Innovative power system setups aim to help more rigs access, run on grids

Using grid power instead of diesel generators can reduce emissions, but grid constraints, permitting complexity and cost remain barriers

By Stephen Whitfield, Senior Editor

The drive toward decarbonization and operational efficiency is catalyzing a shift in rig power systems. For drilling contractors, this shift can be seen through their increasing application of technologies that reduce the rigs’ reliance on conventional diesel generators. In the US in particular, where large-scale drilling programs and evolving emissions regulations intersect, rig electrification presents a major opportunity for innovation.

Although many of these alternative rig power systems have been around for a while, it remains a challenge to scale them to a level that provides both significant emissions and cost savings. Regional grid constraints, infrastructural incompatibility, complexity of the permitting process and total cost of ownership are among the hurdles that still need to be overcome. Creating strategic partnerships among operators, drillers, OEMs and utility providers will be critical to clearing those hurdles.

“All of the stakeholders – the drillers, the operators, the utilities – see the challenges and risks with electrification, but they also see the potential benefits and the wins,” said Rami Barqouni, Power Management and Controls Global Product Manager at Canrig Drilling Technologies. “If we’re going to capitalize on these benefits, the utility grids need to invest more into building the capacity for delivering power, and the operators should be willing to communicate with the utility grids on their drilling plans and – at the same time – provide incentive to drilling contractors to electrify the rigs.”

The ability to power a rig primarily off of an electric utility grid has largely been limited to rigs located near existing utility infrastructure, typically in urban areas. Even then, the industry recognizes that some utility grids are not set up to guarantee sufficient capacity to meet the rig’s power demand at all times. If the utility cannot guarantee sufficient power, operators may not choose to use utility power at all because it may not be practical to switch to diesel generators during operations. Switching might mean the rig would need to completely power down – yet powering down even for a couple of minutes could create well control issues.

In 2023, Patterson-UTI took a major step to improve the accessibility of grid power for land rigs by combining EcoCell, the company’s battery energy storage system (BESS), with GridAssist, its proprietary utility transition skid, on a rig in the Permian Basin. The system effectively created a low-carbon backup to supplement grid power, making grid power a more attractive option for operators.

“We’ve been electrifying drilling rigs for years,” said Marcel Snijder, Senior Manager – Power Systems Product Development at Patterson-UTI. “But what we’re finding with utility power is that the grids are more stressed than they’ve ever been. It can be hard to get the utilities to allocate to drilling rigs the amount of power we need for our projects.” That challenge can be sidestepped by lowering the peak power usage and enabling a more consistent power draw from the grid, he said.

Nuclear power is also gaining some interest in offshore settings because of its low emissions and power density – one uranium fuel pellet can create as much energy as 149 gallons of oil or 17,000 cu ft of natural gas, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute. Nuclear propulsion has been used for decades by various state-owned cargo ships and icebreakers, but commercial use, like on a drilling rig, has yet to be realized.

Lloyd’s Register is working with energy industry stakeholders to forge a pathway for adopting nuclear reactors in a commercial marine application – and the organization sees that pathway potentially becoming reality within the next 15 years. To do that – particularly at scale – the industry still must flesh out issues around regulatory controls and the technical infrastructure. Among other things, the development of adequate disposal infrastructure for nuclear waste is needed, along with the creation of standards around nuclear reactor design.

“The regulators want standardization more than anything else,” Peter Wallace, Principal Engineer – Risk and Regulatory Advisory at Lloyd’s Register, said, noting that marine industry OEMs are already exploring standardized ways to build multiple copies of a reactor. “I don’t think we can do nuclear at scale without standardization. It takes too long to qualify and license a single reactor unit and its associated systems.”

Connecting the grid to battery storage systems

Power from the utility grid is less carbon-intensive than traditional wellsite power generation and offers additional benefits like cost savings and noise reduction. Many permanent facilities, such as compression stations and producing wells, now operate primarily on grid power, often with a renewable energy component.

With drilling rigs, however, only a relatively small percentage have strayed from traditional diesel power despite the potential benefits. One reason is that, as fields get more developed, it can become increasingly difficult to access adequate power capacity for temporary facilities with variable demand, such as drilling rigs. This is because power demand from an oil and gas field tends to increase as producing wells come online and additional pipelines are constructed, yet utilities tend to prioritize supplying power to semi-permanent facilities over mobile facilities like a rig.

