All shales are not equal: Emerging resource prompting customized completion solutions

By Katie Mazerov, contributing editor

There is new abundance in the land of plenty. This time the bounty is not in amber waves of grain, but in the vast and resource-rich plays of US land shales, where emerging technologies are recovering increasing supplies of natural gas.

Still considered “unconventional,” shale-gas production has boomed in recent years in the Big Four plays – Barnett, Fayetteville, Haynesville and Marcellus, – and others, such as Woodford. Haynesville and Marcellus, the two new plays, have now been joined by yet another: Eagle Ford, which extends from the Mexican border of southwest Texas into Louisiana, underlying the Austin Chalk.

“Shale is a game changer in that it represents a new paradigm in our nation’s energy portfolio,” said Chip Minty, a spokesman for Devon Energy, the first company to commercially produce natural gas from shale and the largest producer in the Barnett Shale, as well as one of the first operators to tap the Haynesville.

“In this day of concern over climate change and emissions, natural gas has the potential to play a role as an energy source that we can rely on for the next 100 years,” he continued. “Shale, a very tight, dense rock with little porosity, was not viable three, four years ago.”

Indeed, a report released in June by the Potential Gas Committee (PGC), affiliated with the Colorado School of Mines in Golden, Colo., estimates the nation’s total natural gas resource base at 1,836 Tcf, the highest evaluation in the committee’s 44-year history. The increased assessment is primarily the result of a re-evaluation of shale-gas plays throughout the United States.

“Shale wells have been around since 1821, when the first gas well was drilled in the United States,” said Dr John Curtis, professor of geology and geological engineering at Mines and director of the Potential Gas Agency, which provides guidance to the PGC. “We have known of the vast amount of gas-in-place for many years, but the gas has been marginally economical to produce in all but a few basins. New and improved technology is allowing us to access this very tight rock and enable the ‘unconventional’ gas-in-place to be converted to produced gas at a reasonable cost.”

Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing are standard practices in shale-gas production. But the similarities end there, as the mechanics and chemistry of the rock vary. “Every shale formation is unique,” Mr Minty said.

“And every time you begin to produce from a new shale formation, you have to spend some time understanding its unique qualities and what kinds of innovations need to be applied to make the best, most productive and economical well you can. We can drill a well in the Barnett, but we can’t take those same drilling and completion techniques to the Haynesville and expect to create a well that is just as productive, because the rock is different.”

Haynesville, in northwest Louisiana and East Texas, is a deep play characterized by high pressures and hot temperatures that must be considered when assessing equipment needs and safety. The Marcellus, a diverse, low-density, 54,000 square-mile play extending from New York into Pennsylvania, West Virginia and parts of Ohio and Kentucky, is a mile beneath the surface in some areas, with often hard-to-access mountain regions. While not as prolific as the Haynesville, its proximity to the large northeastern US consumer markets makes it attractive. Eagle Ford, which geologically speaking is the youngest of the major plays, has softer rock than the other regions.

Despite low gas prices, shale-gas exploration accounts for upwards of 75% of Chesapeake Energy’s drilling capital, which includes all the major shale plays. “Haynesville is our largest asset in terms of current rig count, and the most active and fastest growing of all the plays,” said Jeff Fisher, senior vice president, production for Chesapeake. “In terms of gas prices, we’re taking the long view. Our hedging program helps tremendously in allowing us to maintain a steady pace. Right now, we’re in a mode of drilling to prove up and hold the acreage that we have leased and to preserve our long-term asset bases.”

As of 30 July, Chesapeake had 29 rigs operating in the Haynesville, with 36 anticipated in 2010. The company expects Haynesville net gas production to exceed 275 mmcf/day by the end of 2009 and 450 mmcf net per day by year-end 2010. It expects to become the largest gross producer of natural gas from the Marcellus play by the end of this year, with anticipated production at 80 mmcf net per day, and plans to reach 200 mmcf per day by the end of 2010.

“The emergence of shale as an economically viable resource is the result of a marriage of technologies – horizontal drilling and fracture stimulation,” Mr Fisher noted. “On top of that, today we better understand how to orient horizontal wells – what direction to drill them to not only precisely intersect the reservoir but to set up for the optimum fracturing of the rock during the stimulation process. From there, I think it becomes an issue of getting the most efficient completion along that horizontal.”

Water reclamation and recycling and seismic testing are among the priorities for operators and service companies in shale completions, which require millions of gallons of water for one job. In the Barnett Shale, Devon has led the way in water recycling and recovers about 85% of flowback water used during the completion phase. The recovered water is recycled and reused in subsequent shale-gas operations.

A research project Devon undertook two years ago with the University of Oklahoma enhanced the company’s ability to analyze and interpret seismic data to better understand the rock and increase production. “In 2002, we were only able to produce less than 10% of the natural gas in shale,” Mr Minty noted. “Now we’re up to producing about 20% of the gas-in-place, and that’s a huge number,” he said.

An important consideration in shale completions is the estimated ultimate recovery of the wells, which typically have very high initial production rates but also dramatic hyperbolic decline rates within the first year. “Shale wells can produce over 20 to 25 years, but they will require some re-work periodically,” said Rob Fulks, US development manager, special projects, for Weatherford International. Shale accounts for about 15% of Weatherford’s total completions business, up from 1-2% just three years ago.

