore again.”

Ideal and AMPHION are registered terms of National Oilwell Varco

Click here to view an online exclusive article with the mayor of Macaé, Brazil, discussing how Brazilian cities are dealing with the surge in drilling activity in recent years.