Case study: Culture of performance drives Iraqi drilling campaign

Best practices document, alignment of multiple teams under turnkey contract help overcome technical, logistical challenges

By Marc-Jan Le Vesconte, Halliburton Project Management; Rob Tinkhof, Shell Projects and Technology; and Paul Hardman, The REACH Group

The giant Majnoon oilfield in Iraq was discovered in 1975 by Braspetro (Petrobras). It is located in southern Iraq, 60 km (37 miles) from Basra. Multiple reservoirs contain an estimated 38 billion bbl of stock tank oil in place (STOIIP), according to the Iraq Ministry of Oil. Following the drilling of 20 wells, operations were suspended in the 1980s due to the Iran-Iraq war. Production resumed after the war, but drilling did not recommence until 2011.

The challenges of Majnoon are many: Unexploded ordinance litters the field; significant lost circulation in the 12 ¼-in. hole; logistics require extensive planning; and all drilling is undertaken by rigs with less experienced crews. The operator’s tendering guidelines required a turnkey arrangement between the operator and the main contractor, leading to an intricate arrangement of sub-contracts. Limited offset data further challenged the drilling process. With different disciplines on the critical path to meet the production target date, associated simultaneous operations led to rescheduling and flexibility on the part of the drilling operations team. Major success factors include a focus on performance; contract management; having the ideal team in place from day one; upfront planning and competence assurance.

This article discusses the drilling program, from the initial contracting strategy through final well delivery. Following an assessment of learnings from the early wells in the sequence, the evolution of the performance culture will be discussed. The working relationship between the operator’s field team and that of the main contractor will be examined, particularly given the turnkey nature of the operation. The realignment of the project objectives after the first three wells will also be addressed.

Background

Majnoon was the first of the major oil and gas fields in Iraq to be offered to international companies for development. The state of Iraq has a 25% stake in the project, Shell holds 45%, and the remaining 30% is held by Petronas.

The field was reported to be producing 45,000 bbl of oil per day (BOPD) in December 2009. The Shell-led consortium aimed to increase production to 8 million BOPD. The Council of Ministers of Iraq approved the contract on 5 January 2010. The initial phase of the contract included the drilling of more than 40 production wells, construction of three gas-separation stations and two refineries, with an overall capacity of 100,000 BOPD.

In Phase 1 of the project (the First Commercial Production, or FCP), the consortium would increase production from 45,000 BOPD to 175,000 BOPD. The plateau production of 1.8 million BOPD is expected to take seven years.

This article deals with the drilling of the initial 15 FCP wells, focusing on the performance improvement process and the way it fit into the overall contracting strategy.

Producing formations

The Majnoon field structure is a double-plunging symmetrical anticline about 60 km long and 15 km wide, with closure in the order of 400 m for the middle and early Cretaceous reservoirs. Fourteen separate hydrocarbon-bearing horizons have been identified in carbonate and clastic reservoirs, including Miocene (Ghar formation), late Cretaceous (Shiranish, Hartha, Saadi, Tanuma and Khasib formations) and early Cretaceous (Mishrif, Ahmadi, Nahr Umr, Shuaiba, Yamama and Zubair formations). The source rocks for the field are thought to be the Middle Jurassic shale of the Sargelu and Naokelekan formations.

Several regional unconformities and shales provide seals for the oil pools, with Nahr Umr shale being a particularly effectively seal horizon for major accumulations at Majnoon and other nearby fields.

Contracting strategy

The requirement of the Southern Oil Co (SOC) was for a turnkey approach to the drilling of the initial 15 FCP wells. The consortium well designs were agreed with SOC and became the basis for the field wells. Since all tubulars, wellheads and associated materials had to be imported, there was little scope to improve the well design during the FCP phase. The turnkey contractor, therefore, bid against the three base well designs – Hartha Producer, Mishrif/ Ahmadi Producer and the Nahr Umr/ Zubair Producer. The Majnoon consortium provided the casing and well design, from which the turnkey contractor took the offset information and developed the drilling program for each well.

The turnkey operation was far from simple. In addition to drilling and completing the 15 wells, with an initial completion date of 31 December 2012, the contractor had to furnish and maintain the field camp, provide the initial road construction, procure the three drilling rigs and all associated services, provide field security and handle the logistics movements. Lead time was less than six months.

To meet this deadline, the turnkey contractor formed an alliance with a major rig contractor under a shared risk and back-to-back contracts. The turnkey contractor was then able to draw on the expertise of its individual product service lines (PSLs) to meet the demands of the compressed time scale. Well timings and well costs were based on limited offset data, which led to misconceptions regarding the drilling and completion time for the FCP wells.

