By Maggie Cox, editorial coordinator

and Mike Killalea, editor/publisher

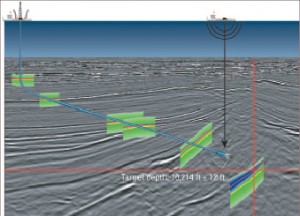

The prize: a sprawling ultra-deep – and ultra-deepwater – reservoir spanning hundreds or thousands of square miles and approaching a mile thick in places. Estimates of potential reserves vary from 4 billion boe to 15 billion boe.

But nothing is easy. Among the challenges is a hovering sheet of salt that can measure 10,000 ft–16,000 ft and standing atop a treacherous layer of geologic junk. And the prize itself — the Lower Wilcox Trend, which lies as deep as 36,000 ft.

But, if you want a deed accomplished, tell a driller it’s impossible.

The battle to drill through salt inclusions and the so-called “rubble” zones have been the subject of several technical papers, some key ones presented at the 2010 IADC/SPE Drilling Conference.

The Gulf of Mexico is a veritable laboratory, not only for deepwater but for deep drilling. Wells have moved increasingly deepwater over the years, and the trend appears to point squarely in that direction for the future. These increasing depths, where pressures can exceed 25,000 psi, pose enormous strains to equipment, both at the surface and downhole, and pressure control equipment. Service companies say they are ready for those pressures, though. For its part, Schlumberger says that its tools are pressure rated. This can be up to 30,000 psi in the same wells.

Time and experience have alleviated some of the difficulties associated with drilling salt domes, simply as a function of the sheer number of wells drilled. The resulting offset data from the last three to four years has proven invaluable in planning today’s projects.

RECORD WELL

Along the way, the industry continues to set records. In its Jack 2 well, Chevron drilled its deepest well in a deepwater salt project. The well was also the deepest where the operator had ever set 22-in. casing. A deepwater salt drilling team of experts from Chevron and Schlumberger wanted to save rig time and cost by drilling the long 26-in. hole section of the Jack 2 Gulf of Mexico well with a single BHA.

It was a challenging goal, Schlumberger says, because seven BHAs had been required to drill the equivalent section of an offset well. The team met the challenge by using a BHA that enabled it to optimize hydraulics and hole cleaning and mitigate shocks and vibration while drilling through caprock and “dirty salt” to section TD.

This BHA had a specially designed 26-in. bias unit PowerDrive vorteX powered RSS running with a PowerDrive X5 RSS. It also included an arcVISION 900 9-in. drill collar resistivity tool, an APWD annular pressure-while-drilling sensor, and a PowerPulse MWD telemetry system with a 25 7/8-in. stabilizer sleeve to assist shock mitigation. With this BHA, the team was able to drill out the 36-in. casing and continue to TD in a single 2,642-ft run – 1,580 ft of it through a hard salt formation.

During the run, the initial hole inclination of 2° was gradually dropped to vertical and maintained there to TD using the 11-in PowerDrive X5 RSS in its inclination-hold mode. A flow rate of 1,200 gal/min maximized hole cleaning, MWD data enabled the drilling team to monitor and mitigate shocks and vibration, and real-time interpretation of the arcVISION900 resistivity log guided adjustment of drilling fluid salinity to help maintain hole gauge.

Drilling the 26-in. hole section of Jack 2 in a single run with 1 BHA saved an estimated five days of rig time, compared with using seven BHAs to drill the equivalent section in an offset well, the service company said. At a rig spread-rate of US$610,000/day, the reduced drilling time saved Chevron US$3.5 million. In addition to saving rig time and cost, the elimination of six BHA trips reduced mud cost because mud returns were to the seabed.

Excellent directional control enabled the team to drill the “gun-barrel” borehole as planned. The 22-in. casing was run without incident, eliminating the need for a 28-in. contingency casing string – and its cost.

TROUBLE BELOW SALT

In distant geologic time, the salt lay at depths of 30,000 ft to 40,000 ft, but, being of lesser density than the shale, over millions of years it rose through breaks in the formation, creating the huge salt domes seen today. At the same time, however, it dragged with it a cocktail of sedimentation, which now resides below the salt, and, in industry parlance, is known as the “rubble” zone.

The term is a misnomer, however, points out Robert Clyde, North America and Latin America drilling engineering manager for Schlumberger, who prefers the term “unknown geologic zone.”

