As operators reshuffle priorities, offshore exploration is losing out

Development drilling is likely to increase, but it can’t offset a bigger reduction in exploration drilling in 2020

By Linda Hsieh, Editor & Publisher

The attacks on two Saudi Aramco oil facilities on 14 September took out approximately 5.7 million barrels per day from the global oil supply, leading to a quick spike in oil prices to nearly $70 in the second half of September. However, by early October, things seemed to be back to business as usual, with oil prices settling down into the $50s.

“Of course, a large portion of the increase in oil prices was a risk factor premium,” said Audun Martinsen, Partner and Head of Oilfield Service Research for Rystad Energy. “It will be a short-term challenge to meet the world’s oil demand because you have removed 5.7 million barrels per day from Saudi Arabia, but we have to wait and see what happens over the next days and weeks and see how quickly they can resume production.”

If the challenges and conflicts in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East escalate, that could lead to higher oil prices into 2020. However, barring any real changes in the fundamentals of the oil and gas industry, Mr Martinsen said he is forecasting oil prices to average $60 Brent and $54 WTI in 2020.

“The fundamentals point in the direction for a weaker market next year, and I would say that drilling activity is likely to stay flat or potentially come down.”

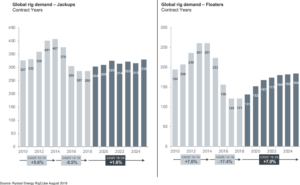

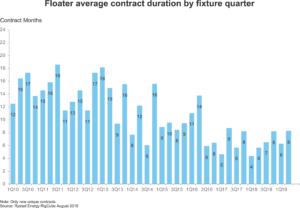

Most notably, Mr Martinsen said he believes that offshore exploration will take a hit in 2020, which will bring down overall offshore activity levels despite an increase in development drilling.

“Exploration is just not being prioritized by operators,” he said. A discovery that is made in 2020 likely won’t begin producing until 2030, and it’s very uncertain what the oil price will be or what the macro environment will be like by then. “It’s a question of how relevant offshore will be and how cost-competitive offshore can be in 10 years compared to shale, which is now producing far below its potential… In a cost-conscious environment, operators have to put their dollars where they will get the best returns.”

Rystad Energy is forecasting that 580 offshore wells will be drilled in 2020, including 360 development wells and 220 exploration wells. That compares with 610 total wells in 2019, including 330 development and 280 exploration. “As these numbers show, most of the decrease will come from the exploration well segment.”

One piece of good news is that, even though he expects rig demand to fall slightly in 2020, dayrates will likely not follow suit. “We expect the average offshore dayrate to either stay flat or trend slightly higher,” Mr Martinsen said. Harsh-environment rigs are already up to around $300,000-per-day contracts and will likely see bumps of 5-10% in the coming year, he said. Rates for other floaters will probably not see much movement, staying at around $200,000 for drillships and around $150,000 for semis. However, new deepwater campaigns in Latin America and Africa could boost demand for these rigs.

“It will be more challenging for jackups, where dayrates will stay more or less where they are now – about $100,000 for high-spec jackups and anywhere between $50,000 to $70,000 for the other units,” Mr Martinsen said.

Removing additional rigs from the global fleet could help dayrates, of course, and Mr Martinsen said he believes the industry stands to scrap at least 100 more rigs on top of the 180 that have already been removed since 2014.

“Last year we had around 300 units, including jackups and floaters, that were stacked. This year, that has come down to around 220 units. So, we have scrapped more rigs this year, but hopefully they will remove even more next year.”

Operator spending and costs

Operators’ 2020 CAPEX levels are expected to fall by 1% for offshore, 3% for conventional onshore and 8% for onshore shales, according to Rystad. “We have said that activity is going to be coming down a little bit, and dayrates will be improving a little bit, so that means drilling CAPEX will be more or less flat next year,” Mr Martinsen said.

On the other hand, offshore breakeven prices are likely to increase in 2020, after staying flat in 2019. “It seems that inflation is now going to occur, with a little bit more expensive engineers, a little bit more expensive subsea, and dayrates for rigs coming up slightly,” Mr Martinsen said.

“I think it’s going to be a little bit more expensive to develop offshore resources in 2020.”

To offset inflation, the industry will have to look to new places for further reductions. “Offshore has been drilling faster and more efficiently, and we’ve already seen costs come down by about 30% – but up to now it hasn’t necessarily been because of automation or digitalization. I think we will start to see more efficiency improvements related to automation and digitalization start to happen as we move into the next decade.” DC

This article includes reporting by DC Contributor Emily Lincke.