Much of the technical information from the initial 20 wells drilled in Majnoon in the ’80s had been destroyed during the war. Since most of those wells were vertical, translating that limited knowledge into the J-type wells that had been planned on each pad involved assumptions and guesswork. Clearly, there would be a steep learning curve during the initial drilling of the 15 FCP wells, including the massive downhole mud losses associated with the Dammam Limestone.

In addition, the impact of external factors wasn’t fully known or appreciated at the time when the wells were conceived:

• Less experienced rig crews with a lower initial competence level, requiring additional training and personal development;

• Erratic diesel supplies and poor-quality fuel, leading to rig shutdowns and engine problems;

• Licenses of the security providers being revoked or delayed, impacting personnel movements;

• Customs issues at the Kuwait/Iraq border delaying the importation of the third rig into the country and its subsequent start date; and

• Delays to customs clearance for items ranging from drill bits to spare parts for the rigs.

Subsequently, the well sequence had to be rescheduled several times, and the initial delivery date for the 15 FCP wells was put at risk.

Drilling performance

Technical issues affecting the drilling operation and the solutions that were applied is summarized as follows:

• Well azimuth has a profound affect on the problems encountered; the magnitude of losses at the Dammam/UeR and the shale stability through the Zubair;

• Top hole is characterized by flow line blockage due to uncontrolled gumbo. Raising the mud salinity overcomes this;

• Optimizing and controlling ROP in the 16-in. section prevents flow line plugging due to sticky shale formations;

• The 12 ¼-in. section sees formation losses and the potential for hydrocarbon kicks. A combination of controlled drilling, LCM and cement plugs can reduce the losses to acceptable and ensure well control; and

• Changing the well profile through the Zubair (8 ½-in.) from J-shape to S-shape helped eliminate the differential sticking seen on the initial FCP wells. BHA configuration, mud properties and the use of proprietary mud chemicals all contributed to the reduced sticking effect.

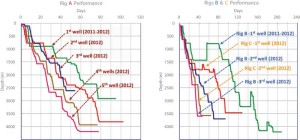

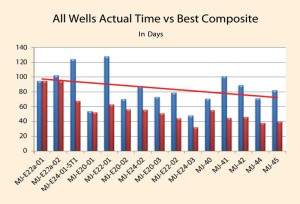

Figure 1 shows the performance improvement seen across the three rigs. Rig A improved by 20% while the other two rigs showed a 25% improvement.

Delivery of the initial wells was challenging due to several factors that were process- and behavior-based. These included mobilization difficulties, downhole difficulties, logistics and resources (human, equipment and fuel). The situation was further complicated by the turnkey relationship between the various contractors, the Majnoon consortium and SOC.

The turnkey contractor is generally recognized for its superior ability to collaborate with customers for performance. When this did not occur as quickly as expected, the company asked its performance consultant partner to assess the drilling implementation to date, make recommendations and organize and create a structured, cultural integration plan and performance process.

The performance consultant’s role was to provide rigor around the way the operational planning was carried out and to facilitate the turnkey team’s learning curve while developing a performance-based culture. In turn, the turnkey team can focus on delivering performance, which is benchmarked against the field-best composite time, a moving goal post, leading to consistency in drilling implementation.

It should be emphasized that the performance consultant’s role was to create a performance culture within the Majnoon turnkey team and not to implement technical solutions. The performance consultant acted as the catalyst for change and facilitated operational planning, learning, metrics and best practices. The contractor’s team provided the solutions to the downhole problems.

Performance optimization

The performance assessment consisted of a series of questions designed to uncover the culture within the organization and to test the processes in place, against what might be considered best in class. Five key success factors were examined: planning; innovation and risk; performance culture; learning; and engagement.

A total of 37 people were interviewed over a two-week period as part of the assessment that was custom-designed for Majnoon. In addition, a benchmarking operation was undertaken to discover the performance gap. At this time, the Majnoon team was on its third well; therefore, the internal benchmarking was rough. While details of the assessment remain confidential to the turnkey contractor, four key recommendations were made:

1. Expedient decision-making. It was clear that the project team was still bonding and coming to terms with the demanding goals of the Majnoon operation. For future projects, the recommendation was made that the team be established at least six months before the spud of the first well (not possible in this case). Operational decisions need to be taken quickly, with the full input of the wider team (operator, PSLs and drilling contractor). It was recognized that the only goal for this project was to safely deliver 15 Majnoon wells by the end of 2012.

2. Team synergy. The relationships across the Majnoon team needed to improve in order to gain from pre-existing knowledge and individual skill sets. In addition, the companymen had to be more inclusive, more active around the rig and serve as the single point of contact for all rig-based activities. Establishing a revised protocol for reporting and input to the Majnoon Consortium eased some of the reactive tasks being undertaken.

