Coiled tubing pushing its limits by going bigger, expanding niche applications, thinking riserless

By Katie Mazerov, contributing editor

It entered the marketplace on the fringe, a tool for sand clean-outs in Louisiana. Now, nearly 50 years later, coiled tubing has become a workhorse, increasingly used in drilling, completions and interventions, particularly for horizontal and deviated wells and in tight shale formations. It’s also being pushed to its limits, maybe even beyond.

“There has been a steady progression of improvements in both CT material and manufacturing processes over the last two or three decades, so that it now is very reliable and predictable,” said John Misselbrook, senior adviser, coiled tubing, BJ Services. “The key thing that CT does is work on live wells; it’s designed for that.”

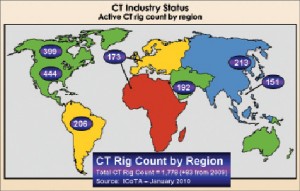

Ed Smalley, general manager, NOV CTES (National Oilwell Varco/Coiled Tubing Engineering Services), said coiled tubing has been a key technology in the “hotbeds of activity” for North American unconventional gas production, including shale, tight-gas sand and coalbed methane wells. Worldwide, coiled-tubing units number more than 1,700, about half in North America.

Advancements in the last 10 years in manufacturing, inspection and quality-control methods are among the technologies that continue to help move CT forward. “The CT mills have done an incredible job over the years in making these improvements so the industry is getting what it needs in terms of reliable material characteristics,” Mr Smalley noted.

“Now the CT industry is shifting our focus toward better and smarter ways to apply that material in the field. Oilfield personnel who, in the past, may have not readily embraced control systems are starting to see that putting a good electronic control system on a piece of field equipment is like having your best operator on location every day.”

In addition, he continued, “emergency stop safety systems are increasingly being used on coiled-tubing units to prevent the units from over-pulling or over-snubbing the pipe.”

Coiled tubing has played a significant role in fracturing applications in unconventional shale gas production. “This has been a growth area for CT,” Mr Misselbrook noted.

An example involves the milling of frac plugs. “A lot of these wells have multiple plugs and multiple zones in the long horizontal laterals that are fracture-stimulated separately,” Mr Smalley said. “Coiled tubing is proving to be a more cost-effective way to mill out those frac plugs when the stimulation operation is completed and the well is ready to be placed online.”

Another improvement in coiled tubing is that it’s getting bigger. “Five years ago, the most common size of CT was 1 ½-in. OD,” Mr Misselbrook said. By 2008, the most common size was 1 ¾ in., and the most common size is now 2 in. A typical range will run from 1 in. to 2 7/8 in.

The number of horizontal and deviated wells being drilled that need intervention is driving the increases in diameter. Mr Misselbrook said. Bigger diameter makes the pipe stiffer to more easily reach into deeper horizontal wells.

Downhole agitator tools, designed to reduce high friction forces that limit the length that the coil can be pushed in high-angle wells, is also a key enabling technology that has recently come on the scene.

“One of the limitations of coil in a highly deviated well is that you will ultimately reach a lock-up condition, where the coiled tubing actually forms a helix inside the casing and high wall-contact forces prevent any additional forward movement of the tubing. Agitator tools can greatly delay the onset of this lock-up condition, allowing the tubing to be successfully deployed at greater depths in high-angle, extended-reach wells,” Mr Smalley explained.

As fluid is being pumped inside the CT, an agitator, a device installed on top of the BHA, creates a gentle pulsation at the bottom of the tubing. “The pulsing action helps reduce the friction between the tubing and the casing wall, so now we can get a lot farther out with the same size CT,” Mr Smalley continued. “In addition, new software programs can actually model how much farther the coil can be pushed when using these tools.”

But coiled tubing has its limits, which are becoming more apparent as operators venture into deeper subsea and offshore oilfields. “When we get to wells with true vertical depths over 30,000 ft, that is a limitation,” Mr Misselbrook said. The strength of the low-carbon and low-alloy CT steel poses challenges at greater depths because fatigue life diminishes with increasing strength.

