Open-hole completion innovations push efficiencies in shales

Longer laterals, rising stage counts drive uptake of open-hole systems in areas like Bakken, Granite Wash

By Katie Mazerov, Contributing Editor

Designing an unconventional well these days is anything but simple. A decade of learning has uncovered a multitude of issues for operators to consider, from reservoir characteristics to stage counts. Thanks to fast-evolving technological advances, operators also have multiple options. Cemented plug-and-perforation or an open-hole completion using ball-activated sleeves? Composite plugs or packers? Or, a hybrid approach that combines the best of both worlds?

Designing an unconventional well these days is anything but simple. A decade of learning has uncovered a multitude of issues for operators to consider, from reservoir characteristics to stage counts. Thanks to fast-evolving technological advances, operators also have multiple options. Cemented plug-and-perforation or an open-hole completion using ball-activated sleeves? Composite plugs or packers? Or, a hybrid approach that combines the best of both worlds?

While cemented plug-and-perforation (P&P), which uses bridge plugs on wireline for isolation, remains by far the No. 1 completion technology worldwide for multistage stimulation, open-hole completions have advanced at a fast pace over the past five years. This trend has been driven by longer laterals and the need for more stages. Ball- drop/sleeve fracturing techniques have improved significantly, breaking through the early threshold of 10 or 15 stages to provide hydraulic fracturing capabilities for 50 or more stages with increased efficiency and reliability. Degradable alloys have further improved efficiency, the latest trend being a dissolvable P&P system that can be applied in open holes.

“Operators in every major unconventional play are actively using, have tried or are considering some form of open-hole completion,” Beau Wright, Applications Engineering Manager for Baker Hughes, said. “Some areas use the technique more than others, and we’ve seen shifts back and forth between P&P and open-hole methods. One system is not technically superior to the other, and these plays are not static environments.”

Areas where open-hole systems are more common include the Bakken and Three Forks in North Dakota, the Granite Wash and Mississippi Lime. “Added efficiency for the longer laterals is a key driver, but in some cases, the choice is as simple as operator preference or familiarity and comfort with one system or the other in a given formation,” Mr Wright said.

The need for efficiency is especially important in a market constrained by lower oil prices. “We are now in an economic environment where commodity prices have dropped so low that the fringe regions of every play are uneconomic, regardless of how efficient we are,” John Cadenhead, Strategy Manager, Unconventional Resources for Schlumberger, said. “Operators can’t drill new wells that will pay out over time, so they are selectively targeting core areas, or sweet spots, to reduce well costs and improve economics. The challenge is to maintain the efficiencies we have gained over time.”

Acknowledging that 30-40% of an unconventional well does not significantly contribute to production, Mr Cadenhead said operators more than ever must focus on the reservoirs they understand and the stages they know will produce, eliminating the stages that won’t produce. “If we can reduce well completion costs by 30%, a well on the outside of the sweet spot becomes productive even at these low oil and gas prices.”

The convergence of enhanced reservoir understanding – where to stimulate and why – and continued technological advances to overcome the mechanical limitations of stimulating longer laterals is the key to optimizing efficiency, suggests Isaac Aviles, Global Portfolio Manager, Multistage Stimulation for Schlumberger. “The challenge we face is that the reservoir is driving longer and longer laterals with more stages per foot.” Nowhere is this phenomenon more evident than in the Bakken, where laterals are now 10,000 ft or longer. The play has been pivotal to the evolution of open-hole completion technology.

Overcoming limitations

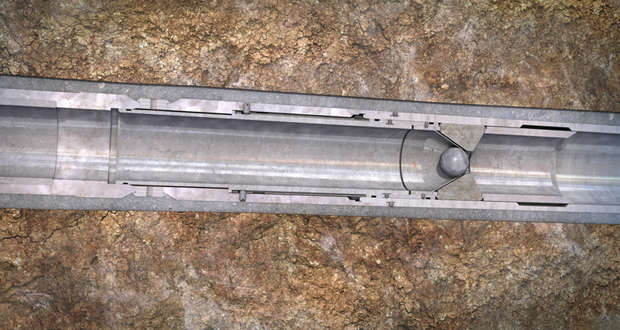

Open-hole completions technology relies on a graduated ball solution, with the smallest ball at the toe and largest at the heel, with open-hole packers for isolation. “The casing size physically restricts the number of balls we can launch and the number of stages we can fracture,” Mr Aviles explained. “When the ball reaches a certain size, the drift of the casing will limit the completion.” Alternatives include repeater systems that use the same ball sizes, or hybrid systems that use a combination of ball-drop technology in the deepest section of the well and the P&P technique once the casing limitation is reached.

