Advances in simulators support industry’s shift to blended learning

As more companies look to virtual and hybrid well control training, industry works to improve software accuracy, expand their flexibility of use

By Stephen Forrester, Contributor

Drilling simulators have provided the oil and gas industry with a means of performing engaging, hands-on well control training for years. While many might associate “simulator” with immersive training with cyber chairs, other types of simulator-based training – both virtual and blended – have accelerated significantly, driven by both advancements in cloud computing and the challenges of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, companies recognize there remain critical advantages to in-person courses at large training centers. Better software with more accurate modeling, a greater amount of user choices and flexibility in course delivery will be key for well control training in transition.

Normalizing a hybrid learning model

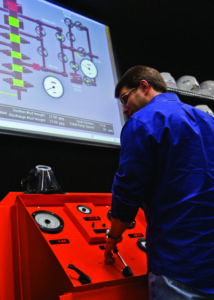

Simulators used for well control training have progressed significantly in recent years, going from systems with comparatively rudimentary graphical capabilities to today’s immersive 3D environments. These changes have been enabled by advances in processing power and virtual reality/augmented reality technologies. Simulators now range in size from portable devices that can be plugged into a laptop to what the industry calls “full mission” simulators. The latter have multiple cyber chairs in dedicated rooms with full video walls, designed to create an experience where trainees feel like they are in an actual operating environment.

The goal of these immersive simulators is to train students to respond to events as they happen in a sequence, recognizing that a well control event is often the culmination of many smaller errors or problems. The human factors element cannot be truly replicated in any other way, said Clive Battisby, Drilling Systems COO. Immersive training, he believes, is the most effective option to improve crew resource management, information sharing and knowledge transfer, and establishing the right communication flow between crews. This is why Drilling Systems continues to push the design and development of such simulators.

However, there’s also been a shift in focus to cloud-based software over the past year. With well control training accrediting bodies like IADC accommodating virtual course delivery, Drilling Systems responded by moving its training into the cloud.

Drilling Systems’ virtual training software is platform agnostic, so it can be implemented by any organization regardless of what form of videoconferencing it uses. Additionally, moving to the cloud removes hardware-specific processing limitations.

Last year, in response to the pandemic, Drilling Systems adapted its well control training software for use by Louisiana State University (LSU), with the university creating virtual classrooms where students could develop and fine-tune well control skills remotely, overseen by an instructor.

This cloud-based well control software, iDrillSIM, was then launched after successful trials at LSU and has been implemented by several offshore drilling contractors. Valaris, for example, began using the software in mid-2020 and has since delivered IADC WellSharp Supervisor and Driller Level courses to more than 400 crew members across 28 countries. “Delivering virtual simulator training with the iDrillSIM has been invaluable during the pandemic,” Eliot Doyle, Valaris Senior Training and Competency Manager, stated in a May 2021 news release. “It has helped us to continue educating our workforce regardless of where they are in the world – ensuring competency and compliance.”

Noble is also using the iDrillSIM simulator software for virtual well control training. It allows the company to create scenarios for complex wells with significant operational challenges, such as kicks or losses in a horizontal well or kicks during the well completion phase. “We were surprised and pleased with the amount we were able to get through without physically bringing our teams into our NobleAdvances training facility,” Noble instructor Chris McGehee said. “As well as allowing us to look at specific problems in detail, the process brought up potential issues, which we were able to review and address before going into the field.”

Moving to the cloud, however, comes with its own set of challenges, including latency and bandwidth concerns across time zones and in remote locations, as well as cultural issues like “Zoom fatigue.” Although many organizations and individuals are starting to come out from under the shadow of COVID-19, Mr Battisby believes that remote training options will remain relevant, particularly when cost effectiveness is considered. Additionally, he cited an IWCF statistical study indicating there is little variance in the scores achieved on well control certifications between those who attended in-person trainings and those who attended online courses.

Still, Mr Battisby said he believes there cannot be a true replacement for face-to-face courses that take place within immersive simulators. “When it comes to learning methodology – how an instructor delivers a course – remote and in-person courses are very different. With remote training, you won’t get the same engagement, and certainly the instructors need additional coaching for remote course delivery. If you’re an instructor with 12 people in a virtual class, how do you pick up on the fact that someone is struggling? How do you communicate as effectively?”

Valaris and Noble have said they intend to use both remote and in-person training moving forward, a hybrid model that Mr Battisby thinks will be more of the norm in the future. “There will be a blended approach to the learning journey,” he explained. “Virtual well control training is good for knowledge delivery – for example, mandatory or regulatory trainings – but around that, you still have high-value courses that are best delivered in person.”

To facilitate and streamline the delivery of face-to-face courses, Drilling Systems has also been offering for the past few years an On-the-Rig (OTR) simulator. “By deploying a very small simulator to a rig, we allow them to do what we call ‘drill the well on the simulator,’” Mr Battisby said. “We’re providing well-specific, well-control-related and drilling-activity-related training programs, and the knowledge that we want to pass on to the crew, at the point of delivery.” If an operator knows that it will be drilling a certain type of well, a pre-well simulator course can provide a virtual roadmap of possibilities for the upcoming project.

In late 2020, Wellesley Petroleum rolled out the OTR to the Borgland Dolphin semisubmersible for a challenging well in the Norwegian North Sea. Because the well involved potential shallow gas concerns, drillers expected to have far less reaction time to deal with well control issues. By modeling well-specific conditions and drilling scenarios based on the drilling program, the crew used the simulator to better understand the well and possible well control events before the rig left the quayside. Ultimately, the training and well preparation work helped the crew deliver their lowest-cost well for 2020 while achieving excellent safety performance, according to Callum Smyth, Operations Manager at Wellesley Petroleum.