“When we’re running coil into the well, the tubing has got to support its own weight,” he continued. “Currently, the proven established CT steels that have acceptable fatigue properties have working yield strengths around 110,000 psi. Drill pipe, on the other hand, is available in grades that are 25% stronger and hence can work 25% deeper.”

Subsea wells also normally require a MODU to support the large load imposed by the intervention riser. “The issue of intervention in a subsea well is finding a way to do interventions that don’t need an expensive semisubmersible or floating rig,” Mr Misselbrook said. “There is a lot of interest in using CT for re-entering wells, but the challenge is deploying the coil without using a riser,” he continued. “A conventional riser requires a big, expensive vessel. So a number of companies are engaged in developing concepts to explore riserless intervention operations using CT.”

NOV CTES and others in the industry are working on a self-standing riser design that connects to the sea floor and extends up to about 100 ft below the water’s surface. A balloon-like ballast container at the top supports the weight of the riser so it no longer has to be supported by a drilling unit.

“Wells in the Gulf of Mexico can become cost prohibitive to operate because of the need to use the more expensive mobile offshore drilling units to perform a CT intervention operation,” Mr Smalley said. “We believe this self-standing riser concept, coupled with a coiled-tubing operation from a small vessel, can cut the intervention costs at least by half and probably more,” he added. “If we can reduce this cost, these GOM wells will remain productive over a longer period of time.”

Another advance that is likely to drive the use of CT involves real-time information systems based on fiber optics or electrical conduits, Mr Misselbrook said, noting he is optimistic about the progress the industry is making.

“This will be an important step forward. We are looking to add more feedback from the tools on the bottom of the coil,” he said. “Pushing three or four miles of coil into a well using surface gauges to try and deduce what is going on downhole is not the same as having a sensor package at the bottom of the coil that is actually telling you what is happening.”

And, with coiled-tubing units having increased internet access on location, more real-time data transmission back to the customer’s office during a CT job is now a reality. “In a fracturing operation, many times the operator wants to monitor pressures, rates and total volumes being pumped in the wells,” Mr Smalley said. “With this technology, operators no longer have to go to the location to monitor the field operation in real time.”

NOV CTES builds the data acquisition systems that attach to the CT units and provides the software that tracks fatigue on the coil so operators will know when to replace it, avoiding a failure break.

There is also increasing focus on achieving more efficient field operations and utilization of equipment. “A lot of what we do with coil in fracturing operations involves pumping nitrogen or abrasive slurries downhole,” Mr Smalley said.

But the abrasive fluids, as they are being pushed through the pipe spooled on the reel at surface, can preferentially erode the outer layer on the inside of the coiled tubing due to centrifugal force acting on the slurry. New ultrasonic tubing monitoring technology provides real-time wall thickness measurements during the field operation, enabling the user to monitor for this condition and take the appropriate action.

Another emerging technology is automation of the nitrogen vaporization process, which requires heating of the liquid nitrogen on location. “People are now realizing the value of vaporizer automation systems, where the control system operates so efficiently it extends the life of the pumps and other equipment and uses less fuel,” he explained. “In cases where the heat source is a direct-fired vaporization unit, the automation system can also provide an added benefit of burning environmentally cleaner.”

As the industry continues to develop tools and technologies to improve coiled tubing and expand its applications, the objective remains to produce more reserves in a cost-effective and efficient way.

“Producers are driven by one goal: to reduce the cost of drilling, completing and operating the well once on stream,” said Mr Misselbrook. “All service providers are confronted with this continuous requirement to find new ways to drive down costs. This is especially true today in North America, where gas prices are very low and operators have less revenue to spend on drilling new wells and are constantly striving for ever greater efficiency.”

Hi

good day pleas con you send me cours about coiltubing and calculated of pumping