A challenge has centered on the risk of balls becoming stuck in the well and the need for intervention and milling operations post-fracturing, Mr Aviles explained. This led to the development of degradable solutions, now commonly used in unconventional wells. In late 2013, Schlumberger introduced a degradable fracture ball for open-hole, multistage stimulations. The aluminum-based alloy enables fracture balls to completely degrade within days.

Although for many years, the majority of completions in the Bakken have been open-hole sliding sleeve systems, P&P has become a widely used completion method in the play. “As a way to reach the desired stage count, operators may develop their wells using P&P methodology, with open-hole packers for isolation,” Mr Aviles said. “A caveat is that, contrary to ball-drop systems, P&P completions require mechanical intervention to remove the plugs and start production. This may increase the completion complexity in long horizontal wells with high stage counts.”

Further, in the Bakken, the industry is seeing an uptake in cemented P&P completions, a trend driven by the need for greater flexibility in increasingly longer laterals, with clusters placed close together.

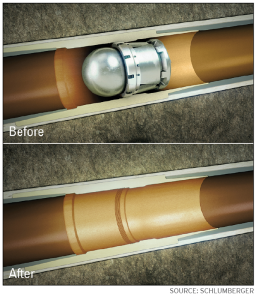

In response to that shift, Schlumberger in February introduced the Infinity dissolvable plug-and-perf system, which uses degradable fracturing balls and seats, instead of plugs, to isolate zones during stimulation in cemented and open-hole completions. The system initially launched in the Eagle Ford, although installations have been done in most of the major shale plays. It enables an unlimited number of stage counts and eliminates the risks and cost associated with mechanical intervention, such as coiled tubing.

“The balls and seats, which are compatible with most fracturing fluids and acid flushes, completely dissolve in common completion fluids, enabling the well to immediately be put on production,” Mr Aviles said. “Infinity uses the same setting tools and gun strings deployed with conventional P&P systems, so customers see a seamless transition.” The technology also can be integrated with other methods, including conventional ball-drop systems, for hybrid operations.

Economics, formation characteristics

Determining whether to complete a well using an open-hole ball-drop systems or a cemented P&P ultimately depends on economics, the characteristics of the reservoir and size of the stimulation. In western Canada, open-hole completions have been used for at least a decade in the tight oil and gas sands of the Montney, Cardium and Viking formations. Production began from vertical wells in these plays more than 50 years ago.

“These formations lend themselves to open-hole methods versus cemented P&P completions, because they have good permeability and porosity and don’t require huge fracture stimulations,” explained Tim Wood, Drilling Manager for Trilogy Energy, headquartered in Calgary. “The economics of this approach are better than using cemented liners with P&P. While these plays could still be produced vertically, it is more capital-efficient to drill one well across a section and complete it using ball-actuated sliding sleeves.”

Open-hole completion technology in this region is different than it is in the US. “In this case, we’re applying unconventional technology in conventional reservoirs,” Mr Wood said. “We’re doing multistage completions, but the fracturing jobs are much smaller. Instead of 100 tons of sand and 6,000 bbl of water per stage, we’re using 10 tons of sand and 100 bbl of water per stage.”

Trilogy began using open-hole ball-drop completions in the Montney in 2005 while shifting from vertical to horizontal wells, where the laterals are now extending to two miles. The play produces light crude oil with associated gas and liquids-rich natural gas. Stages are typically 100 m (328 ft) apart for gas wells and 75 m (246 ft) for oil wells, resulting in 32-42 stages for a two-mile lateral.

The company has expanded into the Gething formation, drilling three wells last year and planning one this year. “The Gething reacts more like a traditional sandstone formation, with initial production rates not as high as shale wells but drop-off rates also lower,” Mr Wood said. The Montney, however, is more shale-like and exhibits higher IP and drop-off rates.

Unlike the US shale plays, the limitations of ball-drop systems don’t pose a significant problem in the Canadian formations. “Because we are in more traditional formations, we are not pumping the high-rate fracture jobs, and the graduated ball sizes don’t restrict our operations like they do in areas that use the larger, high-rate stimulations. We can use gelled fluids and achieve reasonable fractures using fairly small ball sizes.”

Last year, Trilogy moved into the Duvernay formation, completing six wells using cemented P&P completions rather than the open-hole ball-drop method. The play’s shale wells have been compared with those in the Eagle Ford. “Using cemented P&P completions, we are achieving better predictability with our stimulations, pumping the fracture treatments without sand-offs,” Mr Wood said.

