Training, processes underpin industry’s well control efforts

Project also under way to help assess skills, knowledge of BOP maintenance personnel

By Joanne Liou, associate editor

As industry addresses increasingly complex well designs using increasingly sophisticated equipment, the focus of well control remains constant – prevention and early intervention. This means “simply recognizing that something is not right,” Richard Grayson, manager – HSE & training for Nabors, said. “The most important thing is simply that the driller knows what’s normal. If it’s abnormal, he closes the well because he has that authority. He doesn’t ignore what the wellbore is telling him.”

At the foundation of industry’s well control efforts are people, where wider industry challenges of hiring and training new crews trickle down to well control, as well. “It is a huge challenge because we need 22,000 to 24,000 people in the next 24 months, including backfills, to take care of the newbuild rigs,” A.J. Guiteau, director – learning & development for Diamond Offshore Drilling, said.

“It ties directly into well control because you have to have competent people to be able to run the rigs and know that they understand what needs to be done in well control,” added Moe Plaisance, vice president, government & industry affairs for Diamond Offshore.

On the technology front, however, real-time monitoring and automated rig technology, combined with multiphase flow modeling, are helping to determine optimal solutions to well control incidents. Further, industry is building upon blind rams and shifting focus to blind shear rams that can cut any tubular to shut in a well. Companies active on the US Outer Continental Shelf are working on calculations to prove that their equipment can cut anything in the wellbore in cases of emergency and seal it off, Mr Grayson explained. “With the aftermath of Macondo, we’re being asked to have third-party engineering companies that will look at the equipment, look at the pressures, do some calculations and essentially show in an objective way that the equipment can cut whatever tubular – all drill pipe – is being anticipated to be in the well.”

Better processes around equipment maintenance and incident analysis also are contributing to well control efforts. Chevron, for example, recently enhanced its equipment maintenance reporting system to provide a way to share lessons learned, William Averill, BOP reliability team lead, Chevron, said. Going beyond competency, he also suggests that industry implement a licensing scheme for BOP technicians and engineers to further “professionalize” subsea engineers.

BOP maintenance

BOP maintenance planning and execution is continually evolving. While the OEM establishes the baseline for care, those plans are then augmented by best practices and the results of lessons from the drilling contractors who own the equipment and from the operators who take additional steps, such as more frequent replacement of elastomeric parts, to enhance reliability, Mr Averill told Drilling Contractor.

Chevron’s Deepwater Exploration and Projects (DWEP) business unit is focused on the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), with five drillships in operation. The company has two in-house teams of offshore BOP specialists and subsea engineers that constantly provide feedback to the drilling operations team to ensure that lessons learned on one rig are transferred to the others. One team is focused on deepwater GOM, and the other oversees deepwater activity outside the GOM.

To enhance reliability, collecting data on issues with parts and problematic operations plays a significant role. “We’ve been doing this for a number of years and have sent this information back to OEMs and other stakeholders,” Mr Averill said. Chevron recently enhanced its equipment maintenance reporting system with the online FRACAS program – Failure Reporting Analysis and Corrective Action System. The system is accessible to engineers located offshore and includes a “lessons learned” function, which can be referred to during subsea pressure testing or riser deployment, for instance.

“The beauty of the system is that it will enable us to do better trend analysis and connect the dots with related issues on other rigs in our system,” he said. “Systems like this demonstrate our commitment to operational excellence and allow us to run a safer, more consistent operation unhindered by equipment problems.”

“The beauty of the system is that it will enable us to do better trend analysis and connect the dots with related issues on other rigs in our system,” he said. “Systems like this demonstrate our commitment to operational excellence and allow us to run a safer, more consistent operation unhindered by equipment problems.”

Each maintenance cycle is planned around the well on which the BOP will be used next. “We first define the BOP configuration – drilling or completions – water depth, expected duration of the operation and other conditions. This information comes together with output from the contractor’s maintenance system, which tracks and schedules particular tasks for upcoming maintenance opportunities,” Mr Averill explained. Chevron’s engineers work with contractors to review the plan and verify that it includes steps for any special tasks or upgrades available from the OEM. “When necessary, we coordinate with third-party inspectors and BSEE to clarify expectations of the testing and permit program so there are no surprises.”

License to work

In terms of BOP equipment, the human element is a common theme among various issues that lead to nonproductive time (NPT), Mr Averill stated at the IADC Subsea BOP Workshop earlier this year. This is not limited to newhires but includes seasoned subsea engineers, as well. “Without good folks consistently maintaining the kit, all the new high-tech bells and whistles will not work as intended,” he said.

