Putting people first: Oil and gas industry should consider a system thinking approach to IIoT revolution

Leaders must realize that digital transformation will be 20% technology and 80% how people work together

By John F. Carrier, MIT Sloan School of Management, and Michael Fry, Deepwater Subsea

“Are you digitalizing your business?”

This is the question that people working in the field are being asked at every available opportunity. But is this the right question that the industry should be asking? While it is a good question, perhaps a better question is: “How do we lead our organization through the current digital transformation?”

Unlike previous waves of innovation, there is little in the way of proprietary technology or access to capital that may be used to gain a strategic advantage. Instead, the winners will be determined by how quickly a company adapts its systems to the ever-changing needs of the market and the oil reservoir, not by the physical assets it owns.

Industrial Internet of Things

The opportunity for the oil and gas industry is estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars per year. This is supported by two inevitable driving forces:

• The utilization gap of heavy capital equipment across the industry, exemplified by the great deal of variation across individual assets; and

• The cost-effective availability of the technology to provide a “global nervous system” to observe and manage the portfolio of far-flung assets in near real time.

In terms of technology adoption, the oil and gas industry is on par with automotive and aerospace. However, the oil and gas industry has, in the past, successfully resisted full adoption of front-line workforce management best practices, such as continuous improvement and lean manufacturing, despite the clear and overwhelming benefits.

Certainly, the oil and gas patch is not an automobile factory. For instance, automotive plants don’t move every few weeks, and the temperature is rarely outside of a 68-72°F window. “Taking a look” means walking a few hundred feet, not getting on a helicopter. However, the industrial internet of things (IIoT) has closed the communication gap that previously insulated the oil and gas industry from adopting standardized work and lean operations.

A third driving force is the privilege to operate in an era of immediate and ubiquitous transparency. For this reason alone, adoption by the oil and gas industry will not be optional this time.

The Role of the Front Line in Technology Adoption

A transformational moment in the history of professional racing was the realization that one second saved in the pit has the same value as one second gained through optimization of engine technology. However, given the advanced state of engine technology, a dollar invested in pit crew performance handily beats technology investment on all three of these critical factors:

• Investment-to-realize value;

• Time to implement; and

• Risk-reward impact

The third is particularly relevant, as optimizing technological performance increases risk by making the system run faster “on the track”; whereas reducing pit crew service time reduces risk. Risk is pushed “off the track,” where teams can train and synchronize to deliver precise service to the car under severe time constraints.

The oil and gas industry is in a similar position, as the speed of drilling technology advances has greatly outpaced advances in the system supporting drilling operations. It is critical that companies avoid investing in “the shiny penny of technology” when looking to improve operations. Instead, they should look at the “hidden factories” that have evolved to firefight defects in planning, logistics, materials and crew competence in order to keep the rig up and running.

Think Technology Rejection, Not Adoption

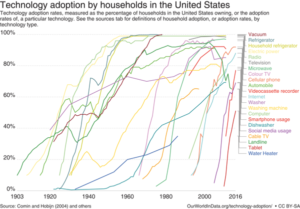

The past two centuries have experienced unprecedented rates of technological adoption. However, when projecting the technology adoption curve at a facility, it is more valuable to consider technological rejection, not adoption.

As an example, the benefits of an organ transplant is fundamentally clear, yet the body often still rejects it. Similarly, a work facility may reject a new technology not because it does not bring overall systemic value but because it is identified as something that interferes with daily work.

Let’s look at a major manufacturing firm that introduced augmented reality (AR) glasses to its front lines to provide real-time instructions and feedback communication. The front-line staff rejected them. The reason was the AR glasses made them nauseated. By replacing the AR glasses with an improved form factor that greatly reduced impact to peripheral vision, the company was able to eliminate this barrier to adoption, while respecting the needs of the front line.

This can be seen out on the rig. The adoption of technology in the oil and gas industry is like the competency curve of learning. As soon as technology causes a delay in productivity (denial/frustration), it will be rejected by management. It’s up to the front-line leaders to embrace it, promote it and utilize it.