Compartmentalizing the lateral

Whereas a true open-hole completion is defined as one in which the entire lateral is completed and produced without any casing, operators drilling horizontal wells in tight reservoirs years ago realized that additional mechanical segmentation and isolation of the lateral sections, along with multistage techniques, was necessary to improve the effectiveness of stimulation treatments and production profiles, explained Andrew Eis, Senior Product Champion, RapidSuite Frac Sleeve Systems for Halliburton. “This paved the way for the improved open-hole completions technologies we know today, with the capability now to ultra-compartmentalize the lateral.

“Reservoirs with competent rock and a high number of exploitable natural fractures are good candidates for open-hole completions as they enable the use of open-hole packers to achieve zonal isolation while keeping the majority of the formation along the lateral available for stimulation and production,” Mr Eis said. “The progression of open-hole packer and, specifically, ball-drop sleeve technologies, have been substantial in effectively enabling more fracturing stages, covering more of the lateral with tighter spacing and addressing wellbore cleanout concerns in extended-reach environments.” He added that promising new technologies have the potential to reverse a trend of cement isolation that has resurged in some plays as operators look to improve production and reduce costs.

“One of the biggest advances is the trending application of enhanced open-hole sliding sleeve technologies in cemented wellbores, which gives customers more options in wellbore construction and completion systems,” he said. Halliburton’s full-bore CT shiftable-sleeve systems enable deployment of an unlimited number of cemented frac sleeves. The more operationally efficient and lower-risk ball-drop systems can also be reliably cemented with improved wiping systems and methods.

Open-hole packers and ball-drop sliding sleeves can reduce cost per barrel of oil equivalent (BOE) through stimulation efficiency and effectiveness. “By dropping the ball for the next frac sleeve immediately following treatment, over-displacement and water usage can be minimized,” Mr Eis explained. “The use of dissolving balls eliminates the need for wellbore cleanout and improves initial production.” For one operator in northern Mexico, Halliburton designed a “zipper-frac” completion of two wells using open-hole ball-drop sleeves to achieve an 85% reduction in stimulation time and 50% reduction in water usage. Operational risk was reduced by eliminating wireline. Combined initial production of the wells was 8,320 bbl/day, more than 10 times the play average.

“In today’s suppressed oil price market, many customers are doing everything they can to boost production for cash flow, while cutting costs,” he continued. “On a four-well pad in the Bakken, it can take an average of three extra days to bring the pad online using simultaneous wireline and frac operations with P&P versus ball-drop sleeves. That can equate to $160,000/day in lost production for four wells averaging 800 bbl/day initial production.”

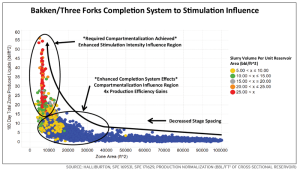

Halliburton’s recent R&D efforts have focused on the integration of stimulation and completion systems technologies for open-hole designs. The 50+ RapidStage ball-drop sleeve system, introduced in 2014, enables a high degree of reservoir compartmentalization. It is being used with AccessFrac multi-cycle stimulation, which provides a new method of fracture isolation using a diversion technology that enables the placement of multiple proppant cycles over each zone.

“With this integration, also launched in 2014, we are essentially doubling the number of effective fractures per zone, improving stimulation compartmentalization by 100% over conventional methods,” Mr Eis said. “This is a valuable tool when trying to reduce costs and improve fracture quality and production output. We don’t need 100 stages to achieve ultra-compartmentalization.”

The multi-cycle approach also mitigates “well bashing,” or interference that often occurs in infill pad completions, especially with lower-viscosity tuned designs.

A common fracturing challenge in the open-hole environment is poor fracture initiation, which can rob critical net pressures in the fracture and increase fluid loss near the wellbore. This increases surface pressure requirements and inhibits the size and complexity of the fracture network. Halliburton is investigating methods to reduce near-wellbore excessive pressures and injection restrictions.

“By tuning a fluid system and fracturing process to overcome persistent near-wellbore losses, net pressure in the fracture can be optimized to provide a large hydraulically connected fracture network with improved flow capacity near the wellbore,” explained Matthew Lahman, Product Champion for Halliburton Production Enhancement.

Reducing the cost

Weatherford has enhanced its SingleShot stimulation sleeve suite with a maximized frac ball-and-seat system that enables operators to stimulate up to 60 open-hole well stages, including the toe sleeve, in a single 4 ½-in. liner job. Introduced mid-2014, the MXZ system for 4 ½-in. completions has been deployed in more than 50 wells, with many customers choosing the system over conventional, cemented P&P methods to save time, explained Justin Vinson, Product Line Manager, ZoneSelect, for Weatherford. The sleeves containing graduated ball seats are activated using matching composite balls or metallic dissolvable balls. Annular swellable packers, installed as an integral part of the casing string, provide zonal isolation.