Advocating competency assurance, Mr Averill discussed the need for a formal certification or license that verifies a person’s experience, knowledge and skill has been demonstrated and meets the level of training required. Implementing a license system would help create transparency and consistency for training among drilling contractors.

Following the IADC Subsea BOP Workshop held in Houston in April, operator and contractor representatives have met to discuss methods of assessing and certifying skills and knowledge for BOP equipment maintenance personnel, from entry to supervisory levels. With the Center for Offshore Safety, a workgroup began work on a project called subsea engineer competency assurance (SECA) and is drafting guidelines, first focusing on entry-level workers. The group plans to have elements of the program defined and agreed upon by the end of the year. An industry body will govern the competency assurance standard, Mr Averill noted.

IADC is participating in the workgroup and will potentially include the guidelines in its WellCAP program, Mark Denkowski, IADC vice president of accreditation & credentialing, said.

Mr Averill believes such a standardization is much needed, citing licensing requirements in other industries and for other tasks, such as to drive a car or to be a doctor or aircraft mechanic. “For BOP technicians/engineers, the work that he does on a day-to-day basis requires the same types of skills and attention to detail that these other professionals have at their jobs. I think we need to formalize the critical role subsea engineers play in deepwater drilling operations.”

With subsea engineers, formal certification would give them something that stays with them. “The professionalism of the maintenance crew equates to lower NPT and enhanced safety,” Mr Averill stated. “Operators and drilling contractors will both be able to sleep easier at night knowing that the equipment is in good hands and not have to worry about issues arising. OEMs will be able to rest easy knowing that their equipment carrying their name is being well cared, knowing that there are formally certified engineers and maintenance professionals working on the equipment.”

On-the-job training still remains a great practical training method, he said, but “we also need better classroom training, a proper assessment in testing and supervisor signoffs with formal certification or license – a point at which the subsea engineer or a supervisor can circle back to check and make sure that his work or skill has been demonstrated and meets the level of training.”

Developing technologies, systems

To stay ahead of the challenges associated with increasingly complex drilling environments, Boots & Coots, a Halliburton business, has been working on improving technologies for modeling computational flow dynamics (CFD). CFD can assist with relief well planning by determining, for example, if one relief well will be adequate, what size the well should be, the fluids needed, and the rates and volumes needed to kill the target well. “If you’re planning to drill the well, now you need to take into consideration how you would attack that well with the relief well should you lose control,” Douglas Derr, global well control & prevention/RMS ops manager at Boots & Coots, said.

Modeling flow of reservoir fluids involves complex issues where the equations might exist, but the trick is to get those equations in a usable format. Modeling ranges from determining forces on a subsea capping stack prior to landing on the blown-out well to determining potential flow rates from a well. “In the past, models commonly used in the industry would make a run for a given set of parameters,” Mr Derr said. To change a parameter in a model, such as downhole temperature to see the effect it would have on the flow rate, would have taken days or a week to execute.

“Where we’re getting now is much more complex programming. We can actually put those variables on a dashboard-type arrangement and in modular format so we can add complexities to the program (in real time),” he explained. “In the form of sensitivity studies, we see how the final outcome varies with any given variable or set of variables. Instead of changing one variable at a time, we can model effects of several variables simultaneously.” Results can be available in hours instead of days.

Increasing applications of managed pressure drilling (MPD) around the world also is helping with earlier detection of influxes. “That’s MPD’s whole purpose. It allows you to drill wells with a narrow margin between the pore pressure and the frac gradient,” Mr Derr said. By definition, MPD provides early kick detection and is designed to keep the well on the narrowest possible pressure margin without losing mud downhole, he explained.

The technology could have significant impact on deepwater operations going forward. “In deepwater, pore formations are not as strong, so the windows are narrower,” Mr Plaisance of Diamond Offshore stated. “By using MPD, you can maintain and stay within that window without exceeding it.” He believes the key is to make MPD successful as a process and enhance the economics of drilling, not necessarily making it an everyday practice. “In the future, it’s going to make completions much easier, more cost effective and more predictable,” he continued.

In unconventional shale plays, Shell sees main challenges in the long horizontal stretches of the wellbore. “If you do take a kick, they don’t handle the same as vertical wellbores. There are some differences in the way those act as you try to circulate the kick out,” Deepak M. Gala, SME – well control engineering for Shell, said.

