McKinsey report: Renewables could make up half of global power generation by 2030

By Stephen Whitfield, Associate Editor

Global energy markets are facing an array of uncertainties, including concerns about energy security in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, the long-term transition to low-carbon energy systems continues to see strong momentum and, in some cases, acceleration, according to new research by McKinsey & Company. In its 2022 Global Energy Perspective, the consultancy said it anticipates peak oil demand to come sometime in the coming decade, perhaps as soon as 2024 in the most extreme scenario. Further, the share of renewables in global power generation is expected to reach 50% by 2030 and 80-90% by 2050.

The study cites the regulatory push to hit net-zero emissions targets as a major factor in the energy mix shift. A total of 64 countries, accounting for 89% of global emissions, have made some kind of net-zero announcement, whether through formal legislation, an informal policy document or a general pledge to reach net-zero within a certain timeframe.

On top of that, long-term trends on technology costs have made renewable systems more economically viable. From 2017 to 2021, there was a 50% drop in solar PV technology development costs, a 29% drop in offshore wind technology development costs, and a 42% drop in battery technology costs, according to McKinsey. As a result, 61% of new renewable capacity installation is already priced lower than fossil fuel alternatives.

“We’re continuing to see the economic drivers that allow the energy transition to accelerate,” said Linda Tiemersma, Solution Leader at McKinsey & Company, during a 25 April webinar. “The high subsidies that initially pushed renewables development have also helped push renewables cost down significantly in the last four to five years.”

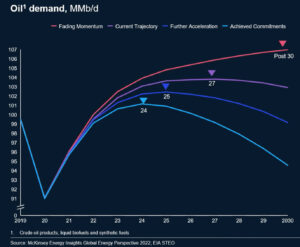

The report asserts that oil demand could reach its peak in the next two to five years, depending on the speed at which countries continue with the energy transition. Oil demand increased by 4.8 million bbl/day year-on-year from 2020 to 2021, and it is expected to reach pre-COVID downturn levels in 2022. Following its current trajectory, oil demand would reach its peak in 2027 before leveling off for the rest of the decade. This scenario would put the world well short of the goal outlined in the 2015 Paris Climate Accord to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2100 – global warming would fall somewhere between 1.9°C and 2.9°C, the report said.

In a “further acceleration” scenario, where the pace of the energy transition increases from its current trajectory but not to the level needed to meet the Paris target (global warming between 1.6°C and 2.4°C by 2100), peak oil would occur in 2025, with demand gradually dropping off through 2030. In its “achieved commitments” scenario (1.4°C to 2.1°C), peak oil comes in 2024 and sees a steep dropoff after that.

Peak oil estimates have moved closer in recent years. The “current trajectory” scenario in McKinsey’s 2018 report had peak oil coming as early as 2037, versus 2027 now. That estimate moved up to 2033 in 2019, then to 2032 in 2020. In last year’s report, the estimate was 2029.

“We’ve gone from a scenario where, before 2018, people were not really talking about peak oil demand, and when we actually tried to forecast that, we weren’t seeing peak oil coming any time in the next 20 years. But as technology has improved, and regulation has gotten tighter, that number is quickly moving forward,” said Christer Tryggestad, Senior Partner at McKinsey & Company.

Still, even with renewables taking up a greater share of the global energy mix, oil and gas will be needed to meet energy demand. In the report’s “further acceleration” scenario, oil consumption will drop by 1.9% from 2021 to 2050, while natural gas consumption will drop by 1.6%. In the scenario, natural gas demand would actually increase by 10% from 2021 to 2030 before reaching its peak by 2035.

“We’re going to see a decline in fossil fuel demand, but investment in the oil and gas sector is going to remain roughly stable,” Ms Tiemersma said. “Maintenance CAPEX for oil and gas projects will remain very high, and exploration spending will increase, though this is partially because of increased environmental requirements for new oil and gas exploration.”

McKinsey’s forecasts did not incorporate any potential long-term impact from the Ukraine war, as it is still too early to assess what that long-term impact may be. However, the company said that the conflict could have a noticeable effect on the energy transition. Europe’s energy system is heavily dependent on imports from Russia – as of last year, the country accounted for 41% of Europe’s natural gas supply, 12% of its coal supply and 11% of its oil liquids supply. With the European Union considering an embargo on Russian oil and gas imports, energy security will become a paramount issue for the region.

Should the conflict, and potential sanctions, continue for a prolonged period, Europe will need to determine how it can substitute its oil and gas supply, said Bram Smeets, Partner at McKinsey. This could mean importing LNG from other locations, boosting domestic oil and gas production or scaling renewable development.

“The future of energy is highly uncertain, and that’s been particularly true over the last few months,” Mr Smeets said. “In several markets, we’re seeing a degree of uncertainty that’s truly unprecedented, even when compared to the uncertainties we saw during the COVID-19 crisis. Every stakeholder will need to closely monitor developments and play through a number of scenarios to make the right decisions.”