Drillers’ Situation Awareness model identifies key cognitive skills needed to be a good driller

Three-year project looks beyond technical competence in search of ways to enhance drillers’ thinking skills

By Ruby Roberts, Industrial Psychology Research Centre, University of Aberdeen

“Being a good driller is more than running equipment and drilling a hole. It is also having an accurate picture of what’s going on in the well and on the rig so you are able to make the right decision at the right time.” — Maersk Drilling OIM

Considering the complex nature of a driller’s job, it may seem obvious that a good driller needs to have high-level awareness of the well, recognize the indicators of an escalating situation and be confident to take the decision to shut-in. Being a good driller is more than being technically competent. Yet, until recently, these vital thinking skills were not necessarily being trained or assessed across the drilling industry.

This is changing for the better, with industry recognizing the importance of teamwork and cognitive (i.e., non-technical) skills for safe and efficient performance, as was discussed in a Drilling Contractor article from the September/October 2014 issue. For example, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP) has produced guidelines (Reports 501 and 502) on implementing non-technical skills training for well operations. This increased attention was in part due to the implication of failures in drill crews’ cognitive skills in large-scale blowouts such as Macondo and Montara, as well as in the sinking of the large semisubmersible Petrobras P-36. While this is a welcome change of focus, more research is needed to better understand and, consequently, effectively train and assess these vital thinking skills that enhance a driller’s performance.

As part of a three-year PhD project sponsored by Maersk Drilling, this author has been working on identifying drillers’ thinking skills at the Industrial Psychology Research Centre at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, supervised by Professor Rhona Flin. The aim was to identify the specific thinking skills, often referred to as cognitive skills, that drillers need to maintain a high level of awareness of the well state. Then there are the skills needed to apply that knowledge to support drillers’ awareness and decision making through interventions, such as training.

The importance of this research for improving safety and performance has been recognized. Vibeke Sam, Head of Learning at Maersk Drilling, said, “An important part of Maersk Drilling’s strategy is to reach zero incidents on all our drilling units. We believe that understanding the human factor part of our operations and investigating what leads to unsafe behavior can be a vital part to reduce the risks in the hazardous environment. This specific research regarding drillers’ situational awareness is an enabler in the prevention of accidents as it aims to better understand the skills involved in attaining and maintaining situational awareness in the drilling environment. We believe we can utilize the outcome of this research to enhance health, safety and environmental performance.”

What makes a good driller?

The cognitive skill referred to as situation awareness (SA) originated in military aviation: The US Air Force Tactical Combat Command apparently said, “The difference between a good fighter pilot and a dead fighter pilot is situation awareness.” Mica Endsley’s three-level model of SA dominates the field, having been applied in the military, aviation, air traffic control, nuclear power and healthcare. It describes SA as knowing what is going on around you and using that information to predict what is going to happen in the future. This awareness can form the basis of decision making (DM). These skills are essential for drillers to monitor and maintain a mental picture of a well hundreds or thousands of feet below the drill deck by interpreting readings collected from screens and gauges. Yet, surprisingly little research has looked at drillers’ SA.

It can be difficult for experts to describe how they do a task. To identify the key SA skills, cognitive task analysis methods were used, designed to extract implicit expert knowledge. A total of 18 experienced drillers, assistant drillers and toolpushers on a variety of different rigs were interviewed and asked about what they thought made a particularly good driller. They were asked to talk through a challenging day to help the researchers identify the cognitive skills that helped them cope with these task demands. Their responses included being vigilant for changes in drilling parameters, gathering the right information at the right time, keeping a good mental picture of the well state and activities on the rig, sharing information with the crew, and staying a couple of steps ahead of the situation.

Previous research has suggested that the ability to mentally stay ahead of the situation is an indicator of expertise (e.g., this might be called “flying ahead of the plane” or “drilling ahead of the bit”).

Working with drilling experts, many hours were spent watching drill crews take part in simulator-based training at Maersk Training’s high-fidelity drilling simulator in Svendborg, Denmark. The simulator allows crews to train for well control scenarios safely in a realistic and immersive environment. Hundreds of hours were then spent coding behaviors shown in videos taken from the simulator to identify these SA skills.

This meant that the researchers could not only talk to drillers about what a good driller might do, they also could see how they behaved, providing valuable insights. Having used the interview, observation and video analysis data to identify the main cognitive skills associated with drillers’ SA, this was used to develop the prototype Drillers’ Situation Awareness model (DSA, Roberts, Flin & Cleland, 2015). Effectively, this was adapting Ms Endsley’s prominent three-level model of SA for use in the drilling industry.