Shell is applying near-balanced drilling, or underbalanced drilling (UBD), with downhole pressure, volume and temperature devices that support trend analysis and real-time monitoring. In a well control event, given the available data, “we’re able to do a better job of determining what went wrong, and that may help us get out of the challenging situation faster,” Mr Gala said.

Through Shell’s drilling automation rig technology program and real-time operating centers, experts are working from one location, centralizing best practices and expertise. “We have more layers in this particular environment that can catch the potential human error,” Marco op de Weegh, team lead – well control engineering for Shell, said. “Looking at particular trends that are already matured in the field, you have a higher probability of catching potential errors that have been made by those in the field. With unconventional plays, the reservoir is considered tight, with restricted flow from reservoir into the wellbore, and allows the drilling phase to be underbalanced versus the required reservoir pressure normally used to be balanced or overbalanced for conventional plays, and you need that monitoring and full awareness.”

With UBD, the volumes of gas allowed into the wellbore are minimized, and the time that is allowed to respond to an unplanned kick is also lessened. While drilling in unconventional plays, the norm is not to have production volume exposure as the reservoir has to be stimulated after the drilling phase to establish production rates, Mr op de Weegh explained.

While kick intensity is mitigated, kick tolerance is increased. “During the execution of these projects, you actually have already established the subsurface and reservoir behaviors and you build in that engineering capability and understanding. You’re de-risking your trouble zones that you might encounter.”

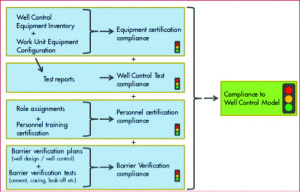

Another system Shell is using to manage well control risks is eWCAT, the electronic well control assurance tool. The web-based system captures equipment certification for well control equipment, personnel certification, BOP tests and barrier status. eWCAT was implemented in 2011, beginning with deepwater operations. The tool, which has been applied to deepwater Shell well projects, is expected to soon reach full implementation to include onshore operations. “It is a verification program and process where we want to identify the equipment that is related to well control and make sure that the integrity of that equipment is in place by verifying, for example, the certificates of compliance according to the OEM and the international standard like API,” Mr op de Weegh stated.

Training and procedures

Drilling contractors and operators alike are refining training programs to incorporate new well control technologies and to ensure competency. At Shell, personnel in its Wells organization follow a cycle where they alternate between completing an in-house advanced well control course and an industry well control certification. This allows them to refresh their knowledge every year rather than every two years, Mr Gala said. Shell also aims to share the well control course with the industry to encourage similar learning programs.

New equipment may be leading to the need to revise rig procedures, according to Nabors. “We’re beginning to work with subsea intervention devices (SIDs) at the sea floor of the GOM. Since we are primarily a platform company when working offshore, we typically have a surface stack,” Mr Grayson of Nabors said. “Now that we’re working with SIDs in some places, we are having to rethink some of our procedures.” SIDs are annular preventers placed above the seabed, and “we’re seeing more of those, which allow the flow to be shut in at the seafloor even when there is a surface stack.”

Working with the IADC Training Committee, Mr Grayson says he’s also helping to push for quality instructors for the industry. “We’ve done a lot of work on making sure instructors have industry experience or a great deal of high-level education,” he said. “There are requirements within the IADC WellCAP to ensure instructors have appropriate education, experience and training. WellCAP requirements for instructors have been in place for a while, and they have changed somewhat over time. Not just anyone can be an approved well control instructor. ”

People remain at the center of well control efforts, both in numbers and quality. “We’re in a huge challenge for the number of people, the right kind of people, as well as the right kind of training,” Mr Guiteau of Diamond Offshore said. Companies, such as Diamond Offshore, are actively seeking newhires to address the shortage of personnel in the industry. Diamond Offshore recently hired 24 assistant engineers from eastern Europe who are former maritime academy graduates to become subsea engineers. “Their industry is declining in terms of what they want to do,” Mr Guiteau explained. “They came over to us, and they are the perfect fit. They already know what it’s like to work offshore. You have to find those kinds of recruiting niches and develop them.”

MPD adds another dimension to training because it requires a higher level of knowledge from personnel.  While the physics and foundation of well control remain the same as traditional practices, MPD adds “complications to things they didn’t do in the past,” Mr Guiteau said. “They have to be more capable of expanding, transgressing and growing in that knowledge.”

While the physics and foundation of well control remain the same as traditional practices, MPD adds “complications to things they didn’t do in the past,” Mr Guiteau said. “They have to be more capable of expanding, transgressing and growing in that knowledge.”