Whatever it’s called, this subsalt sediment is tricky to drill, observes Riaz Israel, North Gulf Coast drilling engineering center manager, Schlumberger. “One of the biggest things drilling through that zone is it’s difficult to determine what the pressure in an inclusion or at the base of the salt is,” he said.

“It can be a low-pressure zone and have losses, or it can be a high-pressure zone, which can result in a kick. There’s a lot of uncertainty, exactly what that pressure regime is.”

Tarry bitumen is also frequently found in this area, added Mr Israel, who co-authored “Drilling Deep in Deepwater: What It Takes to Drill Past 30,000 ft” (IADC/SPE 128190) and “Challenges Evolve for Directional Drilling Through Salt in Deepwater Gulf of Mexico,” published in the May/June 2008 DC.

“These typically occur at the seams of these formations,” Mr Israel said. “It is 99% asphalt, and a lot of operators who drill into that find it a big-time problem.”

Uncertain pore pressure is the issue. “The problem stems back to the salt,” Mr Clyde said. “Today it’s turning out to be a very good formation to drill, if you are ready to drill it in the right manner. One major challenge is understanding what the pore pressure is in the salt. If you are able to understand the pore pressure in the salt, you can project ahead and understand the pore pressure below the salt.” In the tar and rubble, that is.

According to Tim Carroll, directional drilling coordinator, Halliburton Sperry Drilling Services, patience is key to getting through these areas.

“Rubble zones are known for being unstable, causing problems with hole collapse, pack off and increased torque,” he said. “Setting another string of pipe too soon or trying to ream through the area too fast may cause the drillstring or the BHA to become stuck.”

Controlling circulation loss while drilling these trouble spots is also a concern. Mr Israel said, “Once you are close to the expected base of salt, typically you would reduce your rate of penetration (ROP) and start what we call control drilling so you can very quickly spot any changes in your drilling parameters.”

From the customer perspective, drilling through salt raises issues such as decreasing connection time to manage invisible lost time (ILT). “Decreasing ILT is something all of our customers are starting to look at, considering the extremely high drilling cost in deepwater,” Mr Carroll said.

Halliburton is using rig-time programs to determine where time is lost and to determine the discrepancies in crew connection and ILT times, Mr Caroll said, adding that not back-reaming or circulating as long between connection times would help mitigate this issue.

MODELING

Accurate modeling, particularly using finite element analysis, in and around salt bodies, is a 3D problem, as traditional 1D mechanical earth modeling often breaks down in this environment.

“We work with geomechanics specialists to understand the impact that the pore pressure and fracture gradient have in the drillable window, combining the geomechanics departments both in the oil company and Schlumberger to integrate a lot of those key areas,” Mr Clyde said.

SEISMIC

Even with advanced modeling, it is difficult to predict these pore pressures. However, advances in seismic technology have come to the rescue, both in running seismic from the surface and in analyzing the results. “The ability to make seismic charts while drilling,” Mr Clyde said, “and pick up these reflections lets you know when you are getting close to the base.”

Drilling parameters change as one drills out from the base, so the use of at-bit measurements, particularly an at-the-bit gamma-ray measurement is very important.

“That’s very important, because the drilling can be slowed down momentarily while the pore pressure is established, along with annular pressure-while-drilling measurements,” he continued. “Once that’s established, the mud weight can be changed and the well drilled ahead more effectively, or the casing set before the new pressure regime.”

CONCERNS IN THE SALT

Due to its plasticity, salt is not that difficult to drill, with certain caveats, including vibration at entries and exits and well non-verticality, which can lead to wellbore instability.

Halliburton’s Mr Carroll said, “The one biggest factor for drilling salt is the ratio of overburden of mud weight to salt. We have proved this time and again the need for 85% to 95% overburden to eliminate vibrations and stick slip while drilling.”

By enabling finite element analysis, drillstring vibrations can be simulated and equipment adjustments can be made to avoid drilling disruption and increase the ROP.

“Bit and concentric reamers are usually the biggest sources of excitation forces for a drilling assembly when drilling,” explained Mr Clyde. “When we look at the design of the drilling assembly, before execution we make sure that the bit, the reamer and the rest of the drillstring is matched.”

