Numbers show: Good safety is good business

Investing in workers’ safety and health practices reach beyond costs savings

By Warren Hubler, Helmerich & Payne International Drilling Co; Anthony Zacniewski, Bandera Drilling; Kurt Papenfus, Safety Management Systems; Ryan Hill, Kyla Retzer and George Conway, National Institute For Occupational Safety And Health*

Sound safety practices are, most importantly, critical to ensuring the well-being of employees and their families. This is the paramount motive for operating safely.

However, it also happens that safety makes good business sense. In this article, members of the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) Oil and Gas Extraction Council demonstrate the severe financial impact that on-the-job injuries pose for companies large and small, using real-world case

histories from the drilling industry.

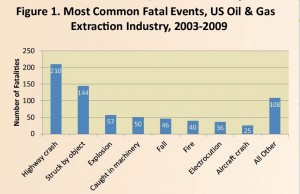

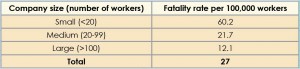

Statistics show that fully half of all oil and gas industry fatalities are the result of either highway crashes or workers struck by objects (Figure 1). Statistics also demonstrate that employees of smaller companies are more likely to suffer fatalities (Table 1). Further, smaller companies are likely to endure proportionately more severe financial impact from serious injuries.

NORA’s purpose in writing this article is to make the business case that sound HSE practices make good business sense, even setting aside the critical human cost. The five cases presented here calculate the direct and indirect financial costs of drilling industry injuries.

The case studies are:

1. Large drilling contractor with high insurance deductible;

2. Lost-time injury (LTI) for small drilling contractor results in zero profit for one month;

3. Mismanagement of injuries may cause injury costs to skyrocket;

4. The financial impact of a death on the worker’s family; and

5. Safety is personal: Beyond dollars and cents, there is a human cost.

The protection of employees from fatal and non-fatal injuries provides the employee and the employer with obvious humanitarian benefits. Protecting employees from injury also provides both parties with financial benefits that are often overlooked or chalked up to the cost of working in the industry.

This article focuses on cost data and example case studies that justify the investment in time, effort and money in protecting personnel from harm.

Cost of occupational injuries

The cost of occupational injuries is often divided into two broad categories: direct costs and indirect costs. Direct costs include payments for expenses associated with the injury or fatality, such as a hospital stay, physicians’ services, rehabilitation, home health care, medical equipment, medical claims, mental health treatment, physical therapy, police/fire/emergency transport, coroner services, burial costs and property damage.

Indirect costs refer to the worker’s lost wages, losses in household production, employer productivity losses, recruiting and training replacements for injured workers, investigation expenses, administrative costs for workers’ compensation programs and damage to the company reputation.

Limited research has been conducted estimating the cost of workplace injuries and fatalities in the oil and gas industry, but one recent study estimated the cost of occupational fatalities by industry. It found that the average cost of a fatality in the US mining industry, which includes oil and gas extraction, from 1992 to 2001 was $1,026,000.

Several tools to calculate the costs of injuries and illness to a company exist, both online and in scientific literature. Additionally, OSHA’s e-tool provides an online calculator to estimate direct and indirect injury costs.

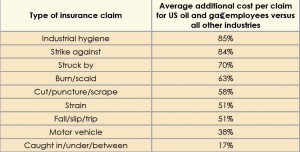

Table 2 compares claims submitted by the oil and gas industry to one insurer. The table compares the average cost per claim for an employee injured in the oil and gas industry versus the cost per claim for an employee injured in all other industries. For the nine primary causes of accidents, injuries to employees in the oil and gas industry are significantly more costly compared with injuries in all other industries combined. The cost per oil and gas claim is as much as 85% higher than similar claims in other industries.

Case study 1: large drilling contractor with high insurance deductible

Warren Hubler, Helmerich & Payne International Drilling Co

Direct cost: According to an analysis of workers compensation insurance loss data of a large US land drilling contractor for the five-year period from 2006 through 2010, the average cost of a disabling LTI or lost-workday case is $200,000 in direct cost to the employer. The average direct cost of an OSHA recordable – medical treatment (RMT) or restricted-workday case (RWC) – is $12,500 per event.

Direct costs include payments for lost wages, surgery and hospital stays for lost-workday cases (LWCs) and medical treatment beyond first aid for injuries like lacerations, broken bones and foreign objects in the eye; dental treatment for chipped and broken teeth; physical therapy; and prescription medications for antibiotics, anti-inflammatories or pain.

Indirect costs: Safety management textbooks suggest the indirect costs are five to seven times greater than the direct costs. Indirect costs include time spent investigating the incident, preparing reports and investigation summaries, time spent communicating the lessons learned, time spent in damage control recovering from the mishap, potential downtime until normal operations resume, cost of screening, hiring, training new employees that may be needed to replace the injured party, damage to reputation, missed future work because of poor safety performance, etc.