Diamond offers MPD training in concert with its equipment vendors. “This training is offered to the crews who will be involved in an MPD well right before startup of the MPD well,” he noted. “The course usually entails a review of the equipment and its functions, along with the drilling practices associated with it in an MPD plan.”

In March, Diamond Offshore opened the first phase of its 30,000-sq-ft Ocean Technology Center in Houston to help address the increasing complexity of drilling technology and equipment. A $9.2-million investment, the facility was designed to centralize a multitude of training, including traditional and electronic drilling, crane training and stability and ballast control, into one location.

The center contains 19 simulators, all used in some form of well control training, Mr Guiteau noted. “Well control and stability classes are already under way, as well as technical classes in electrical and subsea areas.” At the center, the focus is on learning through simulation rather than lectures to raise the level of understanding and competency of personnel. The center will be fully operational in August 2013, offering drilling practices classes designed specifically for drilling personnel. The center will also be home to Drilling the Well on Simulator (DWOS) and customer spud meetings with well control scenarios. Diamond Offshore expects to train 1,200 students at the center each year.

Reliability and predictability

A resounding theme across well control is an emphasis on reliability – the ability of a system to perform a function not only under normal circumstances but also in unexpected situations. “Reliability in this world means you keep drilling,” Margaret M. Buckley, product/project manager, DTC International, said. Beyond that, industry should take an extra step to actually predict failures, she said at the IADC Subsea BOP Workshop earlier this year. “The area we really need to improve on is predicting. We can make the individual components as reliable as possible, but in reality, components move and wear. We can replace them on a regular basis, but the best way is to know when they’re going to fail and get them out without having to stop drilling operations.”

Control systems for BOPs have evolved over the years, but repairs are still completed in between wells when the entire system is offline. Ms Buckley urges industry to look to other industries like aerospace and aviation for improvement opportunities. “We’re taking components that have been field tested, and now you have to be able to predict when are these things going to fail. You have to be able to monitor what’s down there.” To monitor BOP control systems and try to predict failure, extra sensors must be installed to provide data, and software must be available to analyze that data. “It’s costly to add this type of monitoring to existing systems,” she added. “It has to be incorporated in the beginning.”

Control systems for BOPs have evolved over the years, but repairs are still completed in between wells when the entire system is offline. Ms Buckley urges industry to look to other industries like aerospace and aviation for improvement opportunities. “We’re taking components that have been field tested, and now you have to be able to predict when are these things going to fail. You have to be able to monitor what’s down there.” To monitor BOP control systems and try to predict failure, extra sensors must be installed to provide data, and software must be available to analyze that data. “It’s costly to add this type of monitoring to existing systems,” she added. “It has to be incorporated in the beginning.”

DTC International has developed MODSYS, a subsea modular control system that performs real-time trending to identify BOP component degradation before failure and utilizes an ROV to retrieve control system components, reducing the need to pull a stack. “Everyone has been on airplanes using these same components. We’ve miniaturized them,” Ms Buckley explained. “We have compact packaging on these components, but to reduce some of the problems on it, we’ve eliminated a lot of the leak paths by not having any tubing or fittings inside the module (of the control system). When you have all of this data coming back, all of your monitoring points for pressure and time and voltage, then you have to analyze it; you have to predict (a failure).” DTC has deployed two MODSYS systems: one in Brazil on a drillship and one in the GOM on a production platform. The one in Brazil is an acoustically initialized MODSYS control system that has been operating on a BOP stack of Aban Offshore’s Aban Abraham for the past two years, in 8,000 ft of water. In the GOM, a MODSYS control system has operated for more than 20 months on a subsea isolation device from a platform in 4,000 ft of water for ATP Oil and Gas.

If the data that comes back points to a problem, the next step is to bring the component to surface. “To retrieve, troubleshoot and repair control systems on deck and retest it and to go back subsea is very time-consuming and nonproductive,” Ms Buckley said. The modular system reduces the time to retrieve equipment for repair with an ROV that descends with a replacement module and installs it, taking approximately four to eight hours, whereas current systems require LMRP to be retrieved, which can take three to seven days. The system can be configured to work with all BOPs and production and workover equipment

“At dayrates where they are, we have our systems modularized to the point where you can go down, bring a module up with an ROV and put a new module in before you even come back. It saves a lot of time, but mostly it keeps you working,” she said. “You’re taking all of these components – valves, solenoids, regulators. You’re not giving up any of the functionality of it, but you’re taking all of these components and putting them in packages that are very compact and able to be brought back to surface with an ROV.”

MODSYS is a registered trademark of DTC International.