Industry pursues new strategies to enhance process safety management

By Katherine Scott, editorial coordinator

Until recently, process safety management was primarily seen as something that downstream plants and refineries had to worry about. Whereas they focused on low-frequency, high-consequence events, the emphasis in drilling has usually leaned toward prevention of high-frequency events. With recent industry incidents, however, “it is apparent that low-frequency incidents can have a devastating effect and that the industry now needs to get a better understanding of managing process safety,” Mike Garvin, vice president of HSE for Patterson-UTI Drilling, said in kicking off a panel session at the IADC Health, Safety, Environment and Training Conference and Exhibition on 7 February in Houston. Three speakers, from Transocean, Shell Upstream Americas and Phillip Townsend Associates, offered their perspectives on how process safety management can be successfully applied to today’s drilling industry.

Compliance vs vision

Mike Wright, director of QHSE for Transocean, discussed the difference between compliance and vision when it comes to safety. Compliance is driven by factors such as regulations, HSE cases and policies, whereas vision is driven by variables such as shareholders, customers and safety achievement. Companies can be compliant without achieving their vision (performance-driven), or they can achieve their vision but be non-compliant (value-driven).

However, companies can only get to “excellence” if both compliance and vision are achieved.

At Transocean, efforts to enhance process safety has translated into a focus on operational integrity, defined as “the management of major hazards whereby consistent operational discipline and asset integrity is assured, verified and continuously improved,” Mr Wright said.

The company found that 15 of its 22 operational integrity elements already directly relate to process safety, such as management of change, incident investigation and analysis, and emergency planning and response, then worked to verify those 15 elements by communicating with companies that have robust process safety management systems in place. “It really gave us a good understanding that what we currently have embedded in our management system is something that we can actually pull out and make a whole lot more visible,” Mr Wright explained.

By developing and measuring lagging and leading indicators related to those elements, the company is able to drive a continuous improvement cycle.

“When you get to looking at what is actually embedded in your management systems and you look at what you do and what you don’t do, you may find you have all of the elements for process safety currently existing there. It’s a focus on making it visible,” Mr Wright said.

Importance of mitigations

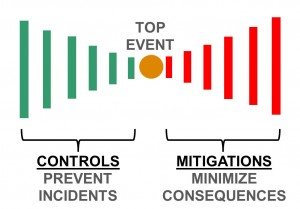

Jeff McPhate, technical safety manager for Shell Upstream Americas, focused on how to keep consequences to a minimum when an incident does happen despite robust prevention measures.

“This is a critical piece of the business that doesn’t get near as much attention as it should,” Mr McPhate said. “As you get better at process safety, as it becomes more unlikely that you’re going to have an event, it gets harder to think about things going wrong and spending the time and effort it takes to make sure that, if they do, (how do) you keep a small incident from turning into a big incident.”

The industry has robust control measures in place to prevent incidents, but once an unexpected “top event” occurs, mitigation measures must kick into gear immediately. Having those mitigations in place and a good understanding of them will go a long way toward minimizing consequences.

Common mitigations include audible alarms, lifeboats, fire detection, ignition control and evacuation routes. “The importance of these is really easy to underestimate … and the truth is none of them are 100% effective in managing a top event.” By having multiple layers of mitigations, companies have “defense in-depth” to greatly reduce the consequences of an event, Mr McPhate said.

“Frankly, people can make mistakes and equipment can fail. That’s not going to change anytime soon, so you have to prepare. As hard as you try to reduce the probability of (incidents), you must prepare,” Mr McPhate said. “With the right mitigations, the consequences can be minimal.”

A different approach to process safety

Vivek Bhatnagar, director for Phillip Townsend Associates, encouraged attendees to see process safety from a new perspective.

“First, process safety is not about safety, and second, process safety is not about any individual company,” Mr Bhatnagar said. “We may have a vague idea about what is it, (but) it’s not about slips, trips and falls.”

To clarify, Mr Bhatnagar went on to define process safety as “a disciplined framework for managing integrity of hazardous operating systems and processes by applying good design principles, engineering, operating and maintenance practices.” He noted that there is no mention of safety in this definition. Does this mean you do not design, engineer, operate or maintain things to be safe? No. Instead, for example, you don’t make something fire retardant or resistant because it’s safer; you do it because — when you deal with flammable materials on a routine basis — it’s just the right thing to do. It is in your very DNA. And there is a huge difference between the two approaches, he said. Safety is no more a goal. It becomes a means to an end.

Recent process-safety incidents have shown that the industry’s current safety indicators “are grossly inadequate for judging overall safety performance,” he said, and improvements are needed in the way we measure process safety. Further, after every major process-safety incident, even if it was caused by just one or two companies, regulators have thrown the rule books at the entire industry, thereby adversely impacting everybody. It is no more about any individual company. Unless, we fight it together, he said, we will continue to fight our own individual battles without being as effective.

Further, the industry is not doing enough to share operational integrity data and lacks a common industrywide language for doing so, Mr Bhatnagar said. He advised the drilling industry to take lessons from the downstream business to develop more safety indicators, as well as a formal platform to share ideas.

“Each and every time there is a conflict and our boisterous and hence more popular ‘let’s get the job done’ mentality triumphs over a more feeble ‘but let’s do it right’ voice, we move a step closer to committing another disaster. Thereafter the question to ask is not if we will have another one but to ask when. It is only a matter of time. So long as we remember this message, we are good,” Mr Bhatnagar concluded.