When it comes to the software engine and the well model itself, Mr Battisby said that Drilling Systems has created an application programing interface that opens its software platform to scientists and other qualified individuals in academia and at operating companies so they can modify/update their own dynamic models. This will allow the simulator to access complex and advanced engineering modeling.

Developing the most accurate simulation

Endeavor Technologies believes that software and accessibility are critical to the future of drilling simulators, especially those used in well control training. The company developed a simulation model that aims to achieve what CEO Brad Reiser called “accuracy so close to reality that the simulation and the real world effectively overlap.” This priority, he said, is what sets the company apart.

“We’re constantly adding more code,” Mr Reiser said. “As part of our continuous improvement strategy with product development, we add about 10,000 lines of code per month.” Most of the new code goes into the company’s software engine to increase the amount of data it can process per second. On average, the engine can now process approximately 1,000 equations, four times per second, according to the company.

The hydraulics model, Mr Reiser explained, has been run alongside real-time rig data and proven to achieve 98.9% accuracy. The company aims to get as close to 100% accuracy as possible so that the simulations can provide a very accurate approximation of what’s happening out in the field. Endeavor believes this accuracy is its differentiator and is critical to improving safety and efficiency for the industry, especially for those who are drilling risk-heavy, highly complex wells. “Operators value the model accuracy and the freedom and flexibility to do things with it that they couldn’t do otherwise,” he said. On the other hand, some customers give less priority to model accuracy, instead focusing on establishing a sequence of events for the decision-making protocol.

The software framework is malleable – it can be delivered online or on a physical simulator, whether on a rig or in a training center. It also allows flexibility in the presentation of different types of well geometries, fluids and gases, as well as how these components interact with each other. Everything is modeled in 3D, including gravity and component movement – with solids settling and gases floating up – so the simulator can visualize fluid paths and migration exactly as they would occur in the field. While it would be impossible to predict all use cases, Mr Reiser said, the nature of the software infrastructure means it can be adapted to a virtually limitless number of scenarios.

Endeavor works closely with its customers, as well as industry associations like IADC through its KREW and WellSharp Live programs, to continuously improve the model to meet industry training needs. The company also builds out 3D flow models in its simulators that can be used with various training scenarios based on specific well profiles, equipment suites or operating conditions. This makes it scalable, because if downhole conditions are comparable in a particular field or on a certain campaign, everyone involved can train on a model that closely matches what they expect to encounter.

In one project, Endeavor helped to re-create a significant well control event that a company had experienced several years ago, simply by importing data from that specific well into the simulator.

An online training exercise was built around this simulation, which the customer was able to easily push out to its employees around the world. This allowed everyone in that functional discipline to run through the simulation to ensure understanding of what happened and how to avoid it in the future. Employees who could not pass the simulation could not operate equipment again until they did. “As a result, they haven’t had a similar event since then,” Mr Reiser said.

While the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is accelerating remote learning of this type, he believes in-person learning will remain relevant, as will large drilling simulators with cyber chairs positioned behind expansive video walls. “You can’t replace the nuances of training in a face-to-face environment. You have to account for all the ambient conditions, learning styles and body language.”

On the other hand, Mr Reiser said he also sees an ongoing transition to more portable simulator technologies. Endeavor’s simulations can be housed on a USB device that plugs into a laptop and runs from the cloud. This eliminates bulkier components and simplifies transport and setup. While this type of training will not provide the user with the immersive experience of sitting in a cyber chair, Mr Reiser said that in scenarios where accessibility is crucial – on a rig, for example, for pre-job safety meetings – KPIs usually involve improving decision making and muscle memory, not immersivity.

A training provider’s perspective

At Wild Well Control, simulators help to teach trainees how to respond to possible well control events within a simulated rig environment, according to International Operations Manager for Well Control Training Josh Thiel. “Primarily, that’s what simulators are used for: recognizing kicks entering the wellbore and having drillers respond to that,” he said. “They’ll see the warning signs, and that helps them practice shut-in procedures and, once the gas is there, how to deal with it.” In supervisor-level courses, the focus shifts to dealing with gas; simulators allow them to practice things like different circulating methods.

Wild Well Control is also using simulators for more technical education, modeling gas behavior and gas migration and how they affect pressure. What was once mapped out on a white board with drawings and calculations can now be done with extreme accuracy in a simulator room. “We can put a gas bubble in the well and tell the driller to open the choke and keep the casing pressure constant and ask, what’s happening in your well? Are you maintaining constant bottomhole pressure?” Mr Thiel explained. “They can see the mistakes they make or how something they think is controlling pressure isn’t. We can use it to teach and reinforce the actual skills they’ll use out on the rig.”

The future of well control training, he added, will be simulators that can deliver an experience that matches the real world as closely as possible. “From a training provider’s standpoint, functionality is the biggest thing. We want the most realistic environment for the student to learn in, and providing the most accurate depiction of what they will see when they’re in the field is critical.”

The acceleration of virtual learning and remote coursework due to the pandemic, he noted, has changed the way the industry looks at simulator training. The logistical advantages are obvious. In one recent course, for example, a well control instructor delivered courses in various regions globally without the need for travel and related expenses. However, he echoed others’ sentiments that online courses cannot account for the same level of engagement as their in-person counterparts.

In many instances, tactile elements and immersivity make a real difference for the learner, Mr Thiel said. And from the instructor’s perspective, face-to-face interaction provides nonverbal cues and other signs the learner is struggling, which can get lost on a Zoom call. “As an instructor, we like to be there, to really get in and help,” Mr Thiel said. “If a student is struggling with operating the choke, we can walk them through how to deal with their problems. You lose a little of that with remote learning.” DC