Conservatively, using the factor of five times, the average indirect cost of each LWC is $1 million and each OSHA RMT or RWC is $62,500 per incident.

Added together, the total cost of each LWC is $1.2 million, and each OSHA RMT or RWC is $75,000.

One financial metric used by some drilling contractors and business analysts that track them in the financial markets is margins. Margins, or positive cash flow, are simply calculated as revenue minus operating costs. Revenue for a drilling contractor is earned in the form of a dayrate for supplying the rig and the crews needed to carry out the operator’s drilling program or well plan.

Operating costs: Operating costs include labor costs for both hourly and salaried employees, payroll burden for taxes and employee health benefits, materials and supplies and other consumable materials needed to provide drilling services to the operator. If dayrates are $25,000/day in an up market and operating costs are $15,000/day, the drilling contractor’s margin is $10,000/day.

If the rig crew sustains an OSHA RMT or RWC on day one of the project, that rig is making no contribution to the bottom-line profits of the drilling contractor for the next 7.5 days because the margin must now be used to offset the direct and indirect cost of the personal injury.

If the injury severity from the same event is worse – resulting in a LWC – the rig is making no contribution to the bottom-line profits of the company for the next 120 days, or four months.

Down-market conditions: In down-market conditions, dayrates in the US land market may be reduced to $16,000/day. If rig crew wages remain constant, operating costs remain the same at $15,000/day. The margin is therefore reduced to $1,000/day.

Total costs: The same injuries described above would now take 75 and 1,200 days (or nearly three or more years), respectively, to cover the total cost of one OSHA recordable or LTI.

This example is for a drilling contractor with a high insurance deductible. Companies with lesser deductible rates may see less in direct costs of each claim as the insurance provider is expected to cover the direct costs as part of the insurance coverage. However, the indirect costs will still negatively impact the employer (not the insurance provider) and eat away at profits.

Companies should consider: How many rigs can it operate at $0 profit margin because of work-related injuries and still remain a viable business entity? How can this case be applied into its business terms to demonstrate that accident and injury prevention is a worthwhile investment?

Case Study 2: Lost-time injury for small drilling contractor results in zero profit for one month

Anthony Zacniewski, Bandera Drilling

A worker employed by a smaller US land drilling contractor suffered a LTI that resulted in the partial amputation of the worker’s thumb. The injury required surgery and a recovery period of 14 days before the employee was cleared to return to work for light duty. The employee was able to return to his normal work duties after 94 days. This case study describes the costs associated with this LTI; a common and relatively minor injury in the oil and gas industry.

Direct cost: Direct costs include compensation claims, which cover medical costs and indemnity payments for an injured or ill worker. According to the employer in this case, the direct cost of this LTI was $24,000. This included both the cost of lost wages paid to the employee and the cost of medical care to treat the injury.

Indirect cost: Indirect costs include expenses such as the costs to train and compensate a replacement worker, repair damaged property, investigate the accident and implement corrective action, maintain insurance coverage, costs related to schedule delays and added administrative time. Estimates on the relationship between direct and indirect costs vary widely. To estimate the indirect costs associated with this case, the authors multiplied the direct cost by a factor of five: $24,000 x 5 = $120,000 total indirect costs.

Total cost: The total cost of this injury is the sum of the direct and indirect costs: $144,000.

Bottom line: As discussed in the previous case study, one financial metric used by drilling contractors is margins. The drilling contractor in this case study had a per-rig margin of $5,000/day. Because the LTI resulted in 94 days of lost productivity from that worker and $144,000 in total costs, that rig made no contribution to the bottom-line profits of the drilling contractor for the next month because the margin was used to offset the direct and indirect costs of the injury.

Case study 3: Mismanagement of injuries may cause injury costs to skyrocket

Dr Kurt Papenfus, Medical Director for Safety Management Systems

The injury and severity: This case study also involves a hand injury but with different results, impacts and conclusions. A rig worker employed by a large drilling company and working for a major oil company was poked through the glove by a broken wire in a steel cable that had grease, mud and other contaminants on its surface. This “wicker stick” led to a staph infection.

Delayed examination and treatment: As is often the case, the employee did not stop working, clean the wound or hands and did not report the injury until his third day off-duty and away from the rig. He then went to the emergency room with severe pain and swelling, thinking he had broken a finger.

On examination, a puncture wound was discovered under his wedding band on his left ring finger. The ring was removed, and the wound was cleaned. An infection was diagnosed, and the patient was placed on IV antibiotics. Despite the IV medical treatment, the employee experienced an increase in pain and swelling in the finger and hand in the next few days.

Eight days after the injury, the hand surgeon offered relief by surgically operating on the infected hand by opening, draining and further cleansing the wound. The surgical incision ran the length of the finger, through the palm of the hand and down to the wrist. The incision remained open and irrigated for three days. The employee’s hand healed with some stiffness. After 18 days, the employee was released to restricted duty for six weeks.

