Competition for rig work ratchets up in Asia Pacific

Facing low demand, additional newbuild deliveries and local content challenges, contractors in Southeast Asia, Australia and India reexamine every segment of the business to identify cost-reduction opportunities

By Alex Endress, Editorial Coordinator

- Although rigs are oversupplied globally, the problem is compounded in Asia Pacific due to its proximity to rig yards that have also become popular stacking locations.

- Australia was already expecting a slowdown in drilling as LNG trains came online, but depth of downturn is putting maintenance and supply infrastructure at risk.

- Industry wins extension to exempt oil and gas industry from Indonesian cabotage law until 31 December 2016.

In the Asia Pacific market, the rig oversupply problem is compounded by the region’s proximity to rig yards in China and Singapore. Not only do a large portion of newbuilds come from these yards, they also serve as popular stacking locations for out-of-work rigs. “It increases the competitiveness of the little demand that is out there,” Ms Teo said.

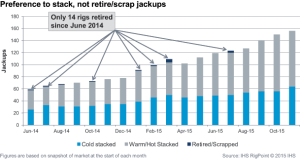

Unfortunately, drilling contractors have few means to correct the situation except to scrap older rigs. This is easier said than done for many drilling contractors, who would rather keep their assets in case the market turns. “They are still hoping for commodity prices to go up,” Andreas Stubsrud, Head of Research at Pareto Securities, said. In the Asia Pacific, where shallow-water drilling remains dominant, it is the jackup market that matters most. It’s also the jackup market that will likely have the largest oversupply of rigs, however. Since coldstacking a jackup can cost just around $5,000/day, it is often preferable for the rig owner to leave the option open for future drilling, Mr Stubsrud said.

Jackup oversupply

While the price of oil shrank by more than 50% in 2015 from 2014 levels, the supply of jackups kept growing. In 2015, 57 jackups were originally targeted for handover to owners, but only 15 units were delivered when the year closed. From 2016-2018, an additional 123 jackups are scheduled to enter the fleet. However, after the market started declining in late 2014, rig owners – contractors and speculators alike – have been mostly deferring deliveries, thus keeping the newbuilds stalled in the Asia Pacific. “Almost all the contractors have said they do not intend to take delivery of these newbuilds unless they have a contract in hand,” Ms Teo said. “I think what we are going to see on a lot of these newbuilds is the deliveries being pushed out until the market improves, if they are not canceled altogether.” The shipyards, for the most part, are working with drilling contractors to hold the rigs until contracts can be found, Ms Teo said. Some contractors have reported that they are being required to pay interim fees to defer the delivery dates, but yards are increasingly keen to work with their customers to avoid cancellations. In one case, she said China-based COSCO Shipyard not only allowed an owner to defer the delivery of a floater by up to 36 months, but it also refunded 5% of the rig’s contract price and deferred it instead until final payment.

Before the downturn set in, peak demand for jackups in 2014 was approximately 420 rigs, according to Pareto. Currently, demand is around 320 rigs and set to decline further over the course of this year. This compares with 490 rigs in the global fleet, with more still on the order book. By 2018, if no additional jackups are retired, supply will exceed demand by almost 200 rigs – even if demand recovers to previous highs, Mr Stubsrud said. Therefore, he emphasized, drilling contractors must start to retire their older rigs. In fact, at least 200 jackups must be decommissioned in order to balance supply and demand by 2018, according to Pareto.

“The good news is that there are 200 old rigs,” Mr Stubsrud said, referring to jackups built before 1990. “The bad news is that no one is scrapping these old rigs today.” He noted that 41 jackups were retired between 2010-2011, the last notable scrapping cycle. It was brought on by the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Currently, 218 rigs in today’s fleet were delivered before 1990. However, because jackups can be coldstacked more economically than floaters, there has been very little attrition in the past 25 years. “It’s very cheap to keep the option alive,” Mr Stubsrud said.

Pareto forecasts it will take at least three more years of low demand for drilling contractors to scrap those 200 jackups. As they remain coldstacked, they will begin to fall into disrepair, and reactivation costs will increase. Many contractors will then likely choose to scrap the rig as they recognize these inevitable costs, Mr Stubsrud said. “It’s just taking a bit of time right now because everyone is still hoping. To take a third off of the market, it’s not that easy,” he said. “You need to have dayrates at or below OPEX levels before those 200 rigs get out of the market.”

Further compounding the oversupply problem is the fact that the bulk of newbuilds are coming from yards located in the Asia Pacific. “Only a handful are not here – that’s all,” Ms Teo said, adding that the higher number of rigs stored in these ports only increases competition. “It is still the first location upon delivery,” she said, so securing work in this region can help to cut down on mobilization costs.