“We use certain things to compare shales: depth, net thickness, total organic carbon, total porosity, gas content, and then mineralogy,” Mr Fulks said. “But the big issue is the initial production rate. Haynesville is in a class by itself, with wells coming on between 15 and 24 mmcf per day, but then having an 80% decline the first year.” The larger Marcellus play has a larger IP spread of 500,000 to 16 mmcf per day, while Eagle Ford is coming on between 7 and 9 mmcf per day.

Weatherford uses technologies to locate the best pay zones, isolate zones, understand the orientation of fractures and enhance the productivity of propping agents.

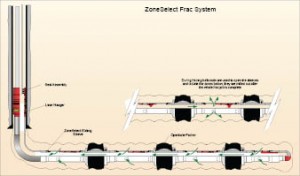

The ZoneSelect system is a completion technology that eliminates perforating and has been particularly effective in cement-less completions in the Marcellus Shale. “The fracture goes out through pre-selected holes in the casing, which have sliding sleeves that are activated,” Mr Fulks explained. “We can open up the zones and fracture through them, and then we can close them off later, which is a big advantage.” The zones are isolated by a series of packers, which can be mechanical, inflatable or swellable.

Weatherford uses technologies in its mud logging portfolio to identify methane-rich zones. “Using our geochemistry in conjunction with mud logging and even LWD, we can now do a much better job of picking the best pay zones,” said Barry Ekstrand, global director of technologies for Weatherford’s Pumping and Chemical Services group.

Microseismic mapping technologies are being used to determine the orientation of fracs to optimize the drainage of the reservoir itself. “We have sensors in the wells, and in real time, while the frac is going on, we can watch how it goes, the direction it is going,” Mr Ekstrand explained.

Chemical technologies to enhance frac fluid flowback are also important. “Pumping a lot of water, which is foreign to the reservoir, is not a good thing, so we need to get it out quickly,” Mr Ekstrand said. “We have developed some surfactant technologies that enhance the flow of the of the frac fluid load back out of the well,” he explained. “We’ve also applied colloidal chemistry to develop materials that coat the propping agents and actually change the surface characteristics such that the connectivity of the proppant is increased.”

Weatherford’s CoMag technology speeds up the settling of particles out of water, a process that has been especially beneficial in the mountainous Marcellus Shale. “We no longer need big settling ponds, so we can treat a lot of water and recycle it very quickly,” Mr Ekstrand said.

In the Haynesville, where high-temperature, high-pressure wells are much like those found in the deep offshore environment, equipment must be rated for surface pressures up to 14,000 psi. “You have to understand the flow rates and pressure the equipment is being subjected to,” Mr Ekstrand noted. “We need equipment rated for the higher frac pressures seen when fracturing in the Haynesville or the incidence of equipment failure will become an issue.”

While shale-gas production is a hot topic in the United States, other countries are also looking at entering the game, especially in Europe, where natural gas supplies from Russia were cut this winter over pricing disputes. “We definitely see European companies showing a strong interest in learning more about producing natural gas from shale,” said Ed Smith, vice president of technology for BJ Services.

BJ’s Understand the Reservoir First philosophy, which has been in place for more than 10 years, is being deployed in shale-gas reservoirs to understand everything from the mineralogy to geo-mechanical properties.

“We need to understand what types of proppants, fluids and technologies make sense for a particular reservoir so we can help the operator to economically extract the most gas,” said Randy LaFollette, manager of shale technology, BJ Services. “Operationally, our emphasis is on making sure we’re staying ahead of the curve on the reservoir-specific technologies required for each of these plays, and what each well needs to be more prolific.

“If we’re dealing with a shallow, low-pressured formation that is soft, we might use the VaporFrac system, a high-quality foam based on a surfactant gel system that puts minimum water on the formation,” he continued. “This is run in combination with an ultra-light weight proppant that’s easy to transport into the fracture.” Alternatively, the Marcellus is often fractured with slickwater and a mix of 40/70 white and 100-mesh sand. “But it depends on the rock properties,” Mr LaFollette said.

In the harsher environment of the Haynesville, which requires high injection pressure to fracture the reservoir, either slickwater or crosslinked gel are utilized, he explained. “Here, we typically recommend intermediate-density ceramic proppants with the strength to better resist fracture closure at the end of the job and during the producing life of the well.”

The Eagle Ford is currently pumping the largest proppants of any of the shale plays in order to keep this softer rock open, Mr LaFollette noted. The larger proppants are less susceptible to embedment.

“To optimize well performance, there is a need to integrate wireline logging with well architecture and hydraulic fracturing, and to validate what we’re doing with microseismic monitoring and possibly other monitoring methods,” he continued.

The IntelliFrac service, which combines Baker Hughes’ microseismic technology with BJ’s fracturing technology, was recently introduced, Mr LaFollette said. “We are seeing more efficiencies that are helping us understand much earlier what the key challenges are in a particular play, and applying the right tools and technologies so we don’t have to do a lot of cut and try.”

ZoneSelect is a trademark of Weatherford International. Reservoir First, VaporFrac and are trademarks of BJ Services. IntelliFrac is a trademark of Baker Hughes and BJ Services.

I would like to thank you for this information and would know more about drilling operation

I would like to thank you for this information and would know more about operation

i like bj is my famel