2018 IADC Chairman to focus on outreach, competency, advocacy

Steven Brady, Ensco, to lead association on efforts to engage policymakers, strengthen training programs and diversify workforce

By Linda Hsieh, Managing Editor

As a child who grew up in a household that moved 20 times in 20 years, you might say that Steven Brady was well-prepared for a drilling career that would take him around the world to places like Aberdeen, Stavanger and even Archangel, Russia. “Frankly, I enjoyed moving. It was the story of my childhood,” he recalled. “I’m sure there are people who like to go to work and do the same thing everyday… but I enjoy seeing new places and new people. New challenges motivate me.”

He also learned from a young age that cyclical businesses like oil and gas don’t need to be feared: His aerospace engineer father worked for years on a project-to-project basis, yet never went for more than two weeks without a job. “All businesses go through cycles. It’s not something to lose faith in,” Mr Brady said. “Things will come back. I fully believe that about this cycle that we’re going through. It’s going to take some time, and it will be a different business when we come out of it, but there will still be good jobs and good opportunities.”

Mr Brady, who now serves as Senior VP – Eastern Hemisphere for Ensco, entered the drilling business in the early ’80s after earning a degree in petroleum engineering from Mississippi State University. He had initially started as an aerospace engineering major, with ambitions for a career in aviation. However, his plans changed after meeting and marrying his wife, Toni, during his sophomore year.

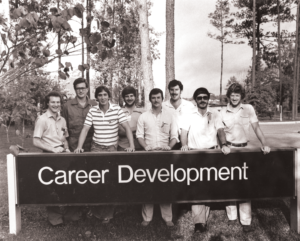

“She quit school to work full time to support us, and I felt it was my responsibility to earn a degree to get a good job, as quickly as I could.” Although the oil business had slowed down significantly by the time Mr Brady graduated in 1982, he was able to land a job with ODECO and was placed into a three-year training program for new graduates.

“It was a tough program. There were about 50 of us that started out, but about half had washed out before we were finished.” The program called for two weeks working offshore in positions of increasing responsibility, beginning as roustabouts or roughnecks, rotated with two weeks of either going to classes or doing engineering work in an office. “Those were three very intensive years, but it was a great start to a drilling career.”

Even during those early days in his career, Mr Brady remembers being interested in deepwater drilling and requesting to be assigned to work on floating rigs. His first semisubmersible was the Ocean Scout in the Gulf of Mexico, which had been equipped to drill in up to 3,000 ft of water – a depth considered to be deepwater at the time. “I enjoyed the complexity and the unique challenges of venturing to greater water depths. Also, it seemed apparent to me that deepwater would be the future of the offshore industry. I could see the business moving farther and farther offshore for greater reserves.”

Around the world with Conoco

Mr Brady was working as a night toolpusher for ODECO when he was recruited for a job with Conoco on Alaska’s North Slope, a place he had never been but was eager to experience. He ended up spending five years there, working in both drilling and production. “It was a great adventure living in Alaska, and I was able to put more of the subjects I studied for my petroleum engineering degree to use during that time.”

By the early 1990s, Mr Brady had moved into Conoco’s international drilling group based in Houston, where he had the opportunity to work on industry-leading deepwater projects in the Gulf of Mexico’s Mississippi and Green Canyon, among others. His next assignment – in Stavanger, Norway – again pushed technical boundaries when he helped to drill a high-risk HPHT well in southern Norwegian waters, followed by a project in the Barents Sea that Mr Brady called a true wildcat. It was located in what was then frontier-territory deepwaters of the Barents Sea. “There was no rig within 500 miles of us,” he recalled.

His experience in the Barents Sea and Alaska led to an assignment to oversee the drilling of an onshore field in far northwestern Russia – a job for which he commuted to from Houston for three years, on a 28-28 basis. His responsibilities included modifying the exploration rigs supplied by Conoco’s Russian partner into more efficient pad drilling rigs that could operate on the Russian tundra. “We modified the existing one-well pads so they could have 10 to 15 wells each, and we modified the rigs so they would crawl along to the next well.” Although these modified rigs were nowhere as sophisticated as today’s pad drilling rigs, Mr Brady’s team was able to reduce the drilling time for each well from six months to 60 days. “I kind of became one of Conoco’s Arctic drilling experts,” he recalled.