Key to the Transformation: The Front Line Leader

According to extensive work done by author TJ Larkin on front-line leadership, the front line places the greatest trust in information that comes from their front-line leader over any one else in the organization. Unfortunately, the front-line leader’s time is overwhelmingly controlled by the system – workarounds, firefighting, calls from corporate, paperwork. This pulls the front-line leader away from being in the workspace with the front line. Circumventing the front-line leader while adding more work requests to the front line is a recipe for rejection.

There is a simple answer to this: The first round of projects should all be focused on freeing up the front-line leader’s time. When in doubt, invest in preparation prior to daily execution.

The front-line leader manages the challenge of balancing resources between today’s production and transformation to tomorrow’s oil field. Given that the front-line leader is saturated with current responsibilities, there is little time for thoughtful review and preparation of how to sequence the technological transformation in a way that reduces, rather than increases, workload on the front-line leader and his or her staff.

The compounding factor is top-down pressure from senior management to complete the digital transformation on an aggressive timeline that is ignorant of the learning step required in any major organizational transformation.

The oil and gas industry is finally starting to see the value of exposing its front-line leaders to operational data. With the development of business intelligence software and self-service predictive analytics, today’s front-line leaders now have the tools and data available to make critical decisions based on what the systems are telling them and not just based on their past experiences.

Where the problem lies is that, if they’re not educated on the value of these tools, they will quickly reject them.

AI meets ‘Get-’er-Done’: A Workspace Transformed

People who have spent their careers in operating environments know the value of quick thinking during times of systemic stress, whether that be an oil field, an assembly plant, a hospital operating room or even during preparation of metrics reports for the weekly meeting with executives.

Risk increases significantly under these conditions, as there is no time to challenge assumptions, check calculations or consider alternatives. In the worst case, the industry can experience a catastrophic effect with unacceptable consequences to human life and the environment.

Why do these events occur? They occur when the speed at which the system is evolving exceeds the rate at which individuals can think and act clearly. The right answer under any circumstances is to slow the system down until it is under control.

However, one advantage of computers is their ability to analyze massive amounts of information much more quickly than any human can, by using well-developed algorithms. In a relative sense, speeding up the ability to think is equivalent to slowing down the system. This phenomenon is well-known through industrial controls – no number of humans can think quickly or accurately enough to keep a 400,000-bbl/day refinery up and running safely.

Thanks to the new wave of IIoT technology, it will soon be possible to bring together the front line, subject matter experts from around the world, and massive computational power to produce significantly better decisions in significantly shorter time.

There is a caveat from the world of chess. Current chess programs, supported by massive computational power and memory, have reached the level of human grand masters. What is often lost in this message is that a good human plus a good computer is far superior to either the chess grandmaster or the world-class computer alone. In a world where the game is played on a dynamic rig floor and not a fixed chessboard, the role of humans in this equation is even more important in order to drastically reduce downside risk while increasing productivity.

Key Factors on the Journey

• Get a new perspective, either by bringing in a new set of eyes to observe daily operations or by taking a field trip with staff to see first-class execution in another industry.

• Test before buying, given that everything from helicopters to computer time can be bought as a service;

• Think carefully through the IIoT platform strategy prior to scale-up;

• Realize that maintenance is the foundation of transformational change. Restoration is a form of transformation and requires a cultural mindset where “running systems down” is not acceptable; and

• Ensure that the technology introduction is sequenced in a way that empowers front-line leaders.

The Key Competitive Advantage: Talent at the Edge

Where is the money made in oil and gas? Where is all the risk? The answer to both questions is the same: at the edge. While there has been a lot of discussion around computation at the edge, the real advantage is to enable the company’s entire set of resources (“talents”) to be put out at the edge, available at the front-line leader’s fingertips as needed.

This essentially flips the current command-and-control HQ-rig reporting structure. The value is that the time to respond correctly to conditions on the field is reduced from days to minutes, if not seconds, informed by subject matter experts from around the world.

Thus, the transformation will be 20% technology and 80% how people work together. In the words of Professor John Van Maanen at the MIT Sloan School, “Culture is a problem-solving device created by people to solve common problems.” In short, the companies with the best cultures will ultimately thrive. DC