On top of that, the lack of sufficient capacity in most utility grids acts as another barrier for widespread adoption of grid power for drilling. Underinvestment and inadequate forecasting by utility providers have left many grids struggling to meet the growing requirements of drilling and other industrial uses, such as manufacturing, electric vehicles and data centers.

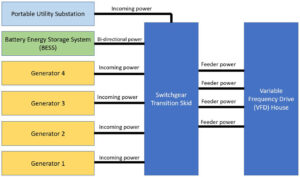

By using the EcoCell and GridAssist technologies in conjunction with each other, Patterson-UTI was able to overcome those challenges. This integrated application required additional custom hardware – a portable substation and the GridAssist transition skid – that interconnect the batteries with both the utility grid and diesel generators on the rig. This setup restricts the power drawn from the utility to stay within predefined requirements – typically the limit is set by the utility once per rig move, following a request submitted by the operator. The setup also enables peak shaving, by drawing power from the battery storage and, if necessary, the diesel generators.

This effectively creates a new chain of command for the energy used on the rig. The utility grid is the primary source of rig power, instead of the diesel generator. If the grid cannot provide sufficient power due to supply interruptions or other factors, or if the rig needs more power than the limit given by the utility, additional energy from the battery serves as a supplement. Then, if those two power sources are still not enough, the diesel generators come online.

This system effectively reverses the chain of command from what would typically be seen with a BESS – instead of the battery getting charged by excess power burned off the generator, it’s getting that power from the grid.

“The GridAssist is enabling us to limit the utility power to any amount. We might go from one pad that has plenty of utility power to another pad that has only a megawatt or two,” Mr Snijder said. On top of that, he added, “the demand from the rig is extremely variable. When you’re hoisting, you’re all of a sudden consuming several megawatts of power. When you stop, you’re consuming a very low amount of power. Whenever our demand is below what the utility can provide, we can run entirely off the utility and charge the batteries using whatever additional utility power we have. When the power demand rises above what the utility can provide, we have other sources.”

The portable substation within GridAssist is needed to step the line voltage down from the power coming from the utility before it goes into the transition skid. The skid is positioned between the generators, the battery and the variable frequency drive (VFD) house, which controls the speeds and power output of electric motors used in various components like the mud pumps, drawworks and top drives.

Mr Snijder said the GridAssist skid was necessary due to limited space in the VFD house, which was originally designed for just the diesel generators. Patterson-UTI needed an additional component to house the switchgears that would connect the utility to the battery and generators.

“We’ve done some creative things over the years to fit more stuff inside that VFD house, but after a while you hit a real estate limit,” he said. “You cannot keep your generator breakers that you usually have in there, and then add a 5,000-amp utility breaker, another breaker for the battery, and all the controls and filters that go along with that. Packaging everything on a separate skid is essential. You need space for this, but we’ve seen that the pad constraints are not so stringent that they can’t accommodate an additional skid.”

Mr Snijder also emphasized the importance of the system’s automation functionalities in order to avoid adding to the driller’s workload. Signals from the power feeder cubicles for the generator and the battery are routed to the rig’s automation system and the control system. The driller’s interface was updated to display data from the new power system, and all but one process – setting the limit for power taken from the utility – is automated.

“Everything that’s required to maintain enough power supply for the rig is automated: The amount of power that the battery draws to charge or discharge is automated. The system is automatically starting and stopping generators and controlling the load on these generators. If you have a situation where the power demand increases, the battery is supplying that additional power. All of this stuff is going on in the background to where the driller doesn’t need to pay attention to it. The driller is just controlling his tools, drawworks and mud pumps. He can have faith that there is going to be enough power available for those operations,” Mr Snijder said.

The integrated application of the EcoCell and GridAssist technologies was first tested at Patterson-UTI’s construction and test facility in Houston in 2022 before being deployed on a land rig in New Mexico the following year. The initial deployment showed the rig was able to operate smoothly across a range of utility power draws (between 0.5 MW and 4 MW) taken from the various locations where the rig operated over the course of the year.