Following a couple more years managing Conoco’s drilling group out of Aberdeen, Mr Brady began building his commercial expertise by first leading contracts and procurement for the company’s North Sea business, then overseeing a North Sea field as an asset manager. Notable achievements he made during this time included cutting well costs by half in the Central North Sea, as well as developing contracting methodologies that added $500 million in value to the company. “I was lucky to have worked with really smart and motivated people who taught me about the commercial side of this business.”

Recruited into Ensco

It was in 2002 when Mr Brady was approached by Ensco’s co-founder and then-CEO Carl Thorne, asking him to take the role of General Manager for the company’s North Sea and Africa unit. “It was a hard decision because I was very happy with what I was doing at Conoco and liked the people I was working with… but then it struck me that I was just 42 years old, and it was no time to get comfortable. I had to stretch myself.”

Joining Ensco, Mr Brady found that there was a big learning curve because of different business drivers and constraints between operators and contractors. “Fortunately, Ensco had an excellent group of people who took me under their wings. I learned a lot about being a drilling contractor that I had never learned during those early years with ODECO.”

In the following years, Mr Brady would also move to Dubai to run Ensco’s Middle East and Far East units, move back to Aberdeen during the Pride International acquisition, and then return to Houston to manage booming markets in the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil. “It was a great operation during a great time in our industry.”

In 2014, Mr Brady moved into his current position in London, overseeing Ensco’s Eastern Hemisphere operations – everything from the North Sea to New Zealand. “The thing that stimulates me about this job is that the challenges are never the same, whether it’s something in Nigeria or Angola or Indonesia or another country. I appreciate new challenges and the feeling of accomplishment. It keeps me motivated to strive for extraordinary results. How can we build a better team? How can we work more safely? How do we build a sustainable business in a difficult market? I look at it as never being satisfied and approaching each new opportunity as a challenge.”

Looking at the current state of the industry, Mr Brady said it’s tempting to become negative, but it’s important to forge ahead. “The real key to being a leader is to give people a vision of the future that’s compelling and clear so they can set about striving for it. If you just tell a group of people to get better, you’re unlikely to get much out of them. But if you say to them, let’s be the safest contractor in the world, and here will be the hallmarks of that, you can build their excitement. Then, get out of their way so they can make it happen.”

At the helm of an industry association

One of Mr Brady’s primary goals, as Chairman of IADC in 2018, is to attract a wider group of people into the industry. “We need more young people excited about the business and realize greater diversity of backgrounds and thinking in our business. We need to diversify not only in the US but also on an international basis, and I’m keen to see us go to universities outside the US and set up student chapters,” he said. IADC currently has three student chapters – at Texas A&M University, Missouri University of Science and Technology, and the University of Louisiana-Lafayette – and will be working with additional schools to engage more students in the coming year.

Mr Brady said IADC also must continue to maintain its focus on industry training, through programs such as WellSharp and RigPass. “I remember that as an entry-level person in this business, I looked to IADC for its training materials. We must continue to work on improving the quality of training so that we can improve the competency and safety of our business.”

Another area of effort will be continued engagement with regulators and lawmakers around the world. “For the most part, politicians don’t understand what we do, and their impression of the oil business is what they read in the newspapers. It’s so necessary and beneficial to IADC’s membership to ensure our voice is heard and lawmakers are informed about what the industry is doing.”

Aside from these major pillars of outreach, competency and advocacy, Mr Brady said he’s also eager to provide support to IADC staff and leadership on initiatives that can help the drilling industry to reduce costs and improve performance. The RAPID-S53 BOP reliability database, a joint effort between IADC and the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers, is one example. Modeled on the way the US Federal Aviation Administration collects data from airlines, the BOP database collects data about BOPs with the aim of improving reliability. As of November 2017, the database had already amassed data from more than 4,600 incidents.

“The aviation industry has hundreds of thousands of engines from which they can draw information and analyze for trends, but there aren’t nearly as many subsea BOPs in the world,” Mr Brady said. “RAPID-S53 allows us to see a much bigger data set and to make more intelligent decisions about how we can make improvements. Projects like this are a critical way for the industry to come together – drilling contractors along with operators and service companies – to make the business better and drive out inefficiencies.” DC