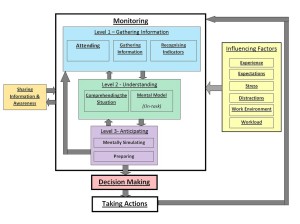

The DSA model shows the key cognitive skills that enable drillers to gather information from the situation (level 1 SA) and build up an understanding of what is happening in the wellbore and surrounding environment (level 2 SA), to predict how this understanding may develop (level 3 SA). It was found that drillers tended to refer to situation awareness as monitoring, as is shown in Figure 2.

The arrows show that these mental processes can affect each other. For example, your mental model (internal “picture” in your head) can direct where you focus your attention (level 1 SA) and what you think might happen next (level 3 SA). The data also highlighted multiple factors that can influence drillers’ SA at both relating to the individual (e.g., experience, expectations and stress) and to the environment level (e.g., distractions, workload and working environment). Working as part of a team, sharing and discussing information, particularly in ambiguous or difficult situations, was also found to influence the driller’s awareness both positively (e.g., help interpreting confusing readings) and negatively (e.g., introducing biases and assumptions).

To see how well the prototype DSA model worked for practical applications, it was applied to a kick detection task (Roberts et al, under review). With help from a drilling consultant and rig manager, the thinking steps, taken from the DSA model, were identified for each technical step in kick detection. For example, change in mud return flow rate is a key positive kick indicator, requiring the driller to attend to the drilling parameters screen and to recognize the change in flow rate (level 1), understand the significance of this as a positive kick indicator (level 2) and anticipate that this could be caused by an influx occurring in the well that may result in a kick or even a blowout (level 3). This would prompt the decision to take the action to flow check. This was useful as it identified the specific SA and DM skills needed for kick detection, which has direct applications for training both experienced and early-career drillers (e.g., as part of well control manuals or training or non-technical skills training), as well as work design recommendations (e.g., software that assists in interpretation of combinations of indicators).

Everything was fine…

Considering the impact that Macondo has had on the oil and gas industry, particularly for highlighting the value of examining non-technical skills, and the relatively limited examination of the crew’s SA in the event, we used the prototype DSA model to try to better understand why the drill crew believed that “everything was fine.” Having produced an account of the negative pressure test from hundreds of pages of investigation reports and court hearing transcripts, the key aspects of the crew’s situation awareness were identified (Roberts, et al, under review).

The analysis provided some indications into why the crew erroneously accepted that the negative pressure test was successful and believed that the well was stable, influencing their decision to continue with the temporary abandonment procedure that culminated in the blowout. The analysis emphasized points already discussed in previous investigation reports, such as the strong expectation that the test would pass early on. It also showed how errors in SA, such as faulty mental models, permeated through subsequent SA cycles, as well as the crew lacking the necessary experience and effective procedures on how to interpret the anomalous negative pressure test readings.

How to train a good driller?

Having developed the evidence-based DSA model, the next objective was to apply the knowledge to develop two complementary performance measures for enhancing drillers’ SA and DM, i.e., helping to support good drillers. This is being done in two ways: a behavioral marker system and a computer-based monitoring task.

Behavioral marker systems are used to evaluate non-technical skills, including SA and DM, by assessing observable behaviors that contribute to performance. These have been used in aviation, healthcare, nuclear power and the merchant navy. The data from the interviews, observations, video analysis and accident analysis were used to identify the key observable skills associated with maintaining awareness of the well and making decisions. This was refined and validated using an expert panel of industrial psychologists and drilling experts, as well as an online survey of drilling personnel.

The system could be used for non-technical skills training, formative assessment and evaluating training effectiveness in simulated, scenario-based training. This has the advantage of being domain-specific and evidence-based. It is worth noting that IOGP will publish guidelines on marker systems (Report 503).

Drilling simulators are good for realistic practice. However, it is not always possible to travel for simulation training. A prototype computer-based Drillers’ Situation Awareness Task (DSAT) has been developed. It measures performance on key SA skills, such as cue recognition speed and accuracy of comprehension of the situation, as well as decision-making responses. The portable assessment tool provides insight into how expert drillers develop SA with the opportunity to give individualized feedback. It also has the potential to look at the effect of influencing factors (e.g., distraction and work design). Laptop simulation training is already in use for well control, but what the DSAT adds is the cognitive data that are collected in the background. This gives the unique advantage to train and assess technical skills (e.g., responding to a new formation), as well as the non-technical skills of SA and DM (e.g. practicing interpreting indicators and taking decisions to flow check).

Answer: enhancing situation awareness and decision making

We know that being a good driller is more than being technically competent. It requires the ability to vigilantly monitor the situation, maintain a high-level awareness of what’s happening in the well so as to understand the significance of an escalating situation and take the right decision at the right time to deal with it appropriately. Using multiple data sets on drillers’ SA and DM skills, two performance measures are being developed.

Our evidence-based behavioral marker system and DSAT have the potential to enhance drillers’ SA and DM through training and assessment so that the industry can train and support not only good drillers but great drillers. And great drillers are safer and more efficient.

Click here to read a human factors article from the September/October 2014 DC.