For instance, during a tripping operation in which the rig was pulling out of hole at approximately 16,000 ft, the high power demand from the drawworks exceeded the power that the utility could supply. As the driller began hoisting, additional power was discharged from the BESS, creating a buffer between the actual utility consumption and the limit. During intervals between stands, the BESS recharged slowly as the blocks were lowered, replenishing the energy used while hoisting. Overall, with the utility limit set to 1.5 MW, the rig completed 87% of operations without having to rely on diesel generators.

In most locations, approximately 2 MW of utility power was available for the New Mexico rig during testing. Under these conditions, the rig was able to complete 98% of operations without relying on generators.

As of July 2025, the EcoCell/GridAssist combo is running on two rigs in New Mexico. Mr Snijder said that Patterson-UTI is having conversations with operators about expanding the system’s application, both within the Permian and beyond.

“There are a lot of opportunities out there,” he explained. “It really just comes down to having scenarios where you have utility power available, but not always enough utility power to power the rig. When you look at various regions where a lot of drilling is going on – Appalachia, the Rockies, different parts of Texas – that’s where we’re having some discussions.”

Scaling rig electrification

While the concept of powering land rigs from the utility grid has existed for over a decade, it remains relatively uncommon, especially in remote oilfields where infrastructure, permitting and reliability are significant barriers.

There are no official statistics tracking the number of rigs connected to a utility grid in the Lower 48. However, Carolina Stopkoski, Senior Product Line Manager – Energy Transition at Canrig Drilling Technologies, estimated that only about 20-25% of operating rigs are connected to highline power. Scaling grid-powered rigs, she said, will require an ecosystem that better incentivizes both the operator and the drilling contractor.

“As a contractor and as a technology provider, we carry the cost of the equipment needed to electrify a rig and the costs of integrating that equipment into our existing technologies,” she explained. “However, the operator carries the cost of planning, the costs of sourcing the power and engaging with the utility to tell them where they’re operating and how much power they will need. The costs to deliver electricity are better today than they were 10 years ago, but it can still be expensive. We can only scale this if we can make this cost effective.”

For Canrig, a subsidiary of Nabors Industries, ensuring cost certainty is a key priority in developing that ecosystem. The process of planning for an electrical power installation remains slow and difficult, Mr Barqouni said, which ends up discouraging widespread investment in the technologies designed to enable grid-powered rigs. While the planning process varies between jurisdictions, typically operators will choose a pad that they want to electrify, then approach the utility provider with its plans to drill on the pad and request for a certain amount of power to be delivered.

Processing that request can take a long time to complete – Mr Barqouni said it could take between 8 months and 14 months, depending on the utility and appropriate regulatory body. These regulators include such entities as the Texas Railroad Commission, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), and other utility companies and regional governmental regulators depending on the municipality, wherever the operator wants to electrify the rig.

Extrapolating that time on a pad-to-pad basis can make it difficult to scale to a full field development in a time-efficient manner, especially if a field has 10 or 20 pads, since the power request for each pad has to be processed separately. Mr Barqouni noted the importance of operators and drillers working with US state regulatory agencies and utility providers to streamline that permitting process.

Some utilities in the US do offer multi-pad, or corridor-based, infrastructure applications for pads in the same field, he added. However, this depends heavily on the utility company, the state where the application is being filed, and the scale of the operator’s development plan. Allowing multi-pad applications for pads in different fields is rare.

“Imagine if, instead of applying pad by pad, you could apply for a whole field, or the operator can do one request for a number of pads at the same time that aren’t necessarily in the same field. That could lead to a more planned approach where everything is done at once, because we know sooner that we will be using electricity in those certain areas in the future. The drilling contractors can then invest in adding electrification units to their rigs, instead of having it as an add-on third-party service,” he said.

Electrification units include technologies like the PowerTAP transformer module from Canrig, first deployed in 2022. The system modifies incoming highline power voltage, aligning it with the rig voltage and integrating the utility grid with the rig’s powerhouse. The module is positioned next to the rig’s powerhouse and connected to highline power, with a medium-voltage, reel-fed cable that sits next to the utility pole.

Systems like PowerTAP are typically needed for rigs running on a utility grid as it allows the rig to switch between highline and generator power. Rig moves may require a switch to just generator power to account for timing or utility company service activation or deactivation. Disruptions in electrical utility service, or an operation where the power demand exceeds the supply provided by the utility, may also necessitate generator power.

