To ensure a procedure is effective, human performance must be considered in its development and management

Procedures must account for the nature of work on a job site, build in flexibility and avoid unnecessary complexities, says Shell Human Factors Lead

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

On the surface, procedures seem like very simple things. It’s about “writing down how to do something when we do it that way,” said David Jamieson, Human Factors Lead at Shell. “When you say it like that, it seems really simple, and you wonder why it’s such a difficult topic, but it is a difficult topic.” In fact, procedures – both their development and their management – are anything but simple, Mr Jamieson said in a webinar in November, hosted by the Human Performance in Oil and Gas (HPOG) initiative.

Some of the main considerations around procedures are fairly intuitive. For example, they need to be user friendly, easily accessible and clear; updates to procedures must be managed; and end users must be involved when writing procedures. But as they say, the devil is in the details.

“It’s more about the practicalities… It’s about how do we make procedures work for us and make them a success?” Mr Jamieson said. Moreover, it’s important to recognize that procedures can’t be an effective prevention against major accident risk. “That’s the way we look at it at Shell. We shouldn’t be relying on procedures to manage those. We should try and do more.”

In the webinar, Mr Jamieson provided some practical advice around common challenges in procedures management, including when procedures should be used, what level of detail should be included, as well as the integration of procedures within a management system.

Added complexity

First, it’s important to recognize that not every task needs a procedure. “If we have procedures for everything, that can actually be quite counterproductive,” Mr Jamieson said. Not only do procedures require a lot of administrative work to maintain, but “sometimes we can’t see the forest for the trees because all tasks become the same and we lose sight of the more critical tasks.”

When considering whether a task needs a procedure, think about why procedures are used at all. Fundamentally, procedures should support the people doing the work. They are meant to help users identify errors and minimize the errors in human performance, thereby improving safety. “I think that can sometimes be a bit lost… It feels like people tend to follow procedures because we just tell them to. Understanding why we should use a procedure helps us with knowing when we should use a procedure,” he explained.

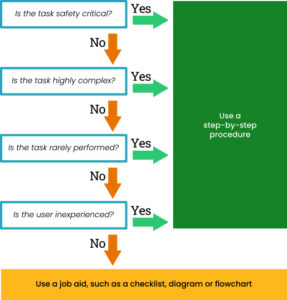

Shell utilizes a flowchart (Figure 1), taken from guidance produced by the UK’s Health and Safety Executive, to help determine whether a given task requires a procedure. It asks four questions:

- Is the task safety critical?

- Is the task highly complex?

- Is the task rarely performed?

- Is the user, or the person completing the task, inexperienced?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then the task requires a procedure. However, even when a full procedure is not required, job aids or checklists could be used. Those tools can help to prompt users on important things to remember when completing the task, Mr Jamieson said. Unlike a procedure, job aids and checklists do not involve step-by-step instruction, so they can be easier to follow.

Once it’s determined that a task does need a procedure, the next consideration is what level of detail the procedure should include. “There’s no simple answer,” Mr Jamieson said, “but it depends on things like: Is it a safety-critical task? How often do we do it? What people are doing it? If it’s simple, familiar, not overly complicated and done by experienced people, you probably don’t need too much detail. But, at the other end of the spectrum, if we know there are safety-critical steps or a lot of steps, we need more detail. This is true even for experienced people. If it’s something that’s done very rarely, you might need quite a bit of detail in the procedure.”

Another thing to keep in mind is that too much complexity within a procedure can make it difficult to follow.

Onsite personnel are often the best people to involve in this step. “It’s about involving the end users, the operators, the technicians, all these people who know the tasks better than anybody else. If we don’t get the right input from them, we can’t have the best procedure. We need to figure out how much detail these people feel they need rather than forcing detail on them,” Mr Jamieson said.

Incorporating flexibility

There are also three common assumptions that are often made when writing procedures, he continued. Certain things are assumed about the way work is done, yet those assumptions often do not reflect real-world operations.

First, companies often assume that work is always done step by step. Therefore, procedures are written to be followed sequentially – the second step does not begin until the first step is finished. “The reality is, when you’re out there doing a job, it’s very rare that you can go through everything in a nice, neat sequence every single time… There are interdependencies between steps, and things that can happen at the same time,” Mr Jamieson said. This means procedures must allow for some flexibility in the way work is carried out.

Second, it’s often assumed that the work is always predictable. “I think we all know that often is just not the case. Work is full of variation. Things will vary from day to day, one hour to the next, and from doing the task one day to the next time you do it. The conditions may have changed a little bit, the equipment may have changed, the weather may have changed, or who’s doing it,” Mr Jamieson said. “The workers have to adapt.”

The third assumption is the worker has full control over the situation. There may be constraints in the time they have to complete the task, the tools they can use or the resources they have at a particular time.

All of this means that procedures must account for the nature of onsite work, Mr Jamieson said. “We can’t just write perfect procedures. There needs to be enough flexibility in our procedures to allow for that variability. If there isn’t, then you know that procedure is going to be difficult to perform.”

Going through the walk-through, talk-through (WTTT) process can be one way to incorporate more flexibility when developing a set of procedures. WTTT is used to collect, record and analyze information about a task to help understand how people actually get that work done. This can be done by meeting with a supervisor to identify the key steps in a task, as well as discuss what can go wrong in each step and under what conditions mistakes are likely to be made.

The WTTT process also helps to identify performance-influencing factors, a range of conditions that could impact human performance on a task.

Mr Jamieson cited the HPOG Procedure Best Practice as a resource to help outline potential performance-shaping factors. These factors include:

Task-related factors, such as complex or badly presented procedures; confusing tool or equipment design; boring, trivial or repetitive actions; or a difficult working environment (noise, heat, cramped conditions, lighting, ventilation);

People-related factors, such as fatigue, stress, inadequate training and physical capability; and

Organization-related factors, such as changes of responsibility without adequate arrangements to ensure capability or competence; a reduction in available resources; inadequate staffing; and poor communication and job planning.

“We should think about the person, the job, the tools they have to use, the process and the communication. How do these things affect how the task is done? How do we factor that into the procedures? By using this (WTTT) approach, we can get better procedures and, ultimately, work becomes easier and safer,” Mr Jamieson said.

The last piece is integrating the procedure into the company’s management system, which involves much more than just saving a procedure somewhere and reviewing it every once in a while. For effective integration, companies should examine their guidance for writing new procedures and identify which steps can be linked with other management processes. For instance, Shell’s process for changing or updating a procedure links into its process for change management. Its process for developing safety-critical procedures links with a separate standard for performing safety-critical task analysis. Its review and assurance protocol for new procedures ties into its audit processes.

“There needs to be a bit of thought about how managing procedures ties into everything else,” Mr Jamieson said. “It’s tied back to human performance. This is taking the systems approach, looking at procedures within the wider system involving the end user, change management, safety-critical task analysis, and it’s injecting human performance into all these different aspects that can all come together to give us an effective set of procedures.” DC

Click here to read the HPOG Best Practice in Procedure Formatting.