Frac fluid disclosures and water testing: Unique state requirements preclude one-size-fits-all strategy

State-to-state inconsistency means operators must seek careful balance between protecting trade secrets and compliance with disclosure regulations

By Lara D. Pringle, Litigation Practice Group and Jones Walker LLP

It’s no secret that, along with the widespread use of hydraulic fracturing in the US, concerns about water quality and potential water contamination have risen among the general public. While available evidence shows that hydraulic fracturing rarely causes contamination of groundwater, state regulators have taken note of public interest in this area and have developed regulatory regimes requiring industry action.

Baseline testing and mandatory fluid disclosures can help the industry to avoid or resolve disputes regarding groundwater contamination and reassure the public that the risk of potential environmental impacts is low. On the downside, state laws and regulations governing hydraulic fracturing vary considerably from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and disclosures may unintentionally reveal proprietary information or trade secrets. To avoid liabilities, oil and gas companies cannot rely on a “greatest common denominator” approach to compliance but must instead create comprehensive, state-specific strategies.

Development of Disclosure Regulations

Although forms of hydraulic fracturing can be identified as early as 1865, the process as we know it today was tested and commercially developed in the late 1940s and was primarily focused on vertical oil wells.

Efforts to adapt hydraulic fracturing technology to shales began in earnest in the early 1980s and were pioneered in the Fort Worth Basin’s Barnett Shale by George Mitchell, through his company, Mitchell Energy.

As the combination of horizontal drilling and improved technologies for hydraulic fracturing made the development of shale plays more profitable, companies began to operate in the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas, the Haynesville Shale in northwestern Louisiana and east Texas, and various other shale plays.

With the development of the Marcellus Shale, activity moved north and east from the Gulf Coast states, into Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York. Many people in these areas of the country were unfamiliar with and distrustful of the industry. Some began to express concerns that hydraulic fracturing, and fracturing fluid in particular, might cause harm to the environment and groundwater.

In 2011, the Groundwater Protection Counsel and the Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission jointly launched a website called FracFocus, where many companies voluntarily posted the composition of fracturing fluid used anywhere in the United States on a well-by-well basis. While FracFocus remains relevant, state-promulgated mandatory disclosure regulations have now been adopted in every state with oil and gas activity.

At the federal level, the US Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management requires the disclosure of fracturing fluid composition for all hydraulic fracturing operations on federal lands.

Additionally, the Environmental Protection Agency created regulations that require manufacturers of fracturing fluid additives to make disclosures under the Toxic Substances Control Act. But given their specific interests in this area, the states have taken the lead in enacting mandatory disclosure regulations specific to hydraulic fracturing.

Mandatory Disclosure: Differences Between States

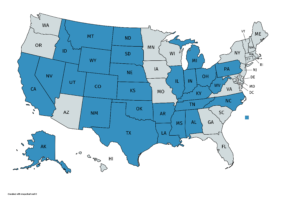

In 2010, Wyoming became the first state to enact mandatory disclosure regulations regarding the composition of fracturing fluid. Arkansas, Pennsylvania and Texas followed suit in 2011. Presently, at least 28 states have enacted mandatory disclosure laws.

Together, these states provide near-universal coverage within the United States, given that almost all oil and gas activity conducted onshore or in state waters is conducted in one of these states.

Not so universal, however, are the states’ disclosure and testing requirements. Driven by a number of factors, such as economic conditions and objectives, and history of the oil and gas industry in the state, each has its own twist on groundwater testing and disclosure regulations. The following illustrate some of the differences from state to state:

In Oklahoma, the operator must submit its disclosures to the FracFocus Chemical Disclosure Registry, or the Oklahoma Commission within 60 days after the conclusion of hydraulic fracturing operations. The disclosure must include the name of the operator, the API number of the well, the location of the well, the date when the fracturing operations began, the volume and type of base fluid, the trade name, supplier and purpose of each chemical and, for each chemical additive, the Chemical Abstract Service number and the maximum concentration.

In Ohio, the operator must disclose the same things that are required in Oklahoma but must also include a description of the geological units encountered, the types of drilling tools used, the name of the person that drilled the well, the elevation and the number of perforations in the casing, and the intervals of the perforations. These disclosures must be filed with the division of oil and gas resources management within 60 days after completion of drilling operations.

North Dakota’s regulation is short and direct, requiring the operator to post on the FracFocus Chemical Disclosure Registry all elements made viewable by the website.

The platforms on which companies must make their disclosures also differ from state to state. While some require the disclosure of fracturing fluid composition to be made to the state oil and gas regulator, as noted above, more than 20 of the 28 regulating states now either require or allow companies to make the mandatory disclosures by posting the information to FracFocus.

Finally, the required timing of disclosures also varies by state. Pre-fracturing disclosure requirements are uncommon, since operators often make adjustments to the composition of fracturing fluid before or during the fracturing operation.

Montana is an exception to this rule; disclosures must be made at least 48 hours prior to beginning well stimulation activities and, upon completion of a well, operators again must disclose the hydraulic fracturing treatments that were utilized.