KEEPING IT VERTICAL

The pressure in and around salt changes the way the formations behave, resulting in salt creep, over- or -underpressured zones, and a significantly faulted environment, Dustin Vulgamore, well construction engineering manager GOM, Baker Hughes, commented.

Maintaining verticality while drilling salt has always been challenging due to shale or anhydrite inclusions.

Nitin Sharma, drilling applications engineer, GOM, Baker Hughes, described the ways in which the company has been able to maintain verticality while drilling salt.

He explained that by using the AutoTrak rotary steerable system in “hold” mode for verticality in combination with the company’s CoPilot real-time drilling optimization service, they are able to drill in salt without any directional deviation.

Essentially, this rotary steerable has the ability to adjust the steering forces as needed and maintain the target inclination. It also has an option of “ribs off” mode to retract the ribs to prevent tool damage when needed, for instance while back reaming.

“If you couldn’t close those ribs, imagine those points sticking out while you’re picking up off bottom. Those ribs could catch on micro-ledges and actually damage the tool. Consequently, when you go back to drilling, you don’t have the same directional control,” Mr Vulgamore said.

Mr Sharma said upper rubble zones occurring above the salt sometimes have salt fingers, or inclusions, at the entry. Deeply dipping formations present additional challenges. During salt entry and exit, controlling vibrations with real-time monitoring and optimization with CoPilot is critical to prevent drilling dysfunction. “Proper bit selection, stabilization of the bottomhole assembly, and bit and reamer synchronizing help control vibrations.”

CRITICAL PERSONNEL

However, while equipment improvements are important innovations to completing any well, preparing employees to handle these advancements and making sound decisions is something Schlumberger isn’t overlooking.

“One of the most important things to consider going along with all of these advancements is the experience we have with personnel,” Mr Israel said. “We have adapted our Deepwater Certification Program, which allows us to train our engineers in the techniques so they better understand the issues in drilling these deep wells and drilling through salt.”

Introduced worldwide as a pilot about 18 months ago, Schlumberger’s Deepwater Certification Program was formally rolled out over the last year. In addition to certifying well-design engineers, the program also extends to wellsite personnel, such as directional drillers, who generally guide jet-in drill ahead operations.

“It’s proven to save time in the drilling operations, particularly when we couple it with our 26-in. rotary steerable system,” Mr Clyde explained.

SHORE SUPPORT

Using real-time centers and monitoring has increased success in the GOM, bringing heightened awareness, across the company, to the consequences of drillstring vibration. “Real-time monitoring is critical for drilling wells today, not only in salt,” Halliburton’s Mr Carroll said. “Remote operations centers bring all of our experiences to the front and enables us to utilize more personnel that may not have the salt experience.”

Schlumberger’s operations support center helps control vibration during salt entry and exit with real-time vibration monitoring. OSC personnel can see how various components of the BHA pass through the salt and correlate that to a time plot. “We can see the reactions as we change parameters and how that affects shock and vibration,” Mr Clyde said. “Therefore, we can recommend how to adjust these drilling parameters.”

References & Resources:

PowerDrive VorteX, PowerDrive X5 RSS, arcVISION 900, PowerPulse MWD telemetry system products are trademarks of Schlumberger.

AutoTrak and CoPilot products/software are trademarks of Baker Hughes.

The GeoPilot program is a trademark of Halliburton.

The first three papers cited below were presented at the 2010 IADC/SPE Drilling Conference, 2-4 February in New Orleans.

1. “Drilling Deep in Deepwater: What It Takes to Drill Past 30,000 ft” (IADC/SPE 128190), C Chatar, R Israel, Schlumberger, and A Cantrell, Devon Energy.

2. “Salinity-based Pump & Dump Strategy for Drilling Salt with Supersaturated Fluids” (IADC/SPE 128405), T J Akers, ExxonMobil Development Company.

3. “Opportunities and Challenges of Deepwater Subsalt Drilling” (IADC/SPE 127687), R Mathur, Baker Hughes, N Seiler, Pardo, Baker Hughes.

4. “Challenges evolve for directional drilling through salt in deepwater Gulf of Mexico,” RR Israel, P. D’Ambrosio, A.D. Leavitt, Schlumberger; J.M. Shaughnessey, BP America; and J. Sanclemente, Chevron North America E&P; Drilling Contractor, May/June 2008. Available on www.DrillingContractor.org.

Good article, but there was no mention of the roll that the drilling fluid pays in successfully drilling these wells.