Drilling contractors need an incentive to spend the money to retrofit their rigs with systems like PowerTAP, in part because of the sporadic nature of approvals for utility power. If operators have the means to get approval for a full field development within one permit, that could incentivize drilling contractors to make the investment in more retrofits, Ms Stopkoski said.

“The incentives are different between an operator and a drilling contractor. The operator has a clear incentive – they’re seeing the true net savings on a daily basis because they’re saving on diesel costs. The drilling contractor also has an incentive – they’re not using certain equipment as frequently, so they’re saving on maintenance – but that’s not something you see every day,” she said. “If the operator is only contracting you for a couple of pads here and there, that benefit is small and does not help improve scalability.”

Standardizing regulatory requirements is also necessary to enable scaling. For instance, the way a utility requires drillers to connect their rigs to the grid varies from region to region. Some jurisdictions require drillers to connect the transformer module to a metering cabinet, which measures the amount of electricity transmitting to the transformer, while others do not. Some jurisdictions require the installation of visual disconnect devices like load-break utility disconnect switches, while others do not.

Ms Stopkoski noted the difficulty in standardizing these requirements given the byzantine nature of jurisdictions in the US – different utilities have different priorities – but efforts to standardize would go a long way to scaling electrification.

“When you look at a rig, it’s portable in nature. We’re moving these things from remote location to remote location, and they’re meant to be their own power plants,” she said. “Once you get into the regulation of connecting directly to the grid, the challenge lies in the differing interpretations and requirements of electrical codes and utility standards across jurisdictions, which complicates compliance planning for portable rigs. Standardizing would be very helpful, because then it would make the cost of integrating a unit known right away. If you have the utility giving out all of these different requirements that take you outside of maximizing your return on investment, the incentive is gone.”

Nuclear power on an offshore rig?

The scale of the challenge in decarbonizing E&P operations has put all options on the table, including nuclear power. Advanced nuclear technology is being developed that could be suitable for safe deployment on a new generation of marine vessels, including drilling rigs, Mr Wallace of Lloyd’s Register said. In fact, it could become a viable option for offshore oil and gas in the near-term future, he added, predicting that nuclear reactors could become a realistic option for powering an offshore rig by 2040.

“Nuclear power will be funded and organized,” he said. “I think you will have a handful of early adopters. It’s like any new technology. With battery energy storage, it was an esoteric thing back in 2012, but by 2015, after that first wave of adoption, if you weren’t looking at batteries in certain marine communities, you weren’t being taken seriously. Once we get that first wave of adopters, or even the second wave of adopters, that’s when something like nuclear could become off-the-shelf.”

The benefits of nuclear power for offshore industries are clear, Mr Wallace said, particularly its high energy density compared with the conventional fossil fuels used to power generators. This higher energy density means that offshore platforms could operate for extended periods without the need to refuel.

“One of the things with nuclear is that, all of a sudden, the fuel discussion disappears. The turbo machinery can run for years. A nuclear gas turbine can run between five and seven years without turning off,” he said at the IADC Drilling Engineers Committee’s Q2 Tech Forum on 1 July, where he presented on the feasibility of nuclear power in drilling.

Despite his optimism, Mr Wallace acknowledged there are several steps – both technical and regulatory – that still need to be taken before the industry can see nuclear reactors on rigs.

On the technical side, the challenge involves building up the readiness levels of the available reactor technologies. There are three potential reactor types to consider, he said.

The first type, micro-reactors, is a nuclear heat pipe used as a passive heat transfer device. Uranium is used as a fuel to generate heat through a controlled nuclear fission chain reaction in the reactor core. That heat is then transferred to a working fluid in the micro-reactor and can be used for conversion to electrical power.

The second type of reactor, a molten salt reactor, uses uranium dissolved in a molten fluoride salt liquid mixture to generate heat. The molten salt acts as a coolant and a moderator, sustaining the chain reaction. Heat is then transferred to a working fluid, which can be converted into electrical power.

The third type, a pressurized water reactor, uses uranium as a fuel to generate heat. That heat is then transferred to a coolant, typically water. The heated coolant remains in a liquid state at high temperatures due to the high pressure maintained within the reactor vessel. This heat can then be turned into electric power.

