North Sea pilot shows potential for interoperability between different automation systems

‘Orchestration’ system allowed communication among various components, rig control system to ensure advisory outputs do not conflict

By Stephen Whitfield, Senior Editor

Drilling automation has seen significant progress over the past few years, enabling companies to focus on dynamic adjustments of parameters to respond to downhole conditions in real time. However, achieving closed-loop drilling automation – an automated system that can self-monitor and assess potential issues, as well as take steps to mitigate those issues – will require an amalgamation of well engineering and well delivery solutions.

Integrating these components into one system poses a number of challenges, namely in the communication between each component and the driller, particularly when the components are developed by different third-party OEMs and running on different coding structures.

Real-time advisory systems typically receive high-frequency and low-latency data to run simulations in their digital twin systems, providing discrete advice based on vibration, well placement, hole cleaning and pressure management. The recommendations provided by these advisors can have conflicting objectives – for example, a vibration advisor may recommend decreasing RPM to mitigate bit bounce, but at the same time ROP may need to be increased to achieve a target ROP. The orchestration of these discrete drilling parameters is required to produce a unified set of advisory outputs.

“Sometimes, when you have different digital twins of systems working at once, you can get a lot of conflicting advice from those systems, and you have to orchestrate that. If you don’t orchestrate it, you will have a very confused driller,” said Oddbjørn Kvammen, Integrated Real Time Operations and Consulting Manager at Halliburton.

At the 2025 SPE/IADC International Drilling Conference in Stavanger, Norway, Mr Kvammen outlined the development of an automated orchestration system from Halliburton, as well as how it was used on a rig in the Norwegian North Sea to integrate the automation systems from a second service provider into the rig’s control system.

Those automation systems included bottomhole assembly (BHA) and trajectory automation, as well as hydraulics performance automation. The systems also utilized an OPC-UA (open platform communications unified architecture) server and included various modules for data exchange.

Effectively, the orchestration system, when combined with the automation systems, creates a common platform where independent advisory systems from different vendors and disciplines can coexist. Further, open composite advice can be produced in real time by integrating the recommendations from the different systems. The automated execution of processes within this integrated system, he said, enables more informed decision making on the rig and minimizes operational errors.

The key objective for the combined system was to develop unified workflows for both surface and downhole automation components. These workflows, Mr Kvammen said, would minimize variability and improve the predictability of the automation: “Basically, we wanted to show that we could do on-bottom drilling, one stand at a time, while effectively orchestrating the things that automate the on-bottom drilling together with our collaborators’ systems, including the rig control system. This requires a lot of interoperability.”

The system is an orchestrator that provides a scalable framework to integrate multiple independent and sometimes conflicting recommendations related to separate aspects of drilling.

The orchestration is driven by the interdependence between ROP optimization, hole cleaning and stability, geopressure limits, bit and BHA mechanical limits, buckling limits, vibration mitigation and steering requirements. These set points and limits are then delivered to the rig through a custom interface incorporated into the automated drilling control system.

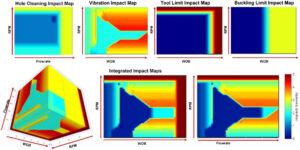

The orchestrator is installed on an edge computing device on the rig and provides set points for flow, RPM, WOB and ROP to the rig’s control system. It constructs impact maps in real time – an impact map is a visual representation of the relationship between the drilling parameters and the relative consequence on drilling operations – using data from each independent advisor and combining them to define integrated recommendations in the space of the drilling parameters.

These impact maps are then further combined into a single map that outlines the safe operating zone for various drilling parameters. For instance, a hole-cleaning map may illustrate the potential impact if the current drilling RPM and flowrate is below, equal to or above the recommended RPM and flowrate. A vibration map displays the recommended range for RPM and WOB to mitigate a particular vibration. A tool limit impact map would show the safe operating zone for RPM and WOB per the tool specs.

In creating an integrated map showing all of these potential impacts, the orchestrator can recommend to the driller which parameters need to be met in order to ensure safe operations for all of these components at once.

The driller is then able to see, at the same time, the various impact that a certain RPM or ROP would have on multiple functions. If the system determines that a parameter is approaching the boundary of safe operation, it will alert the driller. The driller can then input, if needed, which operating parameters should be prioritized. The orchestrator would communicate with the rig’s control system to take automatic mitigating actions should those parameters fall outside the safe operating envelope.

“We can look at this information, and then we can communicate which movement should be the most important one for the orchestrator, depending on what we are doing on the rig. We can also change this on the rig as we see what’s happening,” Mr Kvammen said.

The orchestrator was installed on a rig offshore Norway last summer and tested over the course of two wells, which were completed in July 2024. The design stage of the installation involved validating parameters and configuring them within each automated component. During well execution, the system supported real-time orchestration and automation, with remote operators verifying each decision made by the system.

The test covered the operation of the orchestrator in three phases:

A shadow mode where the driller was not made aware of the recommendations provided by the orchestrator, but the stability and relevance of the recommendations were still tested;

An advisory mode where the driller needed to approve any parameter changes before actuation; and

An active mode where the recommendations were sent directly to the rig’s control system within a management-by-exception framework. In this mode, the driller could take back control of the system at any time.

The pilot project was conducted during the 8½-in. and 6-in. sections of each well. Both service companies installed and commissioned equipment at the rig site to enable secure connectivity between their solutions and digital transfer of the operational limits between themselves and to the rig control system.

Halliburton and its partners observed a consistent exchange of information between each automated component and the orchestrator throughout each drilling section.

An additional pilot on the orchestration system with a separate operator is scheduled to take place next year.

“I think we have proven with this pilot that the interoperability between the different companies involved is possible,” Mr Kvammen said. “I’m not saying that we are done. I would say that we’re just scratching the surface. There are still a lot of things to do when it comes to autonomous drilling, but I think we are on the right journey. We have proven that we can easily communicate between different parties, exchanging data between the different vendors. That was very effective.” DC