Shifting priorities may define offshore rig market post-downturn

The COVID-19 pandemic has done little to blunt the pace of the energy transition. In fact, it may have hastened it. According to Rystad Energy’s 2020 review of global oil resources, released in June, the pandemic – and the oil price downturn spawned in part by the pandemic – have put a lid on exploration in remote offshore areas. As a result, 2020 global recoverable oil resources are expected to drop by approximately 282 billion bbl compared with 2019.

The sharp drop in oil prices seen this year will cause drilling activity to decline significantly in the near term, and the timing of the oil price recovery could coincide with a rise in electric vehicle purchases, potentially hurting the demand for crude, Rystad said. Should demand stay low after oil prices recover, E&P companies may be discouraged from sanctioning projects in more remote areas with longer lead times, leading to a reduction in the number of areas expected to be explored.

Lars Nicolaisen, Senior Partner and Deputy CEO at Rystad, expanded upon these projections at the virtually held 2020 IADC International Well Control Conference in October. He noted that Rystad believes peak oil will arrive in the late 2020s, perhaps as early as 2028, leading to a steep decline in global oil production. By 2030, the company estimates that production could see as much as a 23% decline from 2019 levels.

However, there will still be demand for oil even after peak oil, but E&P companies will likely favor more brownfield, short-cycle activity because they can recoup their investment more quickly than with greenfield projects. In fact, intervention and workovers on existing well activity, as well as the drilling of infill wells, could reduce production decline from 23% to between 5-7%. “What happens to oil supply when if you don’t continue to invest in it? If we do nothing, we’re looking at severe decline numbers,” Mr Nicolaisen said. “We must spend CAPEX on interventions and workovers on our existing well inventory and on infill wells. There’s a lot of work to be done in this industry.”

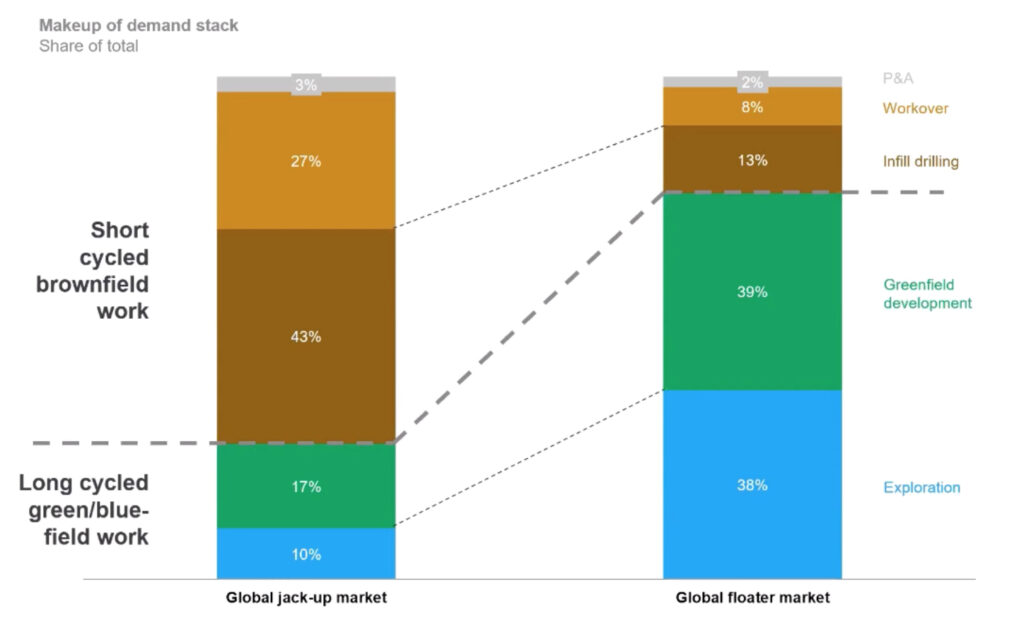

Exploration will be the “key victim” of this shift in focus, which will likely have a negative impact on floater demand. According to Rystad, 38% of the global floater market is currently contracted for exploration activities, compared with 10% in the jackup market. By contrast, infield drilling and workovers account for a combined 70% of the jackup market, compared with 21% for floaters.

In addition, the floater market has seen a drastic reduction in buyers. Rystad estimates only 30 operators will have floaters on contract by the end of 2020, compared with 65 in 2014. This number will continue to decrease as M&A activity increases in the coming years, Mr Nicolaisen said, leading to more oversupply.

“There’s a massive restructuring of balance sheets, restructuring and folding in the world of offshore rig companies right now,” Mr Nicolaisen said. “I believe that, in the aftermath of the restructuring, we will see a consolidation of needs. That will certainly improve the financial health of these companies because it will give them much more pricing power toward their clients.”

Addressing rig supply will not just require drillers to reduce their fleets. The number of drilling contractors in the floater market will also need to contract, he said. While the ratio of floater suppliers to buyers in 2014 was 0.54:1, that ratio became 1.10:1 this year, according to Rystad.

“We’re going to continue to be faced with an oversupplied market,” he said. “I see contours of the drillers addressing that by downsizing their fleets, and I think we’ll continue those efforts. Probably equally important is that the drilling contractors bind together and do mergers. Not only do we have too many assets in the market, we have too many drilling contractors that are bidding in any given tendering situation. If we are able to address that issue by consolidating, you could see a quite constructive outlook.”