3. Proactive vs. reactive. The organization, at the time of the assessment, was seen as extremely reactive, a difficult situation to emerge from and one which consumed the majority of the time available to the team. To become more proactive and focus on planning, the wider project team needed to break the cycle. It was suggested to start with the end in mind and plan backwards from the end of 2012. This gave a clear picture as to the current shortfall in operational time, allowing the team to proactively set targets and goals. In addition, the operational look-ahead was used to efficiently plan personnel and equipment requirements.

4. Creating a performance culture. It has been noted that the project team was reactive. Engaging the wider team on the single target of 15 wells by the end of 2012 enabled a performance focus to be brought into play. Short-term goals were set and success recognized. Performance became the focus for all meetings in the office and at the rig site, without pushing the green crews and impacting safety. It also was recommended that performance coaching be introduced in the office and at the rig site to drive the team to achieve its 2012 goal.

As a result of the assessment, an implementation plan was developed from the four recommendations described above. The performance consultant provided teams of coaches to work among the office and the three rigs. In addition to helping form an effective team, the coach’s role was to introduce the required rigor around the identified key areas: operational planning; after-action reviews; capturing and disseminating learning; sharing best practice; reporting on performance (daily and weekly); and driving best composite performance.

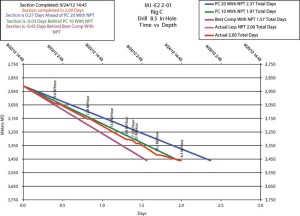

Figures 2 and 3 are examples of the type of performance chart used. The goal was to achieve best composite time or better. As more wells were drilled and completed, the best composite line shifted to the left, making it harder to achieve, leading to more innovative thinking and driving the team to implement best practices. The best composite time across the Majnoon field was decreased by approximately 55% between June 2012 and June 2013 (Figure 3).

In addition to the coaching that was put in place, an operational best practice document was created – the Majnoon Field Drilling Guidelines. The document contained all the learning across the field, detailed the drilling practices to be applied and acted as a repository of field knowledge. However, it is a guideline and does not replace day-to-day decision-making.

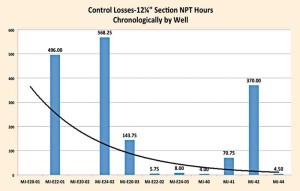

Figure 1 shows the well time reductions on all rigs with each additional well drilled. It is also interesting to look at NPT as a percentage of total well time. While still significant, it generally exhibited a reducing trend as more wells were drilled. However, a more tangible picture of learning can be seen by examining the time spent curing losses in the 12 ¼-in. hole. Although the severity of the losses can, in most cases, be directly linked to the azimuth of the wellbore and, hence, the direction of maximum principal stress, Figure 4 shows a decreasing trend in the time spent curing losses. MJ-42 clearly bucks this trend, primarily as a result of not necessarily applying the best practice and the unfavorable well azimuth.

Throughout the FCP well campaign, 622 lessons were captured specific to the operation and ongoing events. These lessons encompassed a broad base that included drilling activity, completion activity, flat time events, safety-related issues and personnel ideas, all of which enabled the continual improvement to succeed.

Conversely, it is necessary to look back at the project and the performance optimization process in order to identify opportunities that were missed. This particularly applies to the learning that comes from invisible lost time (ILT).

The knowledge that came from the lessons learned was incorporated into the Majnoon Field Drilling Guidelines.

As a result of the performance optimization process implemented throughout the initial phase of the Majnoon Field development, several questions emerged that may lead to continued improvement.

1. Bit design and selection need to be addressed in order to achieve shoe-to-shoe performance where possible.

2. Is the use of the rotary steerable systems feasible? The trial of these tools was inconclusive.

3. Improved QA/QC systems from all contractors must be stressed and demanded.

4. Rigs need to be selected as “fit for purpose” in future campaigns.

5. Understanding the vendor supply/ resupply issues should be further investigated.

6. Well times should be adjusted to recognize losses when drilling the Dammam.

7. Mud programs should be thoroughly reviewed and a new best practice established.

8. Cement programs should be thoroughly reviewed and a new best practice established.

9. Ensure the appropriate level of experienced supervisors is available from all disciplines.

10. Better predict formation pressure to prevent well kicks and excessive losses.

11. Continue to amend and use the Majnoon Field Drilling Guidelines and operational best practices.

Conclusions

Drilling the FCP wells on the Majnoon field represented a steep learning curve for the field consortium and for the turnkey contractor. No two wells were alike in terms of formation behavior, and differences in drilling conditions existed from pad to pad. The lack of detailed offset information created a situation in which the turnkey contractor was forced to continually adjust and adapt. This was made especially difficult due to the somewhat closed nature of the operation and the difficulty with logistics and importation of new tools and equipment. With that said, a significant performance improvement is evident, representing the learning that took place and a willingness of all concerned to work as a team.