For international drilling contractors, another challenge in Southeast Asia is the increasingly protectionist tendencies of regional petroleum authorities, Ms Teo said. In Indonesia and Brunei, a local content requirement of 35% to 50% is usually targeted in tenders. This can range from employment to rig equipment or office space. Meanwhile, in Malaysia and Vietnam, there is a clear push by petroleum authorities for operators to use local rigs first before they consider “foreign” units. While many of these requirements were in place before the downturn began, low oil prices have only intensified their effects, particularly for foreign companies.

Specific to Indonesia, the long-standing exemption from the Indonesian cabotage law for the oil and gas industry has been extended until 31 December 2016, from when it will be a legal requirement for all vessels engaged in oil and gas activities to be Indonesian-flagged and at least 51% Indonesian-owned. Very few MODUs are presently in this class, said Taf Powell, IADC Executive VP for Policy, Government and Regulatory Affairs, and there are probably no Indonesian units capable of drilling in the conditions seen on the Indonesian continental shelf.

The IADC Southeast Asia Chapter has worked closely with the Indonesian Petroleum Association (IPA) in preparing IPA’s representations to the Indonesian authorities. On behalf of IADC, Mr Powell also sent a letter to the Indonesian government in support of the chapter and IPA, expressing IADC’s reservations on the feasibility of achieving joint ventures in the international rig market to create a viable fleet of 51% Indonesian-owned MODUs.

Under the new exemption, case-by-case applications for relief for foreign-flagged MODUs can be made that are more favorably extended than under previous forms of the exemption. The industry has welcomed the concessions from the government while fully respecting the right of Indonesia to develop an indigenous industry. “Indonesia’s oil and gas sector will be more able to flourish under contracting arrangements that are market-based and impartial,” Mr Powell said.

Equitable negotiations

As the market slump drags on, operators continue to ask for reductions in dayrates on top of improved performance. In some markets, however, dayrates have fallen to levels where maintenance and training can be adversely impacted, Graham Buchan, Business Development Manager for Opus Offshore, warned. “What concerns me nowadays is that some of the dayrates we are seeing are going way below what is actually required to stay in the black whilst operating the rig safely and efficiently,” he said, emphasizing the importance of collaboration amid severe cost pressures. “We must listen to our clients in order to understand what their requirements are. By working together, we can collectively bring a value solution to the table.”

At Opus, the company strives to bring its “fit-for-purpose” philosophy to meet operator needs/demands in the mid-water market. One of Opus’ newbuild Tiger-class drillships, “Tiger 1,” has completed sea trials and is currently in Shanghai. “Tiger 2” shall commence sea trials March/April 2016, and two others are scheduled for delivery – one around Q4 2016 and one around Q2 2017.

These sixth-generation moored drillships carry state-of-the-art equipment as would be expected on any sixth-gen DP vessel. This allows the Tiger drillships to open new markets for midwater drilling, with the capacity to operate in water depths ranging from 300 ft to 5,000 ft and a maximum drilling depth of 32,800 ft. The “Tigers” also feature a variable deck load of 18,000 tons, a mud system that can handle three fluids at a time, offline Christmas tree handling, and an offline stand-building facility.

“A normal deepwater drillship costs $600 million to $700 million to build,” Mr Buchan said. “We’ve managed to build our ‘Tiger’ drillships for much less. This was achieved by having dedicated project managers, engineers, etc, onsite working closely in conjunction with the builders throughout the design and construction periods. In the shipyard, our project teams continue to manage Tigers 2, 3 and 4.” The lower cost allows the contractor to offer Tigers at a realistic dayrate, he said, potentially lowering operators’ OPEX by as much as 50% compared with deepwater drillships.

Whereas dynamically positioned deepwater vessels are routinely used in the higher end of the midwater market and elderly third- and fourth-generation rigs are used between 300 ft and 2,500 ft, Mr Buchan said, Opus sees a potential niche market. “Instead of bringing in a high-cost dynamically positioned ultra-deepwater vessel that cannot operate at the lower depths or an old rig that doesn’t meet modern performance standards, you can bring in our sixth-generation moored vessel, which can cover both bases. Additionally, being a self-propelled mono-hull, transit speed is high, and there is no need for tow vessels,” he said. Target markets for the Tiger rigs include Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, China, Australia, New Zealand, the US Gulf of Mexico and Africa.

Opus also has two semisubmersibles – the “Songa Venus” and “Songa Mercur” –rated for 1,500-ft and 1,200-ft water depths, respectively.

Driven by operator preference, the drilling contractor is also working with oilfield service companies to package its rigs with third-party services, such as cementing, managed pressure drilling, well test packages, mud processing and ROV. “I do believe we, as drilling contractors, are going to see more and more of these initiatives being driven by the clients themselves,” Mr Buchan said. “We are happy to help them in any way we can to achieve a win-win outcome.”