Most other states demand only that a post-fracturing disclosure of fracturing fluid composition be made, typically between 30 and 60 days after the fracturing is complete.

Here, Texas is an outlier, requiring that a well operator submit the disclosure within 90 days after completion of a well or within 150 days after the date on which the drilling operation is completed, whichever is earlier.

Trade Secret Protection and Challenges

The additives and chemical composition of materials that suppliers or operators use when fracturing a well can be highly confidential. With this in mind, most states have also included in their rules certain protections for trade secrets.

States differ, however, with respect to whether a company must submit information to support the validity of a trade secret claim at the time the claim is made, and its rules regarding who has standing to challenge trade secret claims and under what circumstances. For example, Arkansas, California, Illinois and Wyoming require upfront factual substantiation of trade secret claims.

It can be argued that such upfront, factual justification of trade secret claims will discourage the assertion of illegitimate trade secret claims. Such requirements, however, place additional burdens on companies, consume scarce agency resources in the evaluation of such documentation, and open up the possibility of inadvertent disclosures. Additionally, when the agency possesses such information, there is an increased likelihood of that agency being sued by environmental organizations and other persons seeking disclosure of the information claimed to be a trade secret.

State disclosure laws also differ with respect to how trade secret claims may be challenged. Where a state’s regulations require the disclosure of putative trade secrets to the oil and gas regulator, a person who wishes to challenge a trade secret claim can do so indirectly.

Other states provide more direct mechanisms. For example, while Colorado’s rules do not expressly address trade secret challenges, Colorado regulators have stated that, pursuant to a citizen suit provision in Colorado’s oil and gas laws, a person could challenge a trade secret claim that he or she believes to be erroneous.

Texas and Ohio expressly authorize challenges to trade secret claims by the state’s oil and gas regulator, any other agencies with an interest in the matter, the owner of the land on which the hydraulic fracturing takes place, and the owner of any contiguous land.

Baseline Water Sampling and Contamination Disclosure

The debate over the effects (or lack thereof) of hydraulic fracturing on groundwater continues for many reasons. Contamination can result from a wide variety of natural events and human activities. The presence of contamination, when it does exist, is not always obvious, and the timing of such potential contamination is often uncertain.

Many states, including Alaska, Wyoming, Colorado, Ohio, Kentucky and Pennsylvania, have promulgated regulations to promote baseline testing of groundwater. The rules for such testing typically cover the testing radius from the oil and gas well, the number of water sources that must be tested, whether testing requirements apply to surface water, and so on.

States generally fall into one of three categories:

- Those that do not specifically require any baseline groundwater testing, including Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas. These are typically states with decades of experience and well-established rules regulating fracturing operations;

- States that mandate baseline groundwater testing, including California, Kentucky, North Carolina and Ohio; and

- States that merely create incentives to promote testing, such as Pennsylvania.

One of the ways states promote baseline testing is by creating legal “presumptions” that fall into two categories: evidentiary presumptions and irrebuttable presumptions.

Illinois, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and West Virginia all provide an evidentiary or rebuttable presumption. For example, the Pennsylvania regulations state that if groundwater located within 2,500 ft of the vertical section of an unconventional well becomes contaminated within 12 months after completion or hydraulic fracturing of the well, there is a rebuttable presumption that the oil and gas operations caused the contamination. The oil and gas company must then rebut the presumption by affirmatively proving that something other than its activities caused the contamination, or by showing that the owner of the water supply did not allow the company to sample the water for purposes of pre-drilling baseline testing.

An irrebuttable presumption is a conclusive presumption that cannot be rebutted. Pennsylvania uses an irrebuttable presumption, in addition to a rebuttable presumption, as explained above. While Pennsylvania law does not require operators to perform baseline testing, its law uses irrebuttable presumptions to punish operators for failing to perform voluntary testing.

In straightforward terms, if a Pennsylvania operator chooses not to perform baseline testing and groundwater contamination is subsequently detected, it has no defense against the state’s finding that it is responsible for such contamination.

It is important to note that most states’ testing requirements apply to groundwater and not to surface water. However, regulations in some states, such as California and North Carolina, also cover surface water testing.

Finally, states vary in the degree to which they require that the results of testing be made publicly available. There are concerns that, if test results are made public, this might result in fewer tests being performed, as some landowners may be reluctant to allow testing because they may be concerned about the impact the results may have on their property values. A primary argument to the contrary is that only when results are made publicly available can society address the risk that oil and gas activity will adversely impact groundwater quality.

The state of Illinois grants landowners the option to decide whether test results will be made publicly available, allowing owners of a water well to condition access or permission for sampling under a non-disclosure agreement. On the other hand, Colorado’s regulation provides that testing results must be given to the Director of the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission, which must in turn make the analytical results publicly available.

As we can see, regulations governing hydraulic fracturing are complex and – between states – inconsistent. Operators must review and consider all relevant state laws in order to determine exactly what must be disclosed, whether baseline testing is required, and how to balance their desire to protect trade secrets with the various disclosure regulations applicable to them. DC