“In the unconventional plays, operators initially opted to design cemented completions, using the more common P&P method, because they could reduce costs by not investing in open-hole isolation,” Mr Vinson said. “However, customers concerned by the large consumption of water, handling explosives onsite and prolonged operating time have started switching from P&P to open-hole completions. The newly launched SingleShot sleeves with MXZ seat system enable more zones to be treated, which is a priority for operators as they are increasingly segmenting the lateral into smaller, more numerous stages in order to fracture more of the reservoir.”

A key benefit of using sleeves instead of P&P is the time savings, he noted. “It takes 15 minutes or less to pump the frac ball down, compared to 45 minutes to pump a composite plug downhole and even longer to mill it out. The entire completion job takes two to three days, whereas with P&P, we have to pump in the composite plug, set it, perforate, then pull all the equipment out of the hole, fracture the zone and start the process over again.”

The new seat system provides continuous isolation within the sleeve, enabling the ports to be opened quickly for stimulation. The rupture disk toe sleeve establishes initial communication with the reservoir after a pressure test is completed, with no intervention required, he explained. The toe sleeve can be used to fracture the first stage and pump down the first frac ball.

The technique, which is not reservoir-dependent, is being used worldwide. An operator moving from a 35-40-stage open-hole completion design to more than 50 stages in a 10,000-ft lateral in the Three Forks Reservoir in North Dakota chose the new ball-and-seat system, saving more than $2 million over a conventional cemented P&P system for the job, according to Weatherford. Swellable packers eliminated the need to pump cement. The system also can be used to stimulate up to 32 stages in cemented completions and can be customized to use with other equipment in the Weatherford fracturing completion system to achieve the desired pressure rating and number of zones.

For wells where the stage count exceeds 60, Weatherford offers a hybrid system to enable the SingleShot sleeves to run in tandem with the i-ball sleeve, which uses a one-size ball, rather than graduated-size balls, to open sleeves. “There are virtually no limits to the stages of i-ball, which can be added to increase the number of zones of the SingleShot system,” Mr Vinson explained. “With more i-ball sleeves, the minimum seat ID gets larger, and there is no need to mill out the seats.”

Fast-moving pipeline

In recent years, Baker Hughes’ open-hole completions offering has been one of the fastest growing in terms of new tool development and perpetual improvement, as more customers recognize the benefits, such as reduced completion times, of the approach over P&P methods, Mr Wright noted. “With P&P, CT and wireline have to be rigged up and down between each stage, and the plugs have to be milled out before production can begin. With the sliding sleeve method, each sleeve can be shifted open to begin a new stage without having to shut down the pumps or rig up/down services, and production can be turned on as soon as fracturing is completed.”

Maximizing the stage count has been a driver for innovation. In late 2014, Baker Hughes introduced a new version of the company’s FracPoint ball-activated system, featuring an optimized ball and ball seat interface that enables up to 54 stages in a well. “This new system leverages our disintegrating frac balls, which, compared to traditional composite balls, are stronger and can achieve a greater differential pressure for a given ball and seat,” Mr Wright said. “The geometry of the tool provides just enough of an edge on the ball seat to hold the ball and still achieve the differential pressure rating to accommodate more ball sizes downhole and, thus, fracture more stages.” The balls disintegrate after stimulation once in contact with produced water or completion brines to ensure an obstructed flow path for hydrocarbons, without the need for through-tubing intervention after fracturing.

The company also has developed a cemented MultiPoint (MP) FracPoint system as an alternative to using packers for isolation in open-hole wells. In this case, the sleeves are cemented in place to provide stage isolation. Introduced in mid-2014, the enhanced MP system uses one ball to open and fracture through as many as five sleeves per stage.

“The technology maintains the benefits of an open-hole system but mimics one of the most desirable features of P&P, which enables perforation through clusters rather than a single entry point,” Mr Wright said. “While a single entry point can distribute treatment relatively evenly, in some cases operators end up with preferential flow into specific sections of a stage, rather than an even treatment. By using multiple sleeves and entry points per stage, the system helps to more effectively distribute the fracture treatment across a given interval.”

Baker Hughes is using these systems in most US unconventional plays, as well as in parts of the Middle East, North Africa, China and sections of the North Sea and South America, where operators are exploring new open-hole techniques for conventional and unconventional development, Mr Wright said.

Infinity is a mark of Schlumberger. RapidSuite, RapidStage and AccessFrac are registered trademarks of Halliburton. ZoneSelect, SingleShot and i-ball are trademarked terms of Weatherford. FracPoint is a trademarked terms of Baker Hughes.