This case could have cost much less than it did for the drilling contractor, their insurance provider and the employee had it been reported and treated in a more timely manner. The direct cost to the drilling contractor was about $80,000. The indirect cost is estimated at an additional $400,000.

It should be noted that the LTI had the potential to also result in the loss of the remainder of the rig contract, valued at about $16 million in revenues.

Effective case management is critical to preventing workplace injuries from requiring hospitalization, reaching the LTI classification and containing medical costs. The utilization of safety/medics in remote operating areas is a proven benefit in ensuring timely treatment, mitigating injury severity and containing medical costs. Simply put, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” or “Pay now or pay more later.”

Case Study 4: Financial impact of a fatality on the worker’s family

Ryan Hill and Kyla Retzer, NIOSH

There are a number of tools and methods for estimating the economic impact of work-related injuries to the employer, worker and society. However, most of these methods fail to describe the financial impact of a fatality on the worker’s family. This case study estimates the financial impact to the family of a 25-year-old oil and gas worker, husband and father who died as a result of injuries sustained on the job.

This example is based on the true story of a worker who was driving a company pickup, drifted off the road, rolled the vehicle and was killed after being ejected. He was not wearing a seat belt while operating a motor vehicle.

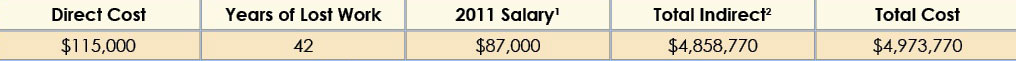

The direct cost used in this example was a single value ($115,000), which was derived from the direct costs associated with a similar event that occurred to the employee of a large US drilling contractor in 2011. The lost future earnings of the injured worker, or indirect cost, was calculated by subtracting the age at death (25 years) from the average retirement age (67 years), and multiplying that number (42) by the worker’s annual salary (Table 3). To account for increased wages over time, the authors included annual salary increases that follow the consumer price index.

This case study estimates that this death resulted in the loss of approximately $5 million to the worker’s family, primarily from lost future income. Effective HSE programs help lead to fewer fatalities, resulting in increased productivity, a reduction in lost income and a more positive image for the oil and gas industry.

Case study 5: Safety is personal – beyond dollars and cents, there is a human cost

Anthony Zacniewski, Bandera Drilling

All injuries that occur in the workplace that require medical attention have a direct and indirect price. The injuries can be a medical treatment only, RWC or LTI. This price can be a smaller amount or can run into hundreds of thousands, and in some cases millions, of dollars. The company will somehow absorb these costs or go out of business.

Human costs: The cost of an RWC, LTI and fatality can and usually does reach staggering amounts. A small company will not only incur the financial impact of the injury but also the personal impact. Most small companies employ many immediate and extended family members and close friends. Some may be brothers, cousins, uncles and so on. When an injury or fatality occurs, it is felt by all in the workplace family.

The dollar amount that is paid is too often the focus of why safety is so important. Injuries come at a price, and sometimes that price is high. The effect often overlooked is the price paid by the injured person and his/her family. Everyone has seen roughnecks with missing fingers, most displaying the fact with pride. They act normal. However, the loss of a finger or thumb means you have to learn many things over: how to write, button a shirt, unzip a zipper, etc.

Most injured workers will not let anyone know how devastating the injury was to them, but it does affect them. Imagine a hunter who has lost his trigger finger or a fisherman unable to cast his lure or crank his fishing reel.

A major back injury sometimes takes several surgeries to fix. More times than not, the damage cannot be fully repaired. The injured worker will often live in chronic pain and can no longer do many of the things that he used to do: pick up the kids, ride in a pickup down a dirt road and sleep normally. This takes a major toll not only on the employee and his ability to make a living but his family as well.

A fatality: There is no way to completely determine the monetary value of a life or the financial impact a fatality has on a company or the family involved. The costs associated with a workplace death can and have put many small companies out of business.

Beyond the company, think about the family. A mother and father have lost their son. A man or a woman has lost a spouse – their means of financial and emotional support. Children have lost their parent, their mentor and coach. These losses can never be replaced, nor can the family ever be adequately compensated.

The monetary costs to the employer may be overcome, but the effects on the injured person and their immediate family lasts forever.

Conclusion

A strong investment in time, effort and money is required to prevent harm to workers, protect their immediate families from financial devastation and improve the industry’s safety performance and image. Failure to support such investment has a significant impact on the industry’s most important asset – its people, who give their time, effort and sometimes their lives in support of extracting the natural resources needed to fuel improvement in our economy and maintain our way of life.

Sound safety and health practices, along with a comprehensive claims management and return-to-work processes, are paramount to reduce injury severity, to prevent deaths and to achieve continued safety performance improvement across the oil and gas industry. Whether to employer or employee, safety is good business and a worthwhile investment.

Go to OSHA’s online calculator to estimate direct and indirect injury costs here.

This research was conducted with restricted access to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the BLS.