The following key factors emerged:

1. The relationship between all stakeholders is critical to the overall success of the project.

2. Flexibility is required:

a. The rescheduling of drilling operations due to material or equipment shortage.

b. The need to fit the drilling operation around pipeline construction and the installation of the production plant at each well pad.

c. The continually changing well conditions.

3. The quality of the fuel for the rigs and camp was a continuing concern. Sufficient spare parts must be available to allow for engine overhaul on location. The cost of such repairs should be built into the contracts.

4. Contract management is key, both from the lead consortium operator to the turnkey contractor and from the turnkey contractor to their vendors and sub-contractors, including the rigs.

5. There is no doubt that the evolution of the team in the field had an impact on performance. A major recommendation is to ensure, where possible, that the ideal team is in place from day one.

6. The addition of the performance consultant added to the competence on the ground and provided a focus for optimization, permitting the turnkey contractor’s personnel to concentrate on well delivery.

7. Aligning the team around a single goal allowed the performance culture to develop and helped break the reactive cycle.

8. Development of the Majnoon Field Drilling Guidelines provided a repository for field knowledge and prevented a number of potential high-NPT events.

IADC/SPE 167949, “The Majnoon Field – A Case Study of Drilling Operations in a Remote Area of Iraq, was presented at the 2014 IADC/SPE Drilling Conference and Exhibition, 4-6 March 2014, Fort Worth, Texas.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their appreciation to both Halliburton and SIPD management for the opportunity to present this paper. In addition, recognition is given to David “Doc” Cowher for his efforts in preparing the data analysis.

References:

1. Shell.com. 2013. The Majnoon Field Development Project, http://www.shell.com/irq/en/projects-business/majnoon.html. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

2. Mirza, A. 2012. Iraq agrees Majnoon oilfield development, http://www.meed.com/sectors/oil-and-gas/oil-upstream/iraq-agrees-majnoon-oilfield-development-plan/3005915.article. MEED. Middle East Business Intelligence since 1957. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

3. Offshore-technology.com. Majnoon Field Iraq, http://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/majnoon-field/. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

4. Shell.com. 2013. Turning a Battlefield into an Oilfield, http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/features-highlights/battlefield-oilfield.html. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

5. Williams, Timothy (2009). Under Tight Security, Iraq Sells Rights to Develop Two Oilfields. The New York Times. 2011-12-09 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/12/world/middleeast/12iraq.html?_r=1. Retrieve 2009-12-11.

6. Iraq Oilfield Development Rights Awarded. BBC News. 2009-12-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8407274.stm. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

7. Hassan Hafidh; James Herron (2009). “Shell Consortium Wins Contract on Iraq’s Majnoon Oil Field.” Wall Street Journal. 2009-12-11. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703522904574589241516916598. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

8. Royal Dutch Shell plc welcomes Iraq Majnoon contract award (press release), Royal Dutch Shell. 2009-12-11.

9. Shell to Boost Iraq Majnoon Oil Output, Eyes Gas. Iraq Business News. 2010-03-30. http://www.iraq-businessnews.com/2010/03/30/shell-to-boost-iraq-majnoon-oil-output-eyes-gas. Retrieve 2013-10-11.

10. Luke Pachymuthu (2010). Iraq’s Majnoon Oilfield to hit 175,000 boed in 2012. Reuters. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2010/03/29/shell-iraq-majnoon-idUKLDE62S02D20100329. 2010-03-29. Retrieve 2013-10-09.

11. Wood Mackenzie. 2011. Asset Analysis – Majnoon, Middle East – MW Arabia – Iraq. December 2011, 1-5.

12. Armenta, M., Tinkhof, R.,Pointing, M.,Cuthbert, A., Ramsawak, S. 2013. Improving Drilling Performance at Majnoon Field. SPE/IADC 166685, 2013 SPE/IADC Middle East Drilling Technology Conference, Dubai, UAE, 7-9 October 2013.

13. Iraq Ministry of Oil-Press Release, 2009. Iraq’s Second Petroleum Licensing Round Majnoon Contract Area – Bidding Results. December 11, 2009, 1-3.

14. Al-Ameri, T.K., Jafar, M.S., Pitman, J. 2011. Hydrocarbon Generation Modeling of the Basrah Oil Fields, Southern Iraq, http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2011/20116alameri/ndx_alameri.pdf. Search and Discovery Article #20116. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

15. Cower, David (2013). End of Campaign Performance Optimization Report. The REACH Group. 2013-09-02.