Momentum in Australia

Over the past decade while the market was healthier, significant investments were made to beef up Australia’s rig maintenance, support and equipment infrastructure. However, the region is now at risk of losing these gains, said Luke Smith, General Manager for Easternwell Energy. Mr Smith is also Chairman of the IADC Australasia Chapter. “The downturn could really wind the clock back for us,” he said.

Drilling in Australia began taking off in 2009 when operators started focusing on coal seam gas (coalbed methane) in Queensland. Since then, multinational companies such as Schlumberger, Halliburton and National Oilwell Varco (NOV) have established maintenance and supply centers in Australia. This has helped to cut service-related transportation times by months, according to Mr Smith. “We used to basically have to go to North America to get anything that we needed because Australian oilfield-related suppliers were limited.”

Australia has always been considered a high-cost area, and the region’s oilfield services infrastructure took a while to mature. “We don’t have to go back very far to see what it used to be like when we had nobody here.” From January 2007 to January 2016, the onshore rig fleet in Australia quadrupled, growing to about 50-60 available rigs, according Mr Smith. However, less than 25% of these rigs are currently utilized. Some oilfield service companies have already left, and local drilling contractors are growing concerned that the drop in rig activity will continue to force service companies out, Mr Smith indicated.

One silver lining is that the Australian drilling industry had already been expecting a slowdown in activities, even before the fall in oil prices. “2014 to 2015 was always going to be the point where the ramp-up of drilling activity would finish and a reduced rig fleet would be required,” he said, referencing the completion of several of Australia’s LNG projects. “The drilling would have naturally dropped off because that was the point where LNG trains came online.” Currently, there are six operating LNG developments in Australia, with four additional developments under construction. In 2015, three trains came online from Australia Pacific LNG, Gladstone LNG and Queensland Curtis LNG, which already had one prior train online from 2014. An additional train is expected to begin production for Gladstone LNG in Q2 2016.

For Easternwell, a company with four drilling rigs and 24 workover rigs, the downturn has not drastically reduced its active rig count, Mr Smith said. The company still has two drilling rigs working under ad hoc agreements, in which the operator may hire or cancel the rig at any time without an exact contract term. Easternwell also has 16 workover rigs on contract. These rigs are supporting projects in the Surat Basin, on Barrow Island for the Gorgon Project, and in Brunei. “The maintenance of existing wells must continue because these LNG trains continue to export, so that part of the industry has stayed consistent and possibly even grown, to some extent,” Mr Smith said.

“Our rig count has reduced by around 20%. However, we’ve been affected like everybody else with reduced operating margins,” he remarked. Dayrates have been cut by 10%-40% for drilling and workover rigs alike, he said.

Offshore India

In the offshore Indian market, which so far has been Dynamic Drilling’s main market, the company is focusing on collaborating through long-term contracts and is partnering with operators to further reduce costs. “We are in a market where there is lot of availability on the jackup side”, said Manav Kumar, President & Director of Dynamic Drilling. He is also Chairman of the IADC Southeast Asia Chapter. “Securing contracts for assets and maintaining competitiveness are the key challenges that we face in a low oil price regime and amidst the historically low dayrates,” he said.

Dynamic currently operates six jackups with ONGC, of which three are in cooperation with Paragon Offshore. All but one of these contracts last into 2018, which provides sizable backlog and financial security, Mr Kumar said. He also emphasized that the contract drilling business will not be sustainable in the long term at current dayrates. Dayrates in Indian waters have been brought down by about 40% from peak levels.

To keep pace with the changing environment, Dynamic is examining every segment of the business to improve operational efficiencies. “There is a significant uncertainty toward the length of this downturn and the severity it will lead to. We have to be prepared for a longer term and accordingly position ourselves to take advantage of the next cycle.” Some of the elements being reassessed include cost reduction in consumables, crew hires, logistics, catering and insurance. In addition, Mr Kumar said, his company is assessing costs of planned maintenance for rigs, negotiating prices with shipyards to streamline dry-docking and repairs.

Still, Mr Kumar said he remains optimistic about the future of drilling offshore India due to commitments from the Indian government to ensure domestic energy security. The country currently meets more than 75% of its total energy needs through crude oil imports. However, in March 2015, the government announced a pledge to cut imports by 10% within seven years. This has put more pressure on the NOC to explore new fields while increasing production from existing fields.

“Barely 22% of the country’s sedimentary basins have been explored, and a series of large deepwater blocks remain essentially untouched,” Mr Kumar said. “Although the government has awarded 247 total blocks over the last 13 years, only 16 of the blocks have been developed. Overall, India represents a huge opportunity for offshore drilling contractors like Dynamic.” DC