Wood Mackenzie: Can the right fiscal terms revive Asia-Pacific’s upstream sector?

According to Wood Mackenzie, Asia-Pacific’s upstream industry has been plagued by declining oil production, exploration and licensing activity. Since 2014, exploration investment in the region has fallen 66% to around $6 billion in 2018, reducing the hopper of new development opportunities.

Recognizing these challenges, governments in the region have begun revising fiscal systems in the hope of reversing the trend.

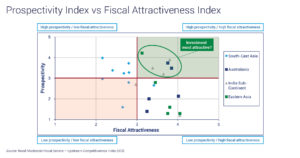

According to Wood Mackenzie’s Upstream Competitiveness Index, Australasia and the Indian subcontinent are the most attractive regions for upstream investment in Asia-Pacific.

“While the main driver in any upstream investment decision is geological prospectivity, balancing that with the right fiscal terms is key to extracting maximum volumes and value,” Nikita Golubchenko, Petroleum Economist at Wood Mackenzie, said. “Looking at fiscal terms and exploration potential in Asia-Pacific, a number of countries in Australasia and the Indian subcontinent fall in the ‘investment attractive’ zone.”

Most countries in Australasia operate concession regimes weighted towards profit-based terms. Such systems are more responsive to possible project cost overruns, mitigating the risk for investors. In some cases, this fiscal structure results in governments not getting the perceived budget revenues from flagship projects.

Notably, Australia is discussing changes to its petroleum resource revenue tax (PRRT) structure, in a bid to ensure fair share of economic rent from resource projects. While the proposals do not affect liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects already in production, assets approaching final investment decision are on the line. The ring-fence limited to offshore projects will significantly reduce the starting tax base for companies that could transfer onshore losses to offshore projects. The revision of gas transfer pricing may also have high material impact, as it forms the price under which PRRT is paid.

In 2016, India replaced its traditional production sharing contract scheme with a pure revenue sharing contract system. As part of the revision, India introduced biddable fiscal terms which allowed potential investors to choose the acceptable level of government share. However, the results of the recent licensing rounds show only incumbent domestic companies’ interest in the blocks.

The lack of international presence proves that the challenge lies beyond fiscal terms, rather with investors’ perception of a basin’s prospectivity and administrative burdens. India’s recently announced reforms for enhancing domestic exploration and production, which include simplifying approval processes and permission for national oil companies (NOCs) to induct private players in their developments, may reverse this trend.

“The mixed response from the industry is mirrored elsewhere in Southeast Asia where there are cost-insensitive fiscal systems, NOC dominance and presence of other regulatory burdens,” Mr Golubchenko said.

The absence of clear decommissioning regulation as a salient feature of fiscal systems may prove a bottleneck, restricting the development of marginal and mature fields. Gas pricing policies too may prove a restrictive cap, deterring investment. Regressive fiscal terms in combination with regulated gas prices can kill project economics.

This year, a number of countries including Bangladesh, Myanmar and Sri Lanka, will be revising their terms in advance of upcoming licensing rounds. Wood Mackenzie expects biddable parameters to be incorporated.

“Driving new investment in mature assets, enhanced recovery, gas infrastructure and deepwater exploration should be the focus of future fiscal change,” Mr Golubchenko said.

“National resource policy and NOCs’ prerogatives in picking the best blocks may exclude international investors, but a more effective collaboration between international oil companies and NOCs is needed to revive Asia-Pacific’s upstream industry,”Mr Golubchenko added.