The type of reactor best suited for a given marine application, like offshore drilling, would depend on stakeholder preference, Mr Wallace said. Different considerations include the cost of installing a given reactor type on an offshore installation, the ease of building the reactor, and the size of the reactor needed to produce a given amount of electrical power. The answers to those questions will become clearer as the technologies get further developed, he noted.

The challenge, regardless of reactor type, is not necessarily in developing the reactor itself. For example, the industry will need to look at developing the fuel needed to power the reactor. If industrial sectors like oil and gas adopt nuclear reactors, increased demand will call for increased mining of the necessary uranium.

Handling of the uranium and, perhaps more importantly, handling of the waste, pose additional challenges. Disposal of radioactive waste requires secure and sustainable solutions to prevent environmental contamination. Nuclear reactors create waste streams just as internal combustion engines and batteries create waste streams. However, the waste generated by nuclear reactors is unique in that it is small in volume and well contained, and its radioactivity can be precisely measured. This allows for more controlled handling and disposal compared with waste from other technologies.

Several regulatory guidelines already exist for the disposal of nuclear waste. The International Atomic Energy Agency has established safety standards for the disposal of radioactive waste, which are adhered to by member countries to ensure the protection of human health and the environment. EU Directive 2011/70/Euratom established a community framework for the responsible and safe management of spent fuel and radioactive waste. In the US, radioactive waste is regulated by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission and state agencies.

However, Mr Wallace said the construction of sufficient disposal infrastructure to meet growing demand for storage is still lacking, although the EU has several ongoing projects to try and change this.

Finland, for instance, is set to become the first country with a permanent, deep geological repository for spent nuclear fuel at its Onkalo facility. Set to open either late this year or early 2026, it will store highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel in watertight canisters, deposited into bedrock more than 400 m deep. The canisters will be isolated and kept underground for 100,000 years.

Andra, France’s national agency for the management of radioactive waste, expects to begin construction on its Cigéo deep geological disposal facility in 2027; highly radioactive waste will be stored at a 500-m depth.

These future European sites will be licensed for the disposal of spent nuclear fuel waste from civil reactors, such as the ones that would be used in a commercial marine application like offshore drilling.

The US has the world’s only deep geological disposal site that’s currently accepting nuclear waste of any kind – the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico. However, it only stores defense-related transuranic waste, or waste contaminated from nuclear elements heavier than uranium. Transuranic waste is typically a byproduct of nuclear weapon production and related activities, while spent nuclear fuel is typically generated by nuclear reactors.

According to the US Government Accountability Office, the US has more than 90,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel from commercial nuclear power plants. The US government has yet to build a permanent geologic repository for this waste, however. As a result, the amount of spent nuclear fuel stored at nuclear plants in the country is growing by about 2,000 metric tons per year. So far, plans to build a commercial-use site in the US – at the proposed Yucca Mountain repository in Nevada – have been stifled by state and federal opposition.

Mr Wallace said it will be critical to build out such infrastructure for long-term disposal of nuclear waste, if nuclear power is to become a reality in offshore drilling.

“If small nuclear reactors take off, there will be nuclear fuel and there will be waste that needs to be handled. The EU has determined that this is a major issue over time, and several countries are already progressing in building facilities, or have several that are in certain stages of licensing. The US marketplace isn’t there right now. You have to have your disposal and decommissioning plan put together before you even get your license.”

Lloyd’s Register is currently working with energy industry stakeholders to build a comprehensive assessment of both nuclear fuel production and supply, as well as the reactor technologies under development for onboard power generation.

One such project Mr Wallace mentioned is a collaboration with Prodigy Clean Energy that aims to complete the development of lifecycle requirements for Prodigy’s transportable nuclear power plants (TNPPs). First announced in March 2025, the project will produce models for TNPP marine fabrication, marine transport and centralized decommissioning. Plans call for deployment of the TNPPs in Canada by 2030.

The two entities expect the project to demonstrate how a country can manufacture, deploy, operate and decommission transportable and floating nuclear power plant technologies without making major changes to sovereign regulatory frameworks.

Prodigy is working with a multinational mining company for its first TNPP project, aiming to supply power to a large remote critical minerals cluster in Canada. Feasibility studies are under way, which include gathering site and environmental data, performing a prototypical test program, and